Introduction

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically set back progress on sustainable development. From a financing for development perspective, countries are faced with a dual setback – they have regressed on sustainable development outcomes, and they have much less fiscal space post-pandemic to invest in recovery and the SDGs. As they formulate recovery plans to ‘build back better’, it is thus imperative that such strategies include a coherent and integrated approach to financing related investments.

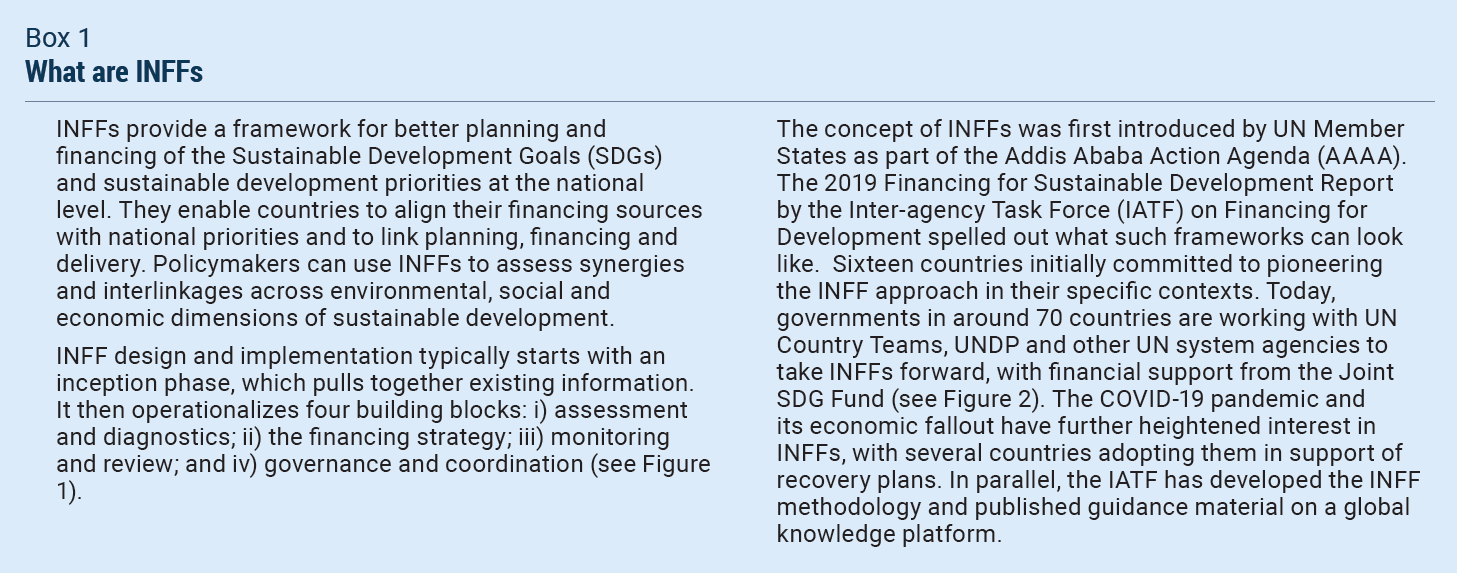

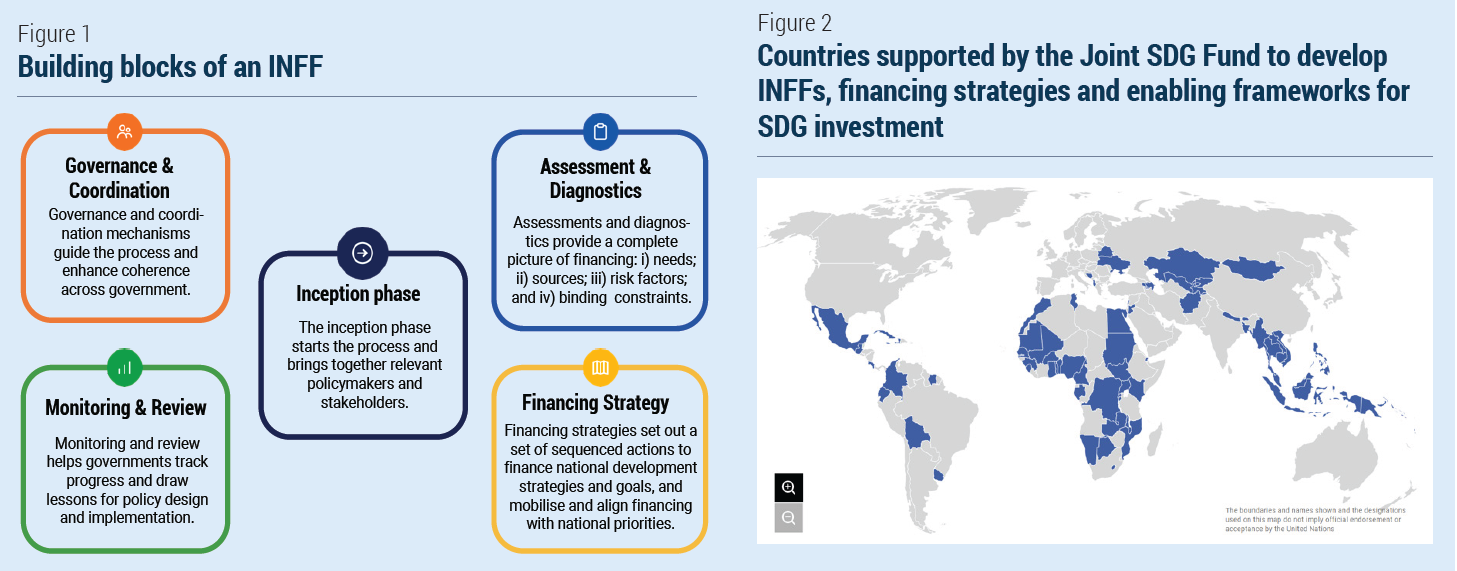

Such financing strategies are a key element of Integrated national financing frameworks (INFFs), a country owned planning tool that provide a framework for incorporating financing into national planning processes. Introduced in an earlier UNDESA policy brief, INFFs can be particularly useful in the current context to help shape the response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In this second policy brief, we unpack the importance of integrated financing strategies that can mobilize and align financing with recovery plans, while helping policymakers avoid unintended trade-offs and identify synergies and win-wins when financing sustainable development.

How can countries implement integrated financing strategies?

An integrated financing strategy identifies policy actions to mobilize funding for key priorities, and to align the broader financial system with those priorities. It thus typically includes measures across: ◆ Public finance, with a focus on integrating planning and public budgeting; ◆ Private finance and investment, including aligning policy and regulatory frameworks for private finance with sustainable development; ◆ Macro- and systemic issues, including debt sustainability, macro-economic and macro-prudential policies, and other issues related to financial market stability; ◆ Cross-cutting issues, such as the public-private partnerships or sector-specific policy issues. In formulating financing strategies, countries do not need to start from scratch—almost all countries have financing policies and institutional arrangements in place in these areas. The integrated financing strategy builds on these existing arrangements, and seeks to identify and close gaps, overcome incoherencies, and exploit opportunities.Step 1: Establish scope and financing policy objectives

The scope and form of the financing strategy will depend on country circumstances and needs. It may address broad financing needs associated with the entire national development plan or focus on a specific sector. Bosnia and Herzegovina, for example, is using the INFF process to explore private finance modalities that can unlock new sources of private capital over a 2 to 5 year horizon. In Bangladesh, the financing strategy will focus on three thematic priorities: climate finance, renewable energy and water and sanitation. In all cases it is imperative to bring in different stakeholders from beginning, including Ministries of Labour, Environment, Women and Children, as well as Social Services (to ensure all dimensions of sustainability are considered in the design of financing policies).Step 2: Identify policy options

National authorities can identify policy options by first mapping existing relevant policies and initiatives. Starting with current practices introduces policy-realism from the outset, as it reflects existing capacity and political economy constraints. It also helps ensure national ownership of the process and can serve to create consensus among key stakeholders of existing gaps that need to be addressed as apriority. To identify new policy and reform ideas, policymakers can consider local good practices, low hanging fruit, external good practices, and hybrid solutions. Local good practices are a first area of opportunity and refer to ideas that are already being acted upon but are not fully implemented. In some cases, these solutions can be scaled up or replicated in different sectors or areas. For instance, policymakers may replicate a successful project risk sharing facility in the renewable energy sector in other sectors, such as agribusiness. Low hanging fruit refer to ideas not yet acted upon, but which would require relatively little effort to implement. This could include updating tax laws to overcome inefficiencies in tax collection. Finally, external good practices refer to ideas that have proven themselves in other country contexts. For example, this could include reorganising the debt management office into a front, middle, and back office with a view to streamlining processes.

Step 3: Policy prioritization

All policy solutions will have associated costs and benefits, including trade-offs. For instance, environmental or labor market regulations can sometimes constrain investment. Eliminating them, while potentially attracting investment, will undermine other SDG priorities. Such trade-offs have to be made explicit in a policy prioritization process. Financing policies should also be risk-informed – they should contribute to reducing risks to sustainable development prospects, and not create new risk. For example, the economic and social costs of the pandemic could have been reduced with earlier investments in risk prevention and preparedness. Investments in social protection systems, which can be ramped up in time of need, can help vulnerable groups, households and societies manage risk and volatility, and protect them from poverty in the event of a crisis. In short, three overarching questions should be applied to all policy options identified in Step 2: ◆ Macro checks -- are policies consistent with macro-objectives, i.e., growth targets, debt sustainability targets, etc.? ◆ Coherence checks -- are policies aligned with all dimensions of sustainable development, or do they jeopardise any dimension of sustainability; what trade-offs/externalities need to be considered, do they have strong linkages across sectors and enable win-wins? ◆ Risk checks -- are policies sufficiently risk informed, or do they create new risk? Mainstreaming the coherence checks into policymaking process will help articulate trade-offs and make externalities explicit (see Chile example below). Ultimately trade-offs can then either be accepted, or remedies considered. In some cases, potential trade-offs or externalities can be reduced or avoided altogether by discrete policy interventions (e.g., with the help of corrective taxes, regulatory reforms, blended finance instruments, etc).

In addition to such ‘coherence and risk checks’, policy makers must also be mindful of preconditions and resource-requirements. Many technically sound proposals, e.g. emanating from international good practice, may not be administratively or politically feasible in the local context. Successful policy prioritization often implies a careful sequencing of interventions, and commitment to address ‘basics first’.

To check resource constraints and preconditions, the following questions should be asked:

◆ Have preconditions been considered (i.e., are the institutional preconditions in place, does it enjoy the required political backing, are there available instruments that could support its implementation)?

◆ Have resource requirements been considered (i.e., can it rely on existing capacity for effective implementation/ are financial resources available for its implementation)?

If policy options align with preconditions and resource checks, they present opportunities for ‘quick wins’ and immediate action. In other cases, longer-term solutions can be designed to alleviate constraints in the medium and long-term.

Step 4: Operationalization

To operationalize the strategy, the full list of actions to be undertaken, ranging from short term operational actions to long term strategic ones, should be brought together, along with modalities for monitoring and review (building block 3). The actions should align with the objectives outlined in Step 1. It is in within this context that the INFF methodology provides a foundation for action, not as a blueprint for reform, but as a starting point for locally driven reform processes.

Mainstreaming the coherence checks into policymaking process will help articulate trade-offs and make externalities explicit (see Chile example below). Ultimately trade-offs can then either be accepted, or remedies considered. In some cases, potential trade-offs or externalities can be reduced or avoided altogether by discrete policy interventions (e.g., with the help of corrective taxes, regulatory reforms, blended finance instruments, etc).

In addition to such ‘coherence and risk checks’, policy makers must also be mindful of preconditions and resource-requirements. Many technically sound proposals, e.g. emanating from international good practice, may not be administratively or politically feasible in the local context. Successful policy prioritization often implies a careful sequencing of interventions, and commitment to address ‘basics first’.

To check resource constraints and preconditions, the following questions should be asked:

◆ Have preconditions been considered (i.e., are the institutional preconditions in place, does it enjoy the required political backing, are there available instruments that could support its implementation)?

◆ Have resource requirements been considered (i.e., can it rely on existing capacity for effective implementation/ are financial resources available for its implementation)?

If policy options align with preconditions and resource checks, they present opportunities for ‘quick wins’ and immediate action. In other cases, longer-term solutions can be designed to alleviate constraints in the medium and long-term.

Step 4: Operationalization

To operationalize the strategy, the full list of actions to be undertaken, ranging from short term operational actions to long term strategic ones, should be brought together, along with modalities for monitoring and review (building block 3). The actions should align with the objectives outlined in Step 1. It is in within this context that the INFF methodology provides a foundation for action, not as a blueprint for reform, but as a starting point for locally driven reform processes.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations