- Declining headline unemployment rates mask deeper labour market challenges in both developed and developing regions

- High youth unemployment not only bears significant costs for the individual but also damages the social fabric

- Long term investments in education, fostering entrepreneurship and enhancing social safety nets promote more inclusive labour markets

English: PDF (172 kb), EPUB (287kb)

Global issues

High youth unemployment presents a daunting challenge for policymakers around the world

The promotion of full and productive employment and decent work for all is a cornerstone of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In tandem with the acceleration in global economic activity, recent headline labour market indicators reflect gradual progress towards this challenging goal in the majority of developed economies, economies in transition and developing economies. In countries such as Germany, Japan, Mexico and the United States, unemployment rates have dropped to exceptionally low levels.

Headline unemployment rates, however, do not give a complete picture of the scale of labour market challenges that remain. Close to 200 million people are unemployed globally. Moreover, more than 40 per cent of the working population in low income countries live in extreme poverty. At the same time, more than 40 per cent of the world?s workers are in vulnerable forms of employment, with little or no access to social protection, low and volatile income, and high levels of job insecurity.[1] Job security has worsened in many economies over the last decade, alongside a rise in the share of involuntary part-time employment, a decline in coverage of collective bargaining and rising inequality.[2]

Women and youth face specific challenges in their job prospects. Both groups suffer relatively higher rates of unemployment, and youth are around three times as likely as adults to be unemployed. These challenges are well recognized in the 2030 Agenda, with several of the SDG targets specifically aimed at broadening the employment opportunities and quality of jobs for both groups.

Global concerns regarding the high levels of youth unemployment are longstanding. High youth unemployment is not just a loss to the individuals involved, but also bears a broader social cost. Studies show that an episode of unemployment when young, or transitioning to work during a recession, has large and persistent effects on lifetime potential wages, raises the probability of being unemployed in later years, and puts youth at risk of long-term social exclusion.[3] High levels of youth unemployment are also associated with slower development progress, a lack of social trust and a higher risk of social unrest. Given these costs, engaging with youth, smoothing the transition to work, and improving the quality of available jobs is a crucial policy priority.

A specific target set out in the SDGs is to ?By 2020, substantially reduce the proportion of youth not in employment, education or training? (NEET) (SDG target 8.6). The NEET measure of inactivity is preferred to the headline youth unemployment rate, as it is not distorted by the rising share of youth that remain in education beyond age 15 or cyclical impacts on participation rates. The global NEET rate stands at 21.8 per cent, compared to an unemployment rate of 13 per cent for 15?24 year olds. Rates are particularly high in Northern Africa, Southern Asia and Central and Western Asia, and more than three-quarters of those classified as NEET are young women.

Across the world, young people are faced with specific challenges when transitioning to work. Young people are much more likely to be in insecure, short-term or informal employment, with more than three-quarters of working youth in informal jobs that lack social protection and entail a substantial wage penalty. As a result, 160 million working youth worldwide live in poverty.[4] Structural transition in many countries, notably in North Africa and the Middle East, has decreased employment opportunities in the public sector, while job creation in the formal private sector remains slow, partly due to regulatory barriers to firm entry and limited credit availability. Social barriers also limit demand for private sector jobs, especially among women. Skills mismatch between formal education and labour market opportunities are pervasive. On the upside, young people are generally better prepared for the digital working environment, which has acted as a barrier for many older workers to access new types of jobs.

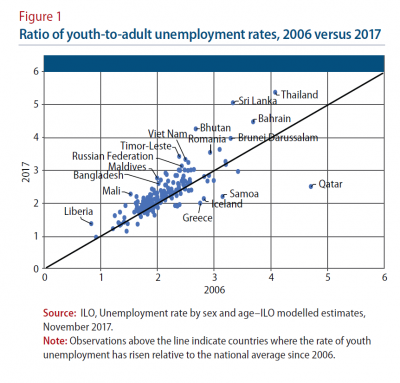

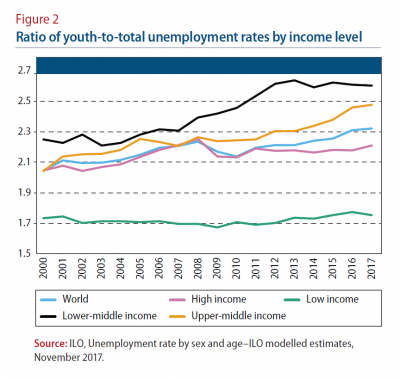

The global youth unemployment rate increased from 12.3 per cent in 2006 to reach 13 per cent in 2017. Over the same period, the rate of global adult unemployment has seen less variation, averaging 4?4.4 per cent. As a result, the relative incidence of youth unemployment?measured as the ratio of the youth unemployment rate to the total unemployment rate?has risen, reflecting a broad-based deterioration in relative prospects for youth in 75 per cent of countries worldwide since 2006 (figure 1). The deterioration has been most acute in upper-middle and lower-middle income countries (figure 2).

The global youth unemployment rate increased from 12.3 per cent in 2006 to reach 13 per cent in 2017. Over the same period, the rate of global adult unemployment has seen less variation, averaging 4?4.4 per cent. As a result, the relative incidence of youth unemployment?measured as the ratio of the youth unemployment rate to the total unemployment rate?has risen, reflecting a broad-based deterioration in relative prospects for youth in 75 per cent of countries worldwide since 2006 (figure 1). The deterioration has been most acute in upper-middle and lower-middle income countries (figure 2).

The Global Initiative on Decent Jobs for Youth[5] actively assesses policy initiatives to evaluate their impact on youth unemployment trends. Broadening access to early education has been shown to significantly improve youth employment opportunities. Supporting entrepreneurship, providing safety nets, employment services and quality apprenticeships, and upskilling rural job opportunities have also been shown to increase labour force participation and the probability of finding productive and decent employment.[6] However, the vast majority of countries that have seen significant declines in youth unemployment since 2000 have benefited from cyclical factors and job creation for all cohorts, while the incidence of youth unemployment relative to total unemployment has continued to rise. Some success, for example in Colombia, can be attributed to active youth entrepreneurship initiatives. However, not all active labour market policies are effective. Random control trials in Morocco, for example, found that training programmes only had a significant impact on those from more affluent backgrounds, who have greater access to finance.[7]

Demographic prospects will play a role in the prospects for youth employment going forward. Roughly 85 per cent of the world?s youth live in developing countries. The youth labour force is expected to expand rapidly across most of Africa and parts of South Asia over the next several years, but will decline in much of Europe and in Central and East Asia. In principle, a rapidly expanding youth cohort can deliver a ?demographic dividend?, as dependency ratios decline. However, absorbing new entrants into the labour market relies crucially on the ability to generate a sufficient number of high-quality jobs that are well-matched to available skills. In countries where the majority of youth are employed in the informal sector, prospects for meaningfully addressing the lack of quality jobs for young people remain daunting.

Developed economies

Japan: No change in restrictive immigration policy despite prevalent labour shortage

Japan?s labour market remains tight. The unemployment rate has declined to 2.7 per cent, the lowest since 1993. The ratio of job offers to applicants hit 1.56, the highest since 1974, while 86 per cent of university students due to graduate in March 2018 have already received job offers. Wage growth remains weak at 0.4 per cent in 2017, but the average hourly wage for part-time workers surged by 2.2 per cent, reflecting the depleting pool of part-time workers. The total labour force stood at 67 million in November 2017, which has barely changed over the last decade. However, the size of the traditional primary labour force?male, 15-64 years of age?has declined by 9 per cent over the decade. This has been offset by an increase in senior (over 65 years old) and female labour. While the government is relaxing immigration rules for skilled foreign labour, restrictive policies are expected to remain in place for low-skilled workers where the shortage is most acute.

Europe: Improving labour markets amid?continued challenges

Labour markets in Europe have continued to improve, albeit with significant variation between countries. Unemployment in the European Union (EU) decreased to 7.3 per cent in November compared to 8.3 per cent a year ago, marking the lowest level since October 2008. The lowest unemployment rates were registered in the Czech Republic at 2.5 per cent and in Germany and Malta at 3.6 per cent. In several countries, labour market conditions are equivalent to full employment, with companies facing a shortage of workers, posing a major obstacle to their operations. This has also filtered through to a further uptick in wages, underpinning the solid expansion of private consumption. Notwithstanding these improvements, unemployment rates remain elevated in Greece and Spain, at 20.5 per cent and 16.7 per cent, respectively. In addition, youth unemployment remains a serious problem across the region. In November, 16.2 per cent of youth were unemployed EU-wide, with the rate exceeding 30 per cent in Greece, Spain and Italy.

Meanwhile, steady economic growth in the EU members from Eastern Europe and the Baltics has supported a significant improvement in the region?s labour markets. In late 2017, the unemployment rate in most of these countries stood below the EU average. In Poland, the unemployment rate, at 6.5 per cent, is at its lowest since 1990. High youth unemployment, however, is a concern, with rates approaching 20 per cent in some countries. The consequent outflow of youth to more prosperous EU countries, while alleviating domestic labour market pressures to a certain extent, negatively impacts demographic dynamics and the sustainability of pension systems.

Economies in transition

Commonwealth of Independent States: Russian labour market relatively stable

Despite the recession in 2015?2016, the headline unemployment rate in the Russian Federation remained relatively stable, at 5.2?5.6 per cent. However, this masks numerous shifts to part-time work and massive wage arrears. For the smaller economies of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), assessments of labour markets are complicated by the large informal economy. Although in certain cases the rate of registered unemployment is less than 1 per cent (due to weak incentives to register), labour force surveys suggest double-digit figures. Meanwhile, the economic upturn in the Russian Federation has created more favourable conditions for seasonal migrants from the Central Asian countries, mostly in low-wage activities.

In South-Eastern Europe, unemployment remains staggeringly high in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. In the latter, the registered unemployment rate stood at around 22 per cent in 2017. Average youth unemployment for the region is estimated at 48 per cent. The labour force participation rate remains relatively low while certain social norms in the region create barriers for women to enter the workforce. The gradual shift to higher value-added activities exposes the mismatch between the education system and the new skills required by companies, generating outward migration pressures for discouraged youth.

Developing economies

Africa: Jobs and skills mismatch impact the labour market

In the face of stringent fiscal adjustment, Tunisia is facing social unrest. While GDP growth is forecast to reach 3.2 per cent in 2018, the current momentum has proved insufficient to improve the employment situation. In the third quarter of 2017, the unemployment rate stood at 15.3 per cent. While it has declined from a peak of 18.9 per cent in 2012, the rate remains well above the 12.5 per cent recorded in 2006. The composition of the unemployed has also changed over the last decade. In 2006, the unemployment rate among those with a university education stood at 17.0 percent. This segment of the population was the most affected during the period of social unrest in 2012, when the graduate unemployment rate surged to 34.2 per cent. Graduate unemployment rates remain above 30 per cent in Tunisia, and constitute a crucial socioeconomic destabilizing factor. Elevated graduate unemployment is also a challenge in Morocco. In the third quarter of 2017, the overall unemployment rate stood at 4.2 per cent, while that of graduates stood at 18.2 per cent.

Meanwhile, the unemployment rate in South Africa has gradually risen over the last decade, from 23.2 per cent in the first quarter of 2008 to 27.7 per cent in the third quarter of 2017. In contrast with Morocco and Tunisia, however, the graduate unemployment rate remains low in South Africa, at 5.4 per cent. Instead, unemployment is concentrated among those without a high school diploma, where the rate of joblessness stands at 32.7 per cent. In Nigeria, the unemployment rate stood at 8.9 per cent in the third quarter of 2017. Both the most and least educated struggle to find jobs, as 17.6 per cent of those with post-secondary degrees and 10.8 per cent of those with incomplete primary schooling are unable to find work.

East Asia: Policymakers to prioritize job creation and the expansion of social safety nets in 2018

Given the favourable short-term macroeconomic outlook, the East Asian economies have more policy space to accelerate structural reforms to strengthen economic resilience and improve the quality of growth. Notably, the region is enhancing efforts to address persistent structural issues in domestic labour markets. In 2017, vulnerable employment accounted for more than half of total employment in countries such as Indonesia, Myanmar, Thailand and Viet Nam. Amid insufficient job creation, high unemployment rates among the younger generation is also a growing concern for Indonesia, the Philippines and Taiwan Province of China, where youth unemployment rates range from around 8 ? 12 per cent. These challenges not only pose a constraint to productivity growth, but are also weighing on the region?s progress in tackling inequality and reducing poverty rates.

Against this backdrop, policymakers recently announced a range of measures to promote stronger employment growth and expand social protection. In 2018, the Republic of Korea and Myanmar will increase minimum wages by 16 per cent and 33 per cent respectively, while Thailand is raising its national minimum wage for the first time in five years. In the Republic of Korea, the authorities plan to increase welfare expenditure this year by 17 per cent to about 136 billion dollars (8 per cent of GDP), amid rising concerns over an ageing population. Planned measures include raising pensions, expanding jobs in social services and widening health insurance coverage. Pension reforms will also be a focus for Chinese policymakers, as the authorities continue to improve the coordination of pensions across provinces. Meanwhile, Indonesia has prioritised human capital development in 2018, with plans to expand vocational training and targeted apprenticeship programmes, amid efforts to upskill its labour force and reduce dependence on commodities.

South Asia: Improving job creation, especially for youth, remain as a key challenge for India

The Indian economy has become the fastest-growing emerging economy, driven by robust private consumption and sound macroeconomic policies. The medium-term outlook is also favourable, supported by the ongoing implementation of structural reforms. However, translating this into substantial labour market improvements is crucial in order to lift living standards, reduce poverty and forge a more inclusive development trajectory. In this context, a key challenge for the Indian economy is to improve job creation rates. There are rising concerns about the capacity to generate enough jobs to absorb the rapidly expanding labour force. Job creation in the formal sector has been anaemic, leaving many workers under-employed or with low-salary jobs. Sectors such as construction, manufacturing, and information technology and business process outsourcing have exhibited a weak performance. In addition, the situation for youth is particularly worrisome. Well-educated youth are struggling to find jobs in the formal sector, with most of them being absorbed in low-paying and vulnerable jobs in the informal sector. Some estimates also suggest that the NEET rate for youth is about 30 per cent. This issue is important given the vast potential benefits of India?s ?demographic dividend?. More than 60 per cent of the population is of working age and about 12 million people enter the labour force every year. The benefits, however, can only be realized if the country is able to generate sufficient productive and quality jobs. Several challenges lie ahead. Notably, productivity gains in the agricultural sector, as well as the more widespread use of automation technologies, can exert higher pressures on rural to urban migration.

Western Asia: Growing university-educated job seekers

The pattern of employment dynamics in Western Asia is less cyclical, largely reflecting structural changes in population and education. Some countries in Western Asia have registered a remarkable rise in tertiary education enrolment. The gross enrolment ratio for tertiary education rose from 29.7 per cent in Saudi Arabia in 2007 to reach 63.1 per cent by 2015. In Turkey, the ratio rose from 38.5 per cent to 94.7 per cent over the same period. However, the rapid increase in the university-educated population has yet to be effectively translated into economic benefits, as both countries have witnessed rising university-educated unemployment, particularly among female graduates. As of October 2017, the unemployment rate among those with a higher education diploma stood at 9.0 per cent for men and 18.1 per cent for women in Turkey. Unemployment rates for those with less than a high school education stood at 8.2 per cent for men and 10.9 per cent for women. The same trend can be seen in Saudi Arabia where the unemployment rate for university graduates stood at 7.3 per cent for men and 33.9 per cent for women in the third quarter of 2017. In the same period, 40 per cent of the unemployed were female graduates. While the growing tertiary education enrolment reflects the success of education policy in the region, the failure to provide decent employment opportunities for graduates presents an economic challenge and increases social tensions.

Latin America and the Caribbean: Regional labour market is showing signs of improvement

As the economic recovery strengthens, the region?s labour market is showing signs of improvement. Excluding Brazil, the average regional unemployment rate fell from 6.1 per cent in 2016 to 5.8 per cent in the third quarter of 2017,[8] marking the first decline in three years. In Brazil, the unemployment rate has also started to trend downwards after reaching an all-time high of 13.7 per cent in March 2017. Across the region, employment in manufacturing is recovering, following a sharp contraction in 2015?16. Youth unemployment, however, remains pervasive in most countries. About one in five people aged 15?24 failed to find a job ? three times the rate for those aged 25 and above. Even more worrisome is the fact that more than half of the jobs available to young people are in the informal economy, with no contract, benefits and social protection. This underscores the importance of boosting economic dynamism, while addressing structural barriers to formal employment, particularly for youth. Strong policy efforts are needed if the region wants to expand on the labour market gains made between 2000 and 2015. New evidence[9] indicates that active labour market policies (ALMPs), which include training programmes, employment subsidies, self-employment and micro-enterprise creation programmes, and labour market intermediation services, are particularly effective for young people and can foster formal employment. While ALMPs in the region often target men, they appear to be more effective

for women.

[1]???? International Labour Organization (2018), World Employment Social Outlook ?Trends 2018, available from http://www.ilo.org/global/research/global-reports/weso/2018/lang--en/in….

[2]???? Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2017), Employment Outlook 2017, available from http://www.oecd.org/els/oecd-employment-outlook-19991266.htm.

[3]???? Bell, David, and David G. Blanchflower (2011), Young people and the Great Recession, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, vol., Issue 2, pp. 241?267; and Kahn, Lisa (2010), The long-term labour market consequences of graduating from college in a bad economy, Labour Economics, vol. 17, Issue 2, pp. 303-316.

[4]???? International Labour Organization (2017), Global Employment Trends for Youth 2017, available from http://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/global-employment-trends/W….

[5]???? See http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/youth-employment/databases-platforms/g….

[6]???? International Labour Organization (2017), Promoting youth employment and empowerment of young women in Jordan, Impact Report Series, Issue 9.

[7]???? Bausch, J. and others (2017), The impact of skills training on the financial behaviour, employability and educational choices of rural young people, ILO Impact Report Series, Issue 6.

[8]???? International Labour Organization (2017), Labour Overview for Latin America and the Caribbean. Executive Summary, available from http://www.ilo.org/caribbean/information-resources/publications/WCMS_61….

[9]???? Escudero, Ver?nica, and others (2017), Active labour market programmes in Latin America and the Caribbean: Evidence from a meta analysis. IZA Institute of Labour Economics. Discussion Paper No. 11039.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations