Two “population billionaires”, China and India, face divergent demographic futures

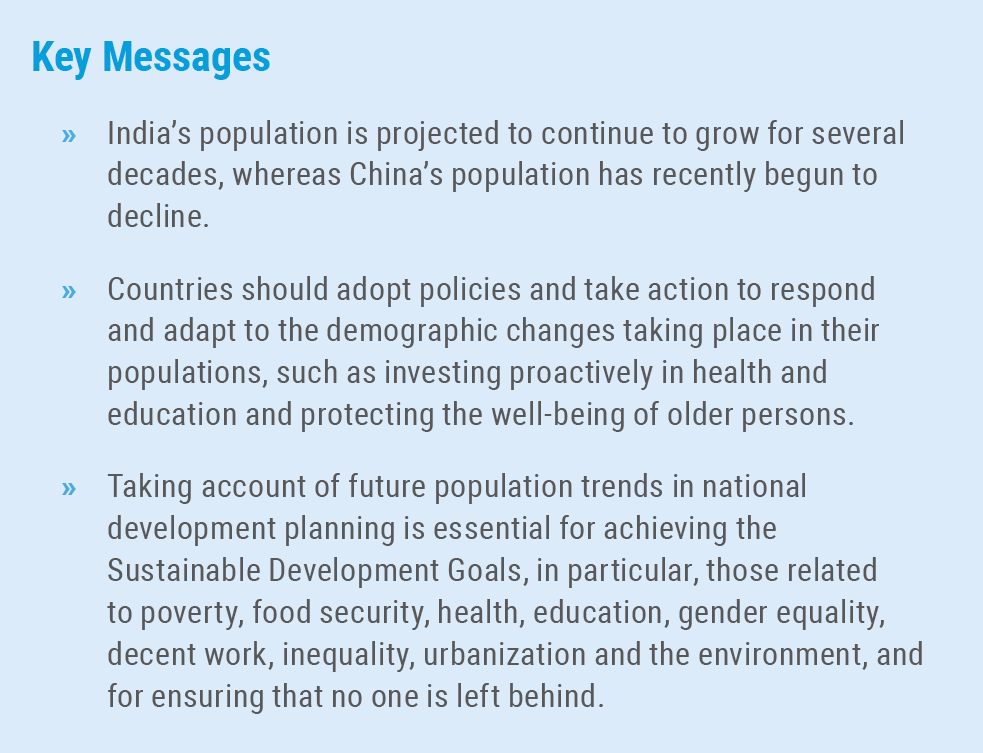

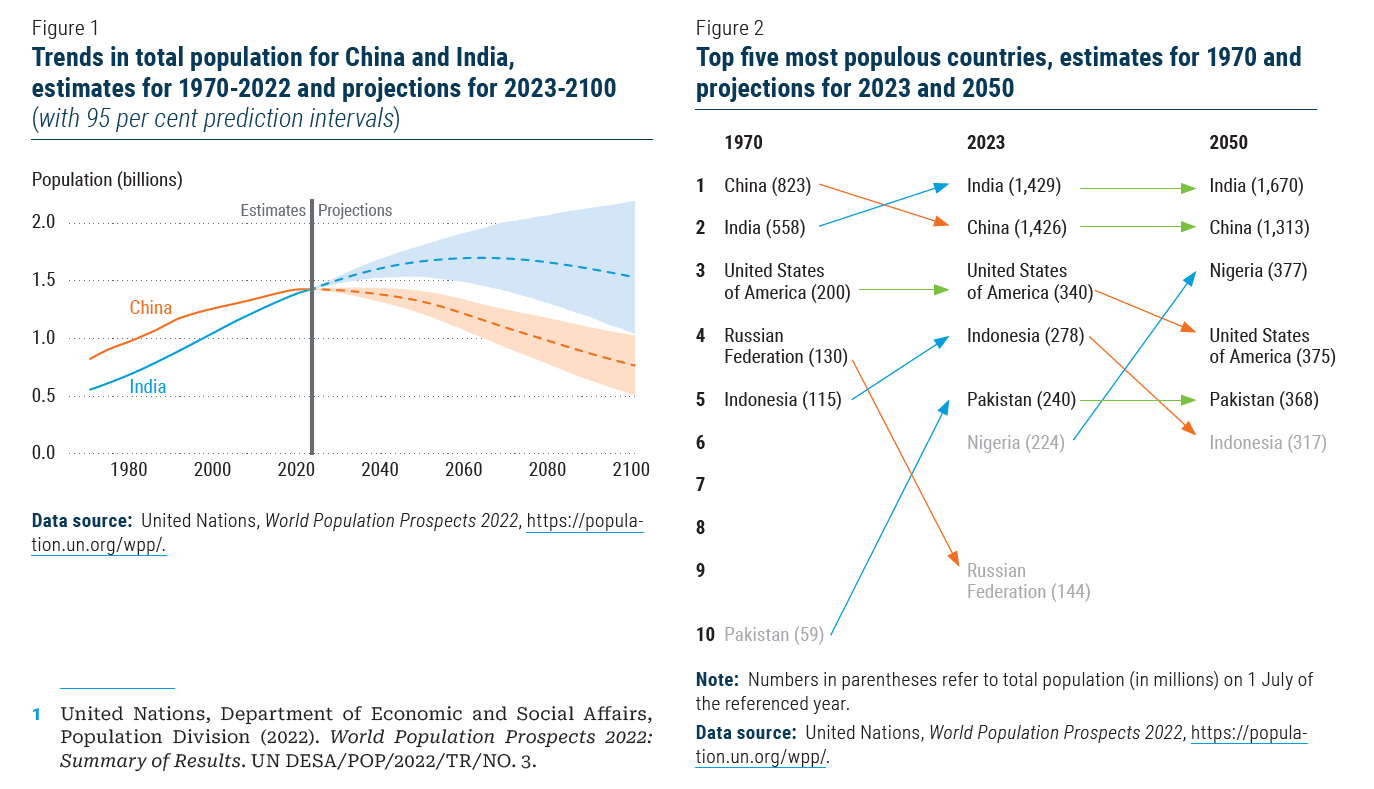

The latest estimates and projections of global population from the United Nations, indicate that China will soon cede its long-held status as the world’s most populous country. In April 2023, India’s population is expected to reach 1,425,775,850 people, matching and then surpassing the population of mainland China (figure 1). India’s population is virtually certain to continue to grow for several decades. By contrast, China’s population reached its peak size recently and experienced a decline during 2022. Projections indicate that the size of the Chinese population will continue to fall and could drop below 1 billion before the end of the century.

Censuses are key sources of information about population size and characteristics

Both China and India conduct regular population and housing censuses to enumerate and document their national populations, and both countries use the information obtained to inform their development planning. In China, the most recent census was taken in November 2020. More than a decade has passed since India’s most recent census in 2011. India’s planned 2021 census was delayed due to challenges associated with the COVID-19 pandemic and is now scheduled for 2024. To estimate and project the size of the Indian and Chinese populations for subsequent years after their last censuses, the United Nations relies on information about levels and trends in fertility, mortality and international migration obtained from vital records, surveys and administrative data (United Nations, 2022b). Uncertainty associated with the resulting estimates and projections implies that the date on which India is expected to surpass China in population size is approximate and subject to revision as more data become available.Current population trends in China and India are determined largely by fertility levels since the 1970s

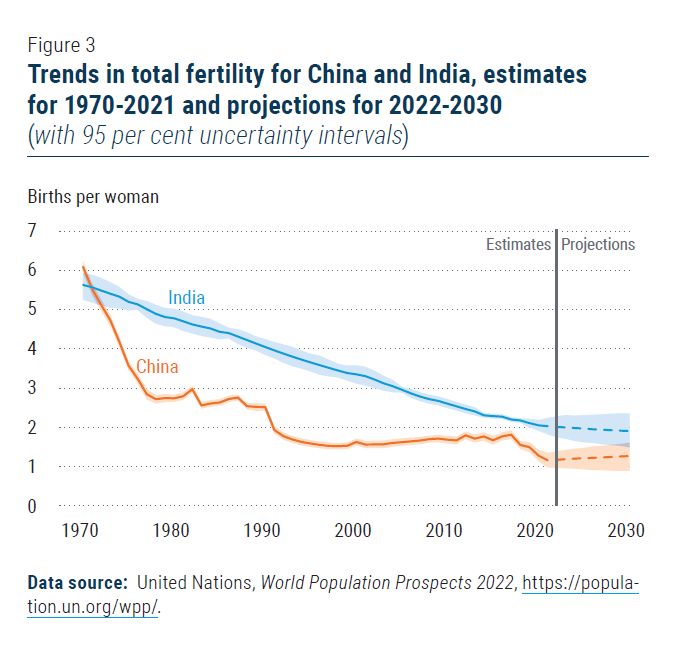

In 1971, China and India had nearly identical levels of total fertility, with just under 6 births per woman over a lifetime. Fertility in China fell sharply to fewer than 3 births per woman by the end of the 1970s (figure 3). By contrast, the fertility decline in India has been more gradual: it took three and a half decades for India to experience the same fertility reduction that occurred in China over just seven years in the 1970s.

In 2022, at 1.2 births per woman, China had one of the world’s lowest fertility rates; India’s fertility rate, at 2.0 births per woman, was just below the “replacement” threshold of 2.1, the level required for population stabilization in the long run. According to the United Nations’ latest projections, India’s population is expected to reach its peak size around 2064 and then to decline gradually.

China and India offer contrasting examples of national trajectories through the demographic transition towards longer lives and smaller families. The timing, speed and intensity of the demographic transition have differed markedly across countries and regions, depending on multiple factors of human development. Key determinants include improvements in nutrition and public health, which reduce mortality especially among children; increased levels of education, particularly for girls and women, often associated with declining levels of mortality and fertility; urbanization; expanded access to reproductive health-care services, including for family planning; and women’s empowerment and labour force participation.

In 1971, China and India had nearly identical levels of total fertility, with just under 6 births per woman over a lifetime. Fertility in China fell sharply to fewer than 3 births per woman by the end of the 1970s (figure 3). By contrast, the fertility decline in India has been more gradual: it took three and a half decades for India to experience the same fertility reduction that occurred in China over just seven years in the 1970s.

In 2022, at 1.2 births per woman, China had one of the world’s lowest fertility rates; India’s fertility rate, at 2.0 births per woman, was just below the “replacement” threshold of 2.1, the level required for population stabilization in the long run. According to the United Nations’ latest projections, India’s population is expected to reach its peak size around 2064 and then to decline gradually.

China and India offer contrasting examples of national trajectories through the demographic transition towards longer lives and smaller families. The timing, speed and intensity of the demographic transition have differed markedly across countries and regions, depending on multiple factors of human development. Key determinants include improvements in nutrition and public health, which reduce mortality especially among children; increased levels of education, particularly for girls and women, often associated with declining levels of mortality and fertility; urbanization; expanded access to reproductive health-care services, including for family planning; and women’s empowerment and labour force participation.

Population policies in China and India had different impacts

Many factors contributed to falling birth rates in China and India, but the relative contributions of each remain a matter of debate (Bongaarts and Hodgson, 2022). During the second half of the twentieth century, both countries made concerted efforts to curb rapid population growth through policies that targeted fertility levels. In China, the most notable policies were the “later, longer, fewer” campaign of the 1970s, which promoted later marriage, longer intervals between births and fewer children overall, as well as the stricter “one-child” policy, in effect from 1980 until 2015, which limited couples to one or two children with some exceptions (Wang and others, 2016). These policies, together with investments in human capital, changing roles for women and other factors, contributed to China’s plummeting fertility rate in the 1970s and to the more gradual declines that followed in the 1980s and 1990s. India also enacted policies to discourage the formation of large families and to slow population growth, including through its national family welfare programme beginning in the 1950s. However, under India’s federal structure, state governments were able to set their own policy priorities, resulting in varied impacts across different parts of the country. In Kerala and Tamil Nadu, where state governments emphasized socio-economic development and women’s empowerment, fertility declined earlier and at a more rapid pace, falling below the replacement level two decades before the country as a whole. Those states that invested less in human capital, especially for girls and women, experienced slower reductions in fertility, despite controversial mass sterilization campaigns and other coercive measures in some locations (Gupte, 2017; May 2012). India’s lower human capital investment and slower economic growth during the 1970s and 1980s, contributed to a more gradual fertility decline compared to China and, consequently, to more rapid and persistent population growth.Population ageing echoes historical declines in fertility

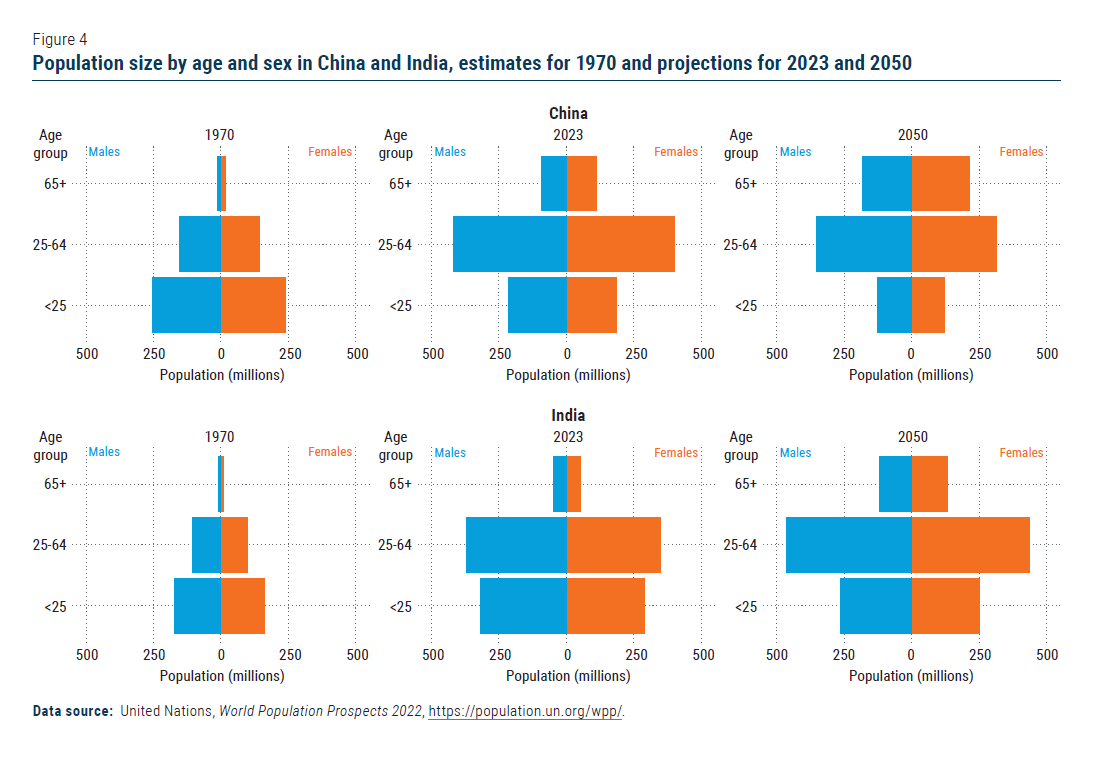

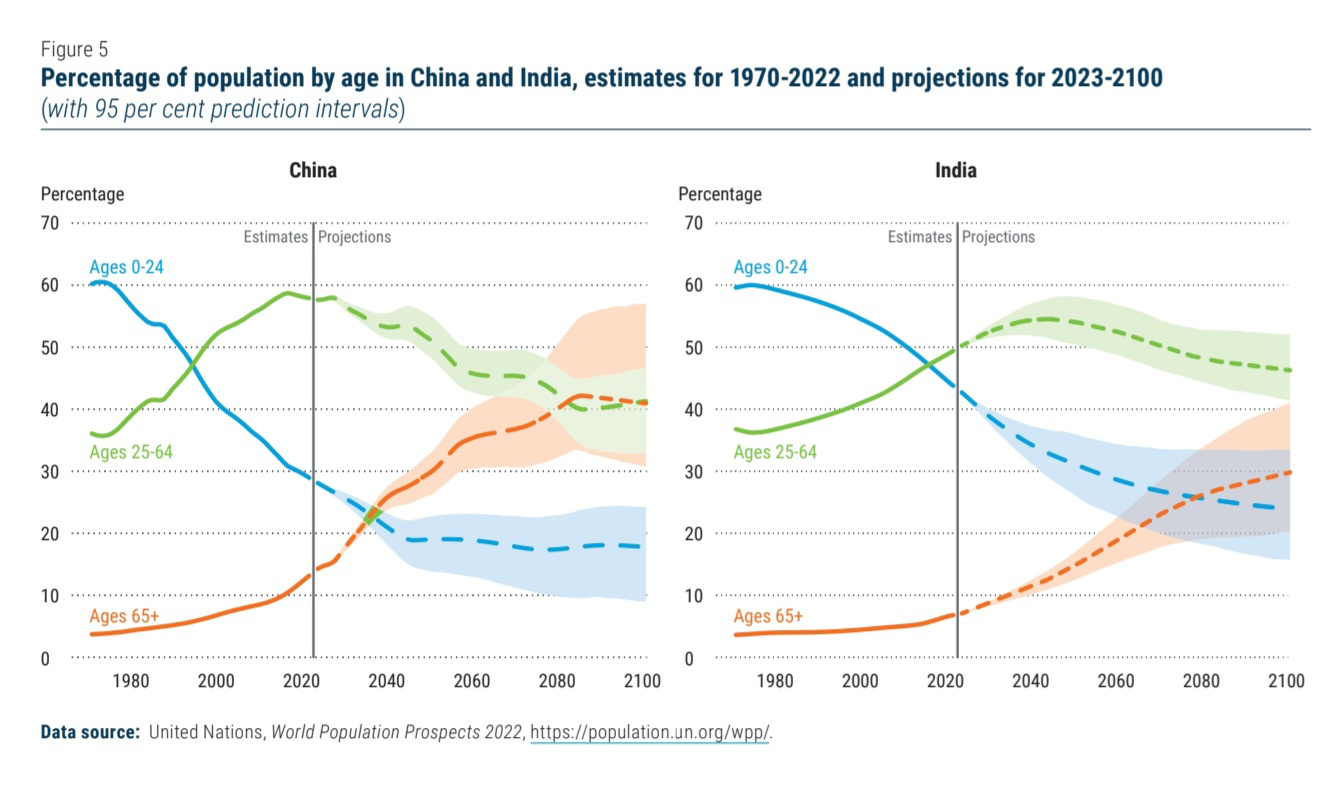

The ageing of human populations is an inevitable consequence of the demographic transition. Both China and India are experiencing a shift in their populations towards older ages. In fact, most countries are experiencing some degree of population ageing, though with important differences that stem from the varied pace and timing of the demographic transition (United Nations, 2017b, 2023). The divergent demographic paths taken by China and India since the 1970s are visible in the current age profiles of the two countries. In 1970, both countries had youthful populations, as illustrated by the pyramidal shape of their age and sex structures (figure 4). At that time, children and youth under age 25 comprised the largest age group, accounting for 60 per cent of the total population of both countries, whereas older persons aged 65 years or over made up less than 4 per cent.

China’s rapid fertility decline in the 1970s is echoed in its age distribution for 2023, wherein there are twice as many adults aged 25-64 years compared to children and youth below age 25. This surge in the proportion of population in the working age range facilitated an acceleration of economic growth on a per capita basis over this period (Yuan and Gao, 2020). Projections indicate that the percentage of China’s population aged 25-64 will peak in the coming years, closing the window of opportunity created by the changing age distribution.

Population ageing is unfolding more gradually in India than in China, and at a varied pace across states. Overall, the number of adults aged 25-64 in India exceeds the number of children and youth under age 25 by around 20 per cent. The number of adults of working age is projected to continue increasing both in number and as a proportion of the total population through mid-century, ensuring a continuing positive contribution of demographic change to per capita economic growth. Moreover, labour migration from the youthful northern and eastern states could bolster the size of the workforce in the relatively older southern states, prolonging the demographic dividend in those regions. Maximizing the potential benefits of the favourable demographic situation will depend critically on investments in the education and health of adolescents and youth and on policies to facilitate their productive employment and to ensure equal opportunities for women and girls (UNFPA India, 2018).

Both China and India are experiencing imbalances in the sex ratio at birth, with millions more boys than girls born since the 1980s. These skewed ratios are motivated by a strong preference for sons, which is achieved primarily through sex-selective abortion, a practice that has been outlawed in both countries. In some regions of India, post-natal discrimination continues to result in higher mortality rates for girls than for boys (Alderman and others, 2021), further exacerbating the imbalanced sex ratio. Among persons younger than 25 years in 2023, there are 116 males for every 100 females in China and 110 males per 100 females in India. Such imbalances may portend challenges for adult partnerships and family formation, with potential adverse consequences for social cohesion and intergenerational support, especially in communities where the patrilineal family-household is the traditional source of care and support for older persons (Srinivasan and Li, 2018).

The divergent demographic paths taken by China and India since the 1970s are visible in the current age profiles of the two countries. In 1970, both countries had youthful populations, as illustrated by the pyramidal shape of their age and sex structures (figure 4). At that time, children and youth under age 25 comprised the largest age group, accounting for 60 per cent of the total population of both countries, whereas older persons aged 65 years or over made up less than 4 per cent.

China’s rapid fertility decline in the 1970s is echoed in its age distribution for 2023, wherein there are twice as many adults aged 25-64 years compared to children and youth below age 25. This surge in the proportion of population in the working age range facilitated an acceleration of economic growth on a per capita basis over this period (Yuan and Gao, 2020). Projections indicate that the percentage of China’s population aged 25-64 will peak in the coming years, closing the window of opportunity created by the changing age distribution.

Population ageing is unfolding more gradually in India than in China, and at a varied pace across states. Overall, the number of adults aged 25-64 in India exceeds the number of children and youth under age 25 by around 20 per cent. The number of adults of working age is projected to continue increasing both in number and as a proportion of the total population through mid-century, ensuring a continuing positive contribution of demographic change to per capita economic growth. Moreover, labour migration from the youthful northern and eastern states could bolster the size of the workforce in the relatively older southern states, prolonging the demographic dividend in those regions. Maximizing the potential benefits of the favourable demographic situation will depend critically on investments in the education and health of adolescents and youth and on policies to facilitate their productive employment and to ensure equal opportunities for women and girls (UNFPA India, 2018).

Both China and India are experiencing imbalances in the sex ratio at birth, with millions more boys than girls born since the 1980s. These skewed ratios are motivated by a strong preference for sons, which is achieved primarily through sex-selective abortion, a practice that has been outlawed in both countries. In some regions of India, post-natal discrimination continues to result in higher mortality rates for girls than for boys (Alderman and others, 2021), further exacerbating the imbalanced sex ratio. Among persons younger than 25 years in 2023, there are 116 males for every 100 females in China and 110 males per 100 females in India. Such imbalances may portend challenges for adult partnerships and family formation, with potential adverse consequences for social cohesion and intergenerational support, especially in communities where the patrilineal family-household is the traditional source of care and support for older persons (Srinivasan and Li, 2018).

Both China and India must prepare for growing numbers of older persons

The number of older persons is growing rapidly in both China and India. This growth is linked to increasing numbers of births around the middle of the last century, as those cohorts are now reaching older ages, and to falling mortality risks that allow more people to survive to advanced ages. Between 2023 and 2050, the number of persons aged 65 or over is expected to nearly double in China and to more than double in India, posing significant challenges to the capacity of healthcare and social insurance systems. By 2040, persons aged 65 or over in China will outnumber those under age 25; and by 2050 they could comprise 30 per cent of the total population (figure 5). Countries like Japan and the Republic of Korea have experienced similar rapid population ageing, but at higher levels of economic development than has been achieved in China. In India, the ratio of older persons to those of working age is expected to remain lower than in China, reflecting the slower pace of population ageing in India.

By 2040, persons aged 65 or over in China will outnumber those under age 25; and by 2050 they could comprise 30 per cent of the total population (figure 5). Countries like Japan and the Republic of Korea have experienced similar rapid population ageing, but at higher levels of economic development than has been achieved in China. In India, the ratio of older persons to those of working age is expected to remain lower than in China, reflecting the slower pace of population ageing in India.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations