Subdued global outlook amid persistent uncertainties

Subdued global outlook amid persistent uncertainties

Global economic growth stays below pre-pandemic trends

The world economy has shown remarkable resilience, with global growth projected at 2.8 per cent in 2025, the same as in 2024, and 2.9 per cent in 2026. This stability has been underpinned by continued disinflation, softening commodity prices, and monetary easing in many countries. However, ongoing conflicts, geopolitical tensions and potential trade restrictions, as well as climate risks pose significant challenges going forward (figure 1). The global economy is set to grow at a slower pace than the pre-pandemic average of 3.2 per cent recorded between 2010 and 2019, reflecting ongoing structural challenges such as weak investment, slow productivity growth, high levels of debt, and demographic pressures. Many developing countries are still experiencing scarring effects from the pandemic and other shocks of the past few years. The growth outlook for the least developed countries, landlocked developing countries, and small island developing States is challenging, with growth projected to remain below trend levels. While the green transition and technological advancement have the potential to boost growth, the benefits will not be evenly distributed across countries. Many developing countries continue to struggle with mobilizing financing for critical investments in infrastructure, technology, and human capital. Additionally, they face challenges in leveraging their abundant workforce to move up the manufacturing and services value chains.

Regional growth prospects are diverging

Economic growth in the United States is projected to moderate from a robust 2.8 per cent in 2024 to 1.9 per cent in 2025, amid weaker labour market performance and looming public spending cuts. Economic growth in China is expected to remain just below 5 per cent in the coming years, constrained by subdued consumption growth, ongoing weakness in the property sector, and the challenges posed by a shrinking population and rising trade tensions. Japan and Europe are forecast to experience modest economic recovery in 2025 and 2026, following weaker-than-expected growth in 2024.

Most developing regions are expected to see an uptick in economic growth in 2025 and 2026. Africa is projected to experience a slight growth acceleration, driven by recovery in the region’s largest economies—Egypt, Nigeria, and South Africa. Latin America and the Caribbean is also projected to see a mild growth recovery, supported by improvements in private consumption, easing monetary policies, and stronger export growth. Growth in Western Asia is expected to strengthen in 2025, driven by improved prospects in Saudi Arabia and Türkiye, the region’s largest economies. Economic performance in the region’s major oil-exporting countries is forecast to improve thanks to the gradual easing of oil production cuts. The near-term outlook for South Asia is expected to remain robust, driven by strong performance in India and economic recovery in other regional economies. East Asia is expected to experience a slight moderation of economic growth during the forecast period. While the region benefits from increasing global demand for products enhanced by artificial intelligence (AI), it faces intensifying geopolitical risks, rising trade tensions, and potentially weakening import demand from main trading partners. Similarly, in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), growth is expected to decline in 2025 due to an anticipated slowdown in the Russian Federation.

Vulnerable countries face a slower growth outlook post-pandemic

The economic outlook for vulnerable countries, such as the least developed countries (LDCs), landlocked developing countries (LLDCs), and small island developing States (SIDS), remains below pre-pandemic levels. Economic growth in LDCs is forecast at 4.6 per cent in 2025 and 5.1 per cent in 2026, falling short of the 5.4 per cent average growth recorded between 2010 and 2019. Additionally, most of these countries have experienced downward revisions to their 2025 growth forecasts.

Vulnerable countries face numerous challenges, including rising debt servicing burdens, limited fiscal space, and weak investments. Conflict, political instability, and rising trade tensions often exacerbate their economic difficulties. Many remain heavily dependent on commodity exports, leaving them particularly exposed to global market fluctuations. Climate change exacerbates their problems, as vulnerable countries are both more susceptible and less prepared for extreme weather events and natural disasters. The deteriorating growth outlook for vulnerable countries threatens their sustainable development prospects and risks entrenching or deepening extreme poverty.

Inflation and food security are improving, but threats remain

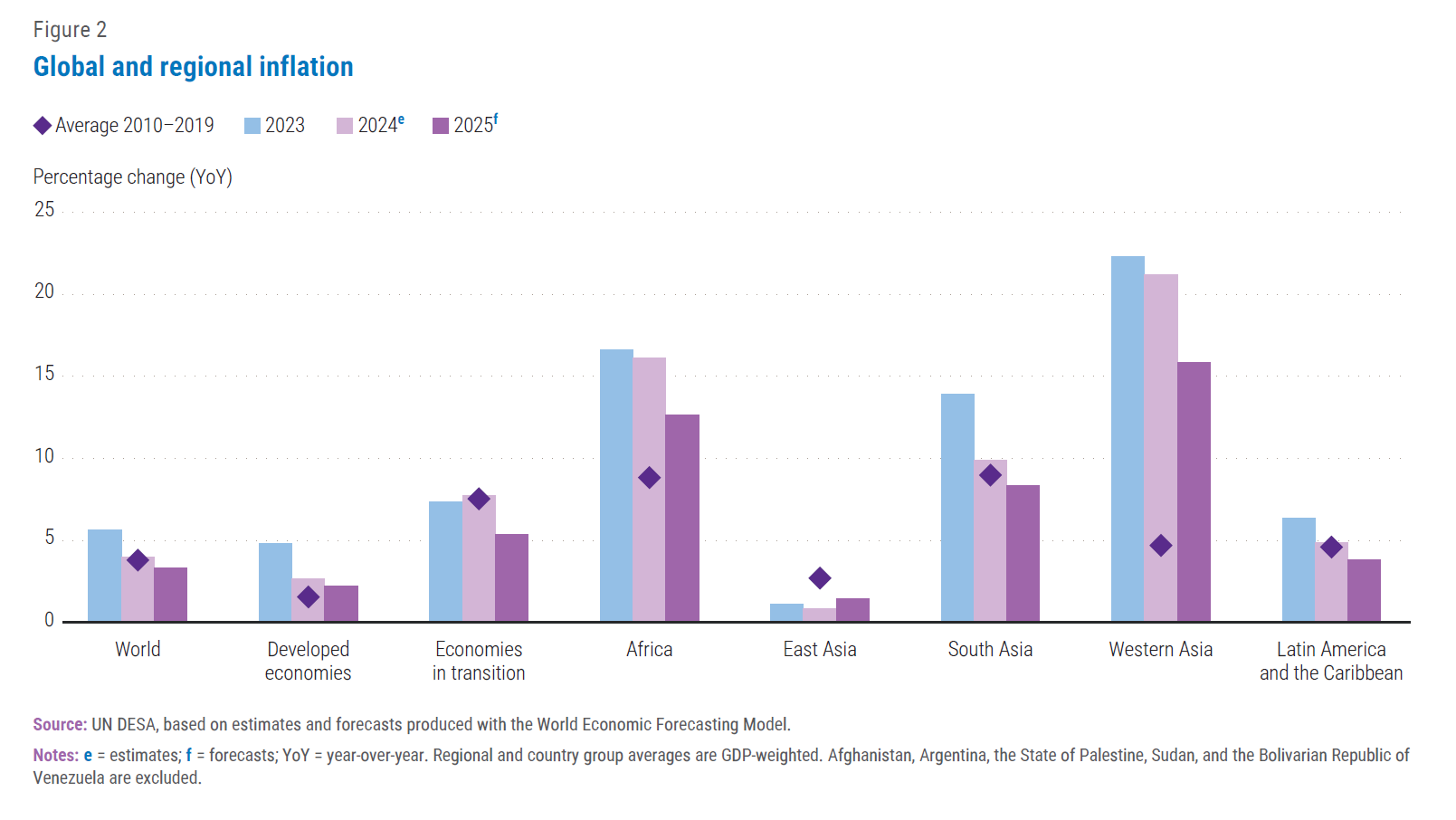

Global inflation has eased, with headline inflation falling from 5.6 per cent in 2023 to an estimated 4.0 per cent in 2024 (figure 2). However, the pace of disinflation has slowed due to sticky prices in housing and other services sectors as well as tight labour markets in developed economies. Inflation is projected to decline further to 3.4 per cent in 2025, although this outcome will depend on how trade restrictions evolve. In developed countries, inflation is expected to stabilize around central bank targets, creating room for a further gradual easing of monetary policy. In developing countries, inflation is forecast to continue declining but to remain above its long-term average in regions such as Africa and Western Asia, with some countries still experiencing double-digit inflation. Meanwhile, the prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity has decreased slightly but remains above pre-pandemic levels.

Upward risks to the inflation outlook remain significant. Renewed supply shocks in global commodity markets could drive up energy and food prices. Additionally, trade restrictions by major economies may push up prices in domestic markets, while disrupting supplies in global markets. Moreover, climate-related shocks, such as heatwaves, droughts, and floods threaten crop yields, intensifying pressures on food prices and endangering shipping channels and hydroelectric power generation.

Strong labour markets lead to higher wages in developed countries

In developed economies, labour market conditions remained broadly favourable in 2024, despite persistent sluggishness in some large European Union economies. By mid-2024, total employment in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries had surpassed the pre-pandemic level by almost 4 per cent (OECD, 2024). The labour force participation rate also exceeded pre-pandemic levels, reaching its highest value since 2008. Notably, the significant rise in female economic activity during the post-pandemic period has further narrowed gender gaps in employment. Tight labour markets and slowing inflation have contributed to higher real wages in most developed countries. In contrast, developing economies continue to grapple with high youth unemployment, skills mismatches, and elevated levels of informal and subsistence employment. Demographic pressures are expected to exacerbate these challenges, particularly in regions with rapidly growing youth populations.

International trade rebounds, but threats loom large

Global trade rebounded in 2024, growing at 3.4 per cent driven by improvements in merchandise trade and a robust expansion in services trade, particularly travel services. Part of this growth, however, reflects low base effects, as trade in 2023 was exceptionally weak due to inflationary pressures and the lingering impact of high energy prices. Moreover, some of the increased trade in 2024 may be due to the front-loading of orders from China in anticipation of potential trade restrictions in 2025.

The growth rate for world trade is projected to moderate to 3.2 per cent in 2025. However, the outlook remains uncertain, weighed down by geopolitical developments, uncertainties over the extent of tariffs and other trade restrictions, commodity price fluctuations, and potential softening of services trade. Trade tensions intensified in 2024, with the United States, Canada and the European Union imposing new tariffs on selected imports from China, including electric vehicles (Rokosz, 2024). The United States has recently announced its intention to expand tariffs on several key trading partners, but the timeline and scope of these restrictions remains uncertain. Equally uncertain are the ramifications of such tariffs, which could be determined by a range of factors including responses by consumers and businesses as well as possible retaliatory measures.

Investments improve amid challenges

Investments improve amid challenges

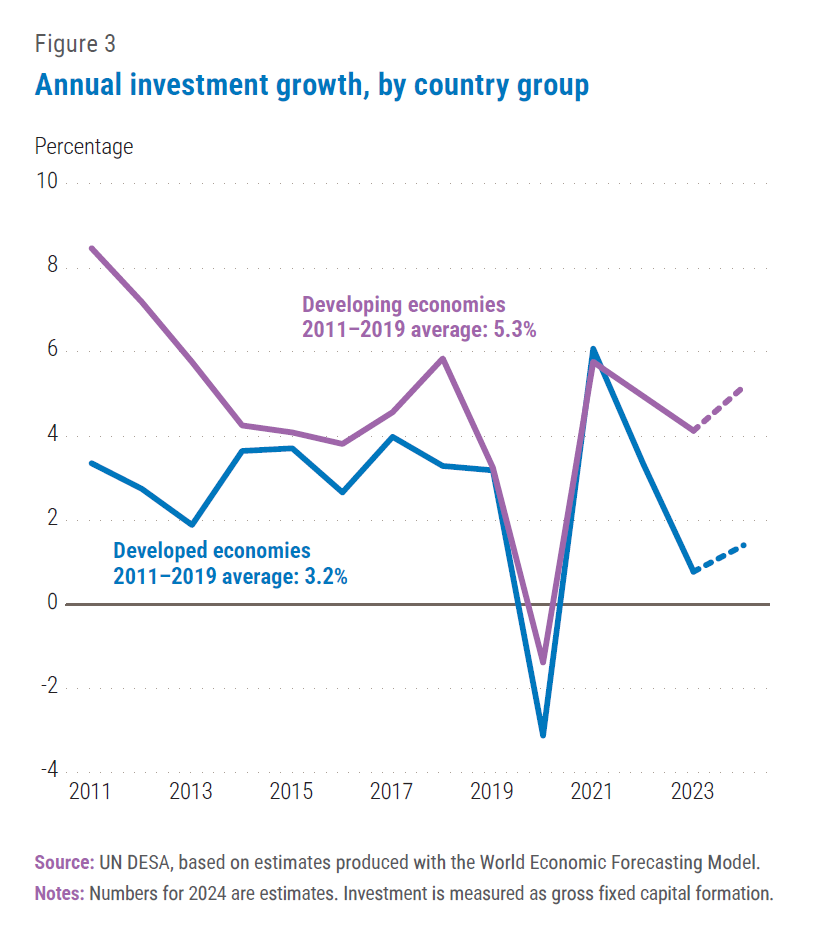

Global investment grew by 3.4 per cent in 2024 after a two-year slump (figure 3). Growth was particularly strong in East Asia and South Asia, driven by investments in new supply chains, especially in India, Indonesia, and Viet Nam. In China, robust growth in manufacturing investment (9.2 per cent) and high-tech industries (10.0 per cent) offset contractions in investment in property development and infrastructure (State Council Information Office, China, 2024). In Latin America and the Caribbean, investor confidence was dampened by increased commodity price volatility. Similarly, investment growth in Africa and Western Asia remained subdued, with high debt servicing burdens and political instability discouraging new investments.

Opportunities for global investment growth are present in sectors such as clean energy and technology, particularly AI and digitalization. However, challenges remain, including high borrowing costs, geopolitical uncertainties, and fiscal consolidation in many countries. As developed countries implement policies to promote domestic investment, developing economies will face new challenges in attracting foreign direct investment.

Central banks shift to easier monetary policy

Most central banks shifted to monetary easing in 2024 in response to moderating inflationary pressures and concerns over high financing costs. The European Central Bank initiated this policy shift in June, followed by the Bank of England in July and the Federal Reserve in September. The People’s Bank of China accelerated its easing measures, while the Bank of Japan diverged by adopting a tightening stance. By November 2024, 67 out of 108 central banks, mostly in developed and Asian economies, had eased their monetary policy stances.

The global trend of monetary easing is expected to gradually reduce financing costs in many economies. However, uncertainty regarding the duration and intensity of the Federal Reserve’s and European Central Bank’s easing cycles poses challenges. Moreover, the divergence between interest rate cuts and quantitative tightening (QT) introduces new complexities and risks. As liquidity is drained from the banking system, the projected increase in funding demand adds further pressure (IMF, 2024). The reliance on market-based funding, particularly repurchase agreements (repos), makes financial institutions more vulnerable to liquidity fluctuations, potentially undermining the effectiveness of monetary easing and creating risks for the broader financial system. The recent global sell-off of government bonds, which drove up bond yields across many countries, highlights shifting investor expectations around monetary easing, fiscal policy and broader economic uncertainties.

The Federal Reserve and European Central Bank are treading carefully to balance the policy trade-offs between price stability and growth in their respective economies, with current projections pointing at relatively shallow and gradual easing in 2025. The complex interplay between growth, inflation, interest rates, and liquidity necessitates the careful monitoring of both the economic and financial sectors to ensure effective policy implementation in support of growth and stability objectives.

International finance grows amid loosening monetary policy and strong investor demand

In 2024, cross-border financing resumed growth after stagnating since 2022, driven by loosening monetary policy and strong investor demand (figure 4). The net international investment position (NIIP) of the United States increased by 24 per cent year-on-year to -$22.5 trillion (77 per cent of GDP) in 2024. This reflects the growing appeal of financial assets in the United States due to stronger economic performance and higher expected returns compared to other countries. Indeed, the US dollar strengthened markedly in the second half of 2024 against major currencies.

Among other G20 economies, large net debtors included Brazil (36 per cent of GDP), Mexico (37 per cent), and Türkiye (33 per cent). Germany (74 per cent of GDP), Japan (83 per cent) and China (16 per cent) remained the largest creditors. Several least developed countries with a large negative NIIP, such as Mozambique (328 per cent), Bhutan (129 per cent) and Cambodia (117 per cent), face external financing constraints and a high risk of debt distress.

Looking ahead to 2025, the outlook for international finance will largely depend on the current monetary easing cycles by major developed country central banks which affect financing costs and broader economic conditions in many economies. However, uncertainties remain, such as investor concerns over the unwinding of the yen carry trade—a major source of market volatility in 2024—elevated long-term government bond yields, and the strength of the US dollar. These factors could further worsen the external financing constraints faced by many developing countries.

Fiscal policy faces challenges in the aftermath of shocks

In 2024 both developed and developing countries faced significant fiscal challenges as they grappled with the lingering effects of recent shocks and a challenging macroeconomic environment. Historically high levels of public debt, elevated interest rates, and weaker exchange rates against the US dollar have increased pressure to consolidate public finances to improve debt sustainability and rebuild fiscal buffers. At the same time, governments are contending with mounting public spending demands to address demographic shifts, economic and national security concerns, growing climate risks, and the need for investment in the energy transition and sustainable development.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis in many countries contributed to a longer-term trend of rising public debt as governments implemented expansionary fiscal measures to support households and businesses, while experiencing revenue shortfalls due to weaker economic activity. By the end of 2024, global public debt reached an estimated 95.1 per cent of global GDP. The general government gross-debt-to-GDP ratio exceeded 80 per cent in eight of the world’s ten largest economies, including China, Japan and the United States. In all developing regions except Western Asia, the average public-debt-to-GDP ratio stood above 65 per cent, with particularly strong increases in Africa and East Asia over the past two decades. Fiscal deficits also remained substantial in 2024. In the United States, the general government deficit widened to an estimated 7.6 per cent of GDP in 2024—one of the largest deficits outside of a war, recession, or emergency. Despite efforts of many European Union member countries to improve their fiscal balance, the average fiscal deficit was still about 3 per cent of GDP in 2024.

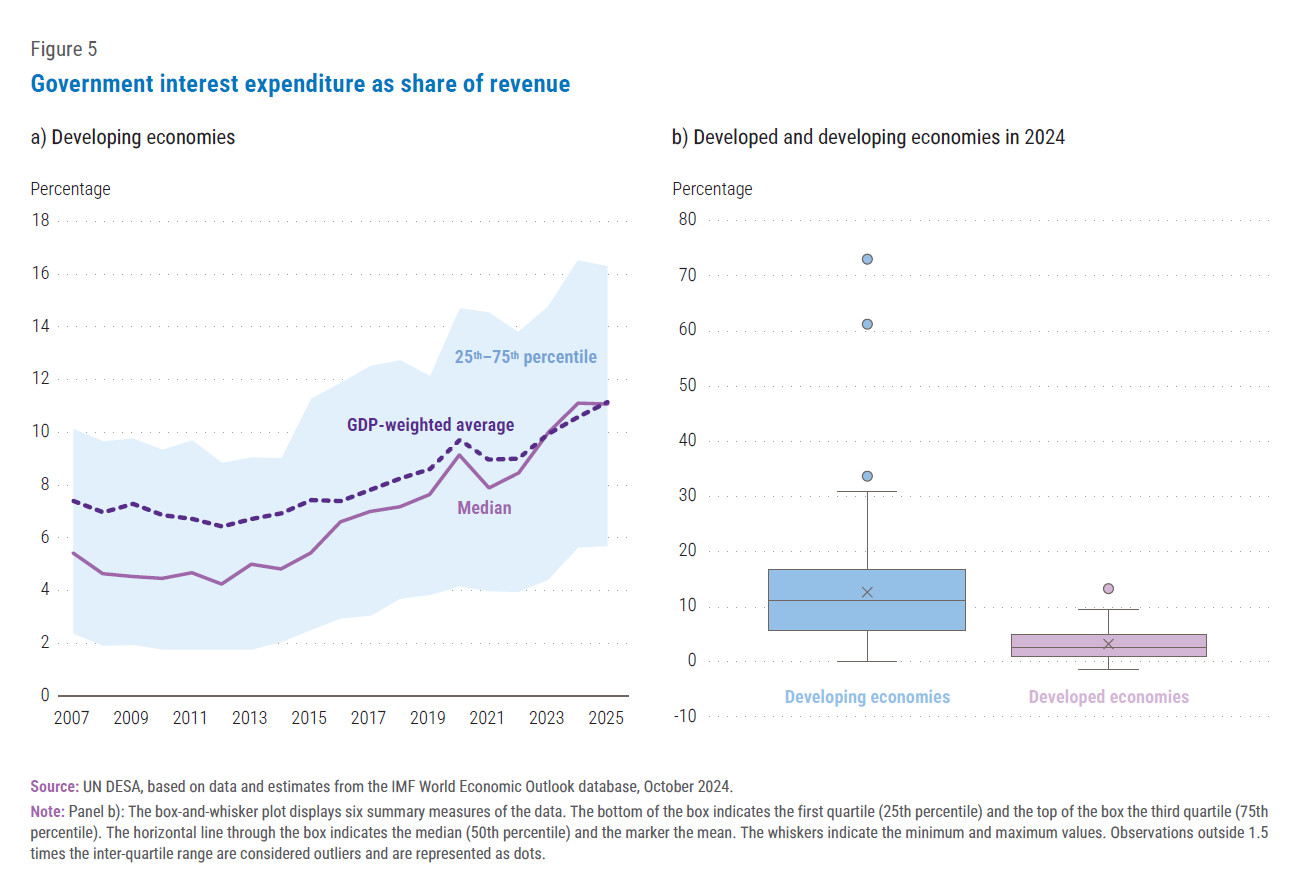

In most developing countries, fiscal space remains severely constrained by elevated debt levels, high interest rates, the strength of the US dollar, and subdued economic growth (figure 5). Fiscal challenges are most acute in Africa, where the rapidly growing debt-servicing burden is increasingly crowding out resources for essential public services and investment. Average interest payments as a percentage of government revenues in Africa (calculated on a GDP-weighted basis) reached an estimated 27 per cent in 2024, up from 19 per cent in 2019 and only 7 per cent in 2007. However, fiscal consolidation efforts are encountering significant pushback in some countries.

Many governments are expected to tighten fiscal policy in 2025, aiming to reduce public debt burdens. However, efforts to boost government revenues are often hindered by inadequate institutional capacities and public resistance to higher taxes. Policymakers must strike a delicate balance between strengthening fiscal sustainability and avoiding measures that would further strain household finances and social stability. Preserving critical public investment in areas such as infrastructure, health, education, and the energy transition will be crucial for sustaining long-term growth prospects.

Strengthened international cooperation is needed to achieve full growth potential

The world economy stands at a crossroads of intersecting challenges and opportunities. While some worst-case scenarios have been avoided, global economic growth has never fully returned to the pre-pandemic average of 3.2 per cent. Least developed countries and other vulnerable economies often remain trapped below their pre-pandemic trend growth levels, insufficient to significantly raise per capita incomes, eradicate poverty, or accelerate progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals. The urgent need for stronger and more effective global cooperation—to foster economic growth, accelerate the energy transition, and tackle global inequalities—has never been clearer. Multilateral efforts are also essential to ease the debt servicing burdens of many developing economies, expand access to concessional financing, and facilitate debt restructuring.

To strengthen international cooperation, the global community must address power imbalances, revitalize multilateral institutions, and ensure the equitable distribution of the benefits of new technologies. International efforts should prioritize leveraging technology to address the climate crisis and rebuild trust among nations and within societies. While challenges persist, recent agreements and initiatives such as the Summit of the Future in September 2024, and upcoming opportunities in 2025, including the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development, offer a platform for renewed global solidarity.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations