Diverging inflation rates suggest new risks

Diverging inflation rates suggest new risks

Global inflation trends

While an increasing number of countries are reopening their economies during the COVID-19 pandemic, the prospects of the world economy remain highly uncertain. One of the many uncertainties that the world economy is facing is the prospect of consumer prices.

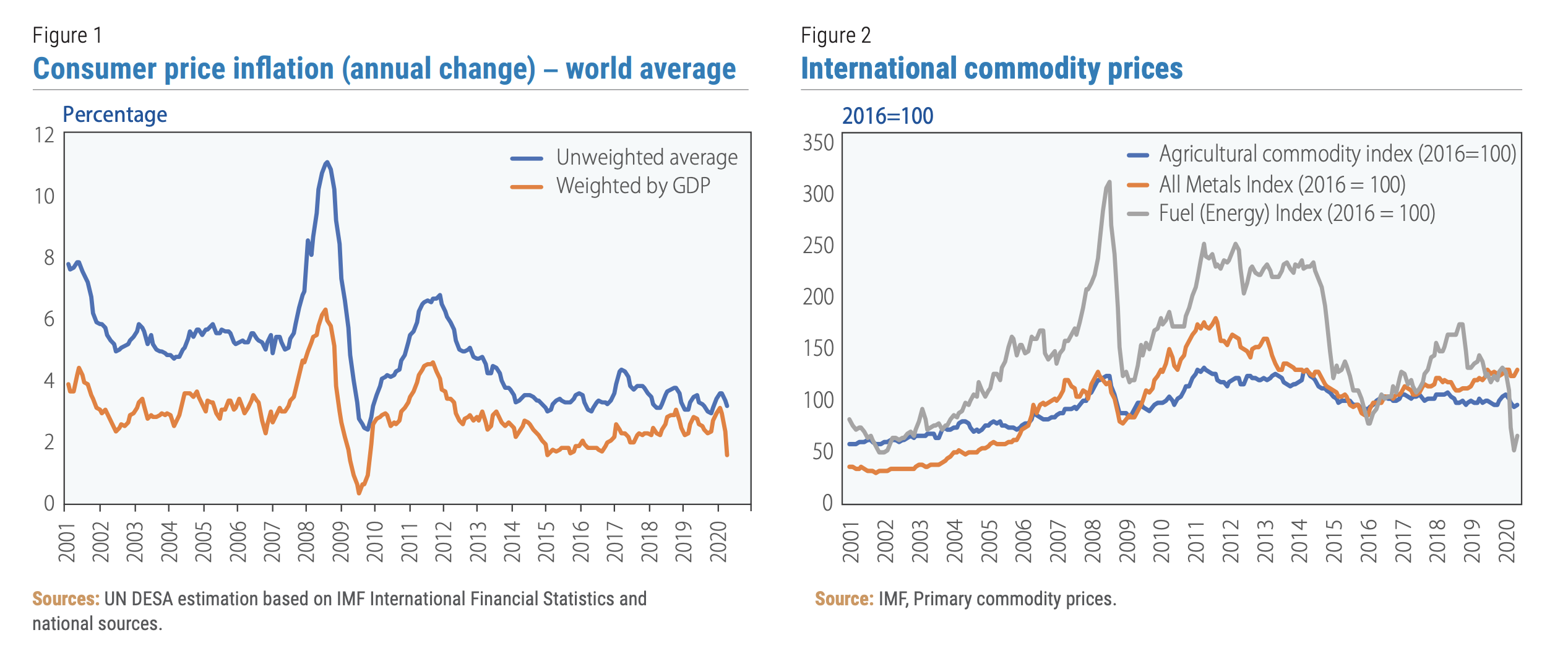

Before the COVID-19 pandemic hit the world economy, the global average trend pointed to a historically low level of consumer inflation (figure 1). The converging unweighted and GDP-weighted world average inflation rates implies the trend was observed not only in high-income countries. Several factors contributed to this trend. First, the supply capacity for consumers had been increasing, expanding globally through technological progress and world trade. Second, globalization-induced competition exerted downward pressure on the price of goods and services. Third, in some countries, the growth of wages has been insufficient to drive consumer price increases, despite the gains in productivity, due in part to the weakening of the institutions of collective bargaining, though this trend was not uniform across countries. Fourth, ?asset price inflation? reduced pressures on consumer price inflation. As indicated by the diverging asset prices and consumer prices, this trend appears more prevalent in countries after the global financial crisis of 2008. While the US Federal Reserve, the Bank of Japan, the Bank of England, and the European Central Bank struggled to raise the rate of inflation to the target 2 per cent, the combination of monetary easing and extremely low policy interest rates has buoyed the prices of financial assets over the last decade.

A spike in inflation rates took place globally in 2007 and 2011, primarily driven by the hike in international commodity prices, including food, energy and metals. Since 2015, commodity prices, except for a few exceptions such as palladium, have remained lower than the past peak. (figure 2).

A spike in inflation rates took place globally in 2007 and 2011, primarily driven by the hike in international commodity prices, including food, energy and metals. Since 2015, commodity prices, except for a few exceptions such as palladium, have remained lower than the past peak. (figure 2).

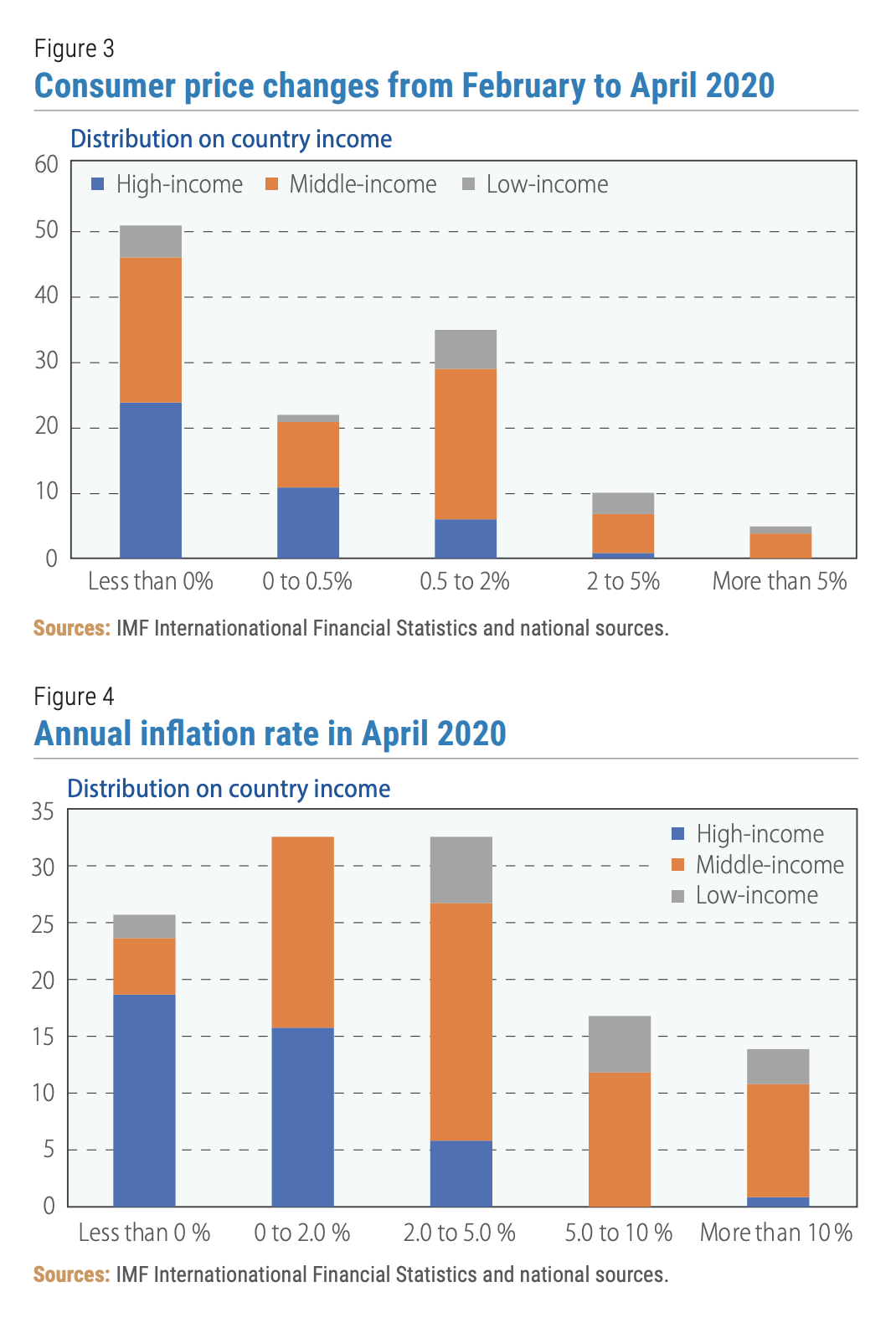

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the recent global trend of disinflation (figure 1). The GDP-weighted average annual inflation rate plunged from 3 per cent in February to 1.6 per cent in April. The unweighted world average inflation rate also weakened from 3.6 per cent in February to 3.2 per cent in April. The supply constraints caused by the disruption of supply chains so far have not given rise to significant inflationary pressures as a global trend. Meanwhile, the abrupt decline in the aggregate demand worldwide brought on by the containment measures implemented to halt the spread of the virus (border closures, lockdowns and social distancing) drove the collapse of the prices of oil and fossil fuel-based energy to historic lows (figure 2), although the prices of agricultural commodities and metals have remained relatively stable in international commodity markets.

Diverging inflation rates among countries The difference between the GDP-weighted world average inflation rate and the unweighted average world inflation rate during February and April implies diverging inflation rates among countries. The majority of countries, mostly of middle- and low-income, have been experiencing rising consumer prices since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Among 123 countries where the data are available for April 2020, consumer prices have increased in 72 countries (figure 3) between February and April?by more than 2 per cent overall in 15 of these countries. By contrast, consumer prices declined over two months since February in 51 other countries. In April, 26 countries experienced negative annual inflation rate (figure 4)?19 high-income countries, 5 middle-income countries, and 2 low-income countries. Of the 33 countries which registered an annual inflation rate between 0 per cent to 2 per cent, 16 are high-income countries, and 17 are middle-income countries. Among 31 countries which registered an annual inflation rate of more than 5 per cent, one country is a high-income country, 27 are middle-income countries, and 8 are low-income countries.

Diverging inflation rates among countries The difference between the GDP-weighted world average inflation rate and the unweighted average world inflation rate during February and April implies diverging inflation rates among countries. The majority of countries, mostly of middle- and low-income, have been experiencing rising consumer prices since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Among 123 countries where the data are available for April 2020, consumer prices have increased in 72 countries (figure 3) between February and April?by more than 2 per cent overall in 15 of these countries. By contrast, consumer prices declined over two months since February in 51 other countries. In April, 26 countries experienced negative annual inflation rate (figure 4)?19 high-income countries, 5 middle-income countries, and 2 low-income countries. Of the 33 countries which registered an annual inflation rate between 0 per cent to 2 per cent, 16 are high-income countries, and 17 are middle-income countries. Among 31 countries which registered an annual inflation rate of more than 5 per cent, one country is a high-income country, 27 are middle-income countries, and 8 are low-income countries.

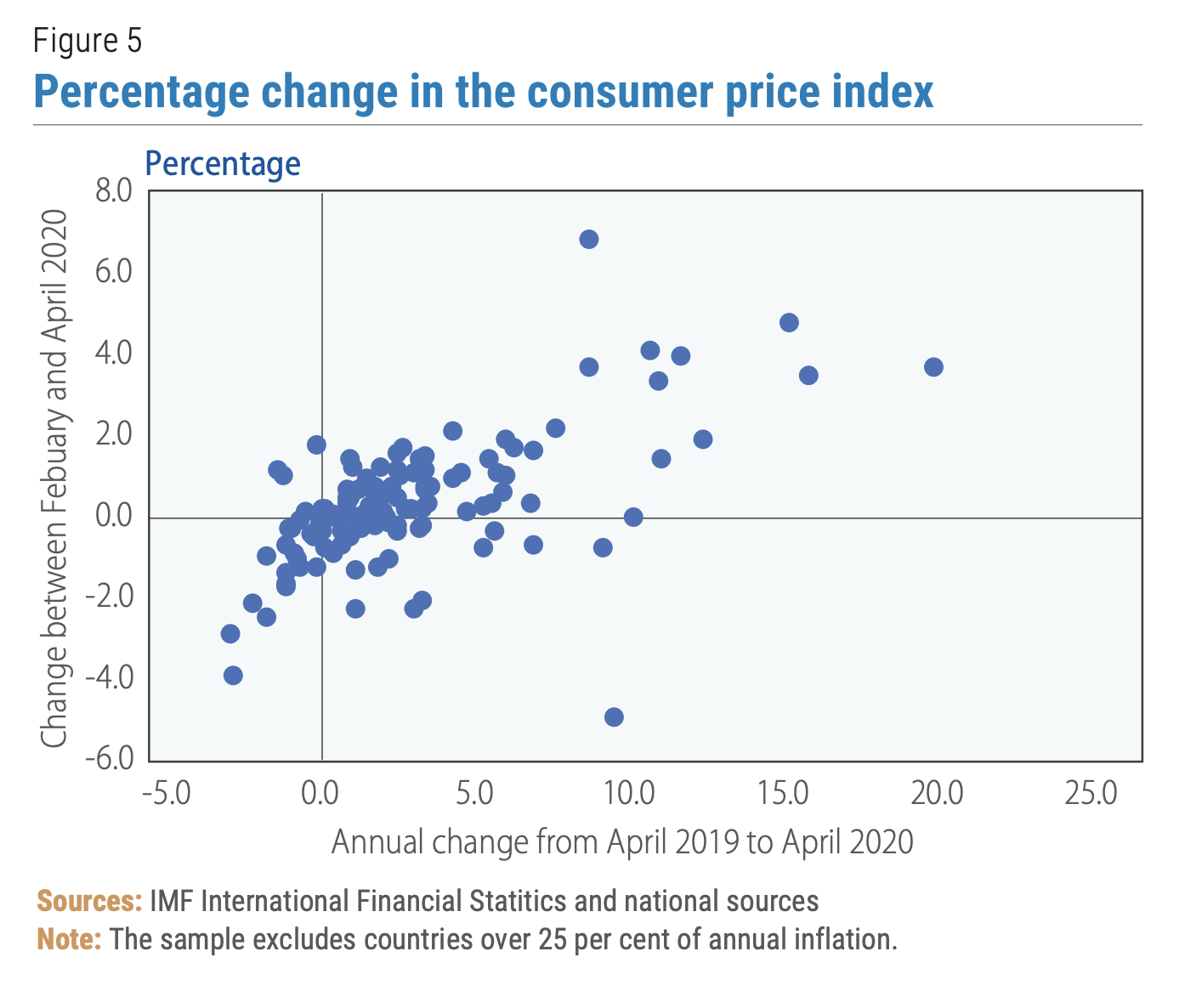

Disinflation since February has tended to appear in the countries which have already been experiencing low inflation rates for over a year (figure 5). For countries already on high inflation paths, the price level has tended to continue to rise, despite the COVID-19 pandemic. The high inflation situation is particularly noticeable in nine countries: Argentina, Iran, Lebanon, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of), Yemen and Zimbabwe.

Factors driving the diverging inflation rates

Factors driving the diverging inflation rates

Three main factors could be seen to have driven the diverging inflation rates among countries during the period since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic:

Different consumption patterns

Consumer price dynamics vary among countries, reflecting country-specific factors, although the episode of the last global spike in consumer prices indicates that international commodity prices are highly influential. For those countries experiencing a price decline during the current global pandemic crisis, the consumer price dynamics reflect the plunge in international energy prices and the relatively stable price of food items (figure 2). In other words, the recent price level of those countries was determined by the extent of energy price decline against other expenditure items, particularly food.

For example, in the United States, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) declined 0.1 per cent in May, compared to April. It marked the third consecutive month-to-month decline since March. While the price of energy items fell 18.9 per cent, the price of food items increased by 4.0 per cent. Compared to May 2019, the CPI increased by 0.1 per cent. In China, the CPI declined 0.8 per cent in May, compared to April. As in the case of the United States, it was the third consecutive month-to-month decline since March. Compared to May 2019, the CPI increased by 2.4 per cent. On a year-on-year basis, the price of food items increased by 8.5 per cent, which drove the general inflation trend. Despite the plunge in international oil prices, the price of transportation and communication, which include gasoline, declined only by 5.1 per cent.

Some countries have been observing varying degrees of rising domestic price for food items, despite the relative stability of international prices for agricultural commodities (figure 2), in part reflecting supply disruptions due to COVID-19. The rising food price has more influence in middle- and low-income countries since an average consumer in those countries spend a larger proportion of the income on food than an average consumer in high-income countries?the weight of food in the overall CPI is over 50 per cent in many of these countries, compared with only at 14 per cent in the United States. The weight for energy is usually lower in low- and middle-income countries than in high-income countries. Therefore, the impact of a drastic fall in the energy price can be much more limited for an average consumer in middle- and low-income countries to offset the rising price of food items.

Balance-of-payments constraints

Balance-of-payments constraints

From the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic, several countries have been experiencing higher inflation due to the rising price of imports, driven by tightening balance-of-payments constraints, impacted by international financial market volatility.

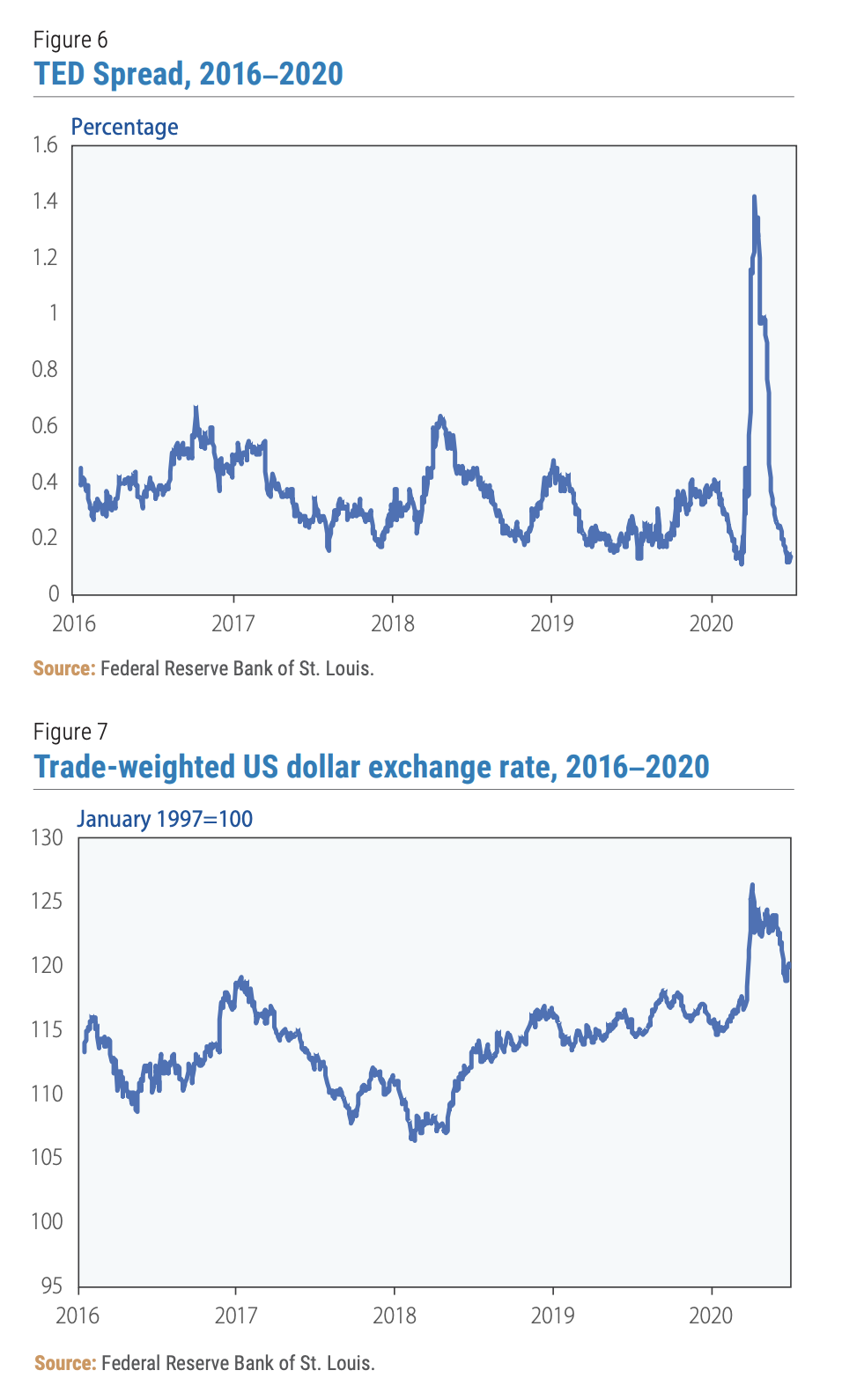

US dollar money markets came under extreme strain in March and April due to the abrupt rise in uncertainty over financial market prospects. The tightening US dollar funding market constraints met a surge in US-dollar liquidity needs (figure 6), driving a sharp increase during mid-March to mid-April in the TED spread, which indicates the funding constraint in the US dollar money market. The impact of the strained US dollar money markets was felt in the banking sector globally. A severe liquidity shortage was averted by the US Federal Reserve?s liquidity measures through the central bank liquidity swaps. However, reflecting the surge in US-dollar funding demand, the trade-weighted US dollar appreciated against the currencies of the major trading partners (figure 7). The situation created a pressure of currency devaluation for those countries that use the US dollar exchange rate as a nominal anchor to stabilize the price level.

Several countries were able to maintain the exchange rate against devaluation pressures by utilizing foreign reserves, and preserved price stability. For example, Egypt lost 20 per cent of foreign reserves from March to May 2020 ($ 9 billion) to defend the Egyptian pound. The CPI decreased by 0.1 per cent in May from April. On a year-on-year basis, the CPI for all items increased by 4.7 per cent in May 2020, which is a historical low for the country.

However, other countries could not stabilize the exchange rate against the US dollar. For example, in Turkey, the Turkish lira has depreciated against the US dollar by 9.3 per cent since March, which created pressures on domestic prices despite the weakening domestic demand in the current situation. The CPI for all items increased by 1.4 per cent in May from April. On a year-on-year basis, the CPI for all items increased by 11.4 per cent in May 2020.

The global US dollar liquidity crunch exacerbated Lebanon?s already severely tight balance-of- payments constraint. Although the Lebanese lira is still officially pegged to the US dollar at LL1507/$, the currency was most recently traded at LL3860/$ in licensed money exchanges. As the country is heavily reliant on imports for its essential goods, including food, fuels and medical supplies, the steep devaluation of the national currency resulted in a rapid rise in the consumer price. The CPI for all items increased by 6.9 per cent in May from April, after a 25.4 per cent increase from March to April. On a year-on-year basis, the CPI for all items increased by 56.5 per cent in May 2020.

Monetization of fiscal deficits

The monetization of fiscal deficits often impact inflation, and for this reason is usually prohibited by the statutory law of a central bank. However, a strong pressure for monetizing emerges when the country?s fiscal revenue base shrinks, particularly when the government?s ability to borrow domestically or abroad is constrained by high levels of debt. The COVID-19 pandemic has created this situation in many developing countries, where the growing needs for extraordinary public health spending and economic support measures is driving a further deterioration in the public finance situation, even as the public debt approaches what is generally considered to be unsustainable levels.

Do diverging inflation rates point to polarizing inflation trends?

The possibility of deflation in high-income and some middle-income countries and also the likelihood of further tightening of the balance-of-payments constraints in middle- and low-income countries will determine the trajectory and extent of divergence in inflation rates. There are, however, concerns that high-income countries may face higher inflation, not deflation, in the near term. The unprecedented level of economic responses leaves most governments with a higher level of debt. If the government?s debt issuance is excessive, it may crowd out private investments by raising funding costs. A higher nominal interest rate creates a high inflation expectation. Moreover, since major central banks have been injecting extraordinarily large amounts of liquidity in the effort to stabilize financial markets, their enlarged balance sheets may trigger a rapid expansion of broad money stock, which could raise inflation if the velocity of money remains stable.

However, the majority views agree that the demand for goods and services will likely remain subdued for the coming years. Consumer confidence in many countries has been shattered by the COVID-19 pandemic and the mitigation measures, including travel restrictions. Moreover, facing an unprecedented high level of economic uncertainty, many consumers are likely to increase precautionary savings. The household savings rate in the United States, for example, increased from 7.7 per cent in December 2019 to 23.2 per cent in May 2020. The European Commission forecasts that the household savings rate in the Euro area will increase from 12.8 per cent in 2019 to 19 per cent in 2020.

As much as high inflation is a significant risk factor for an economy, deflation is also a serious risk to an economy. The risk of inflation is intuitively understood. If the price of goods and services increases rapidly, income growth often cannot catch up with the rising prices. The resulting decline in real income impoverishes consumers. A prolonged inflationary expectation may hamper investments as real returns on the investments are often difficult to gauge. Intuitively, a declining price level implies an increase in real income. However, as the recent example of Japan shows, in a deflationary spiral, the economy shrinks in nominal terms. Under deflation, nominal wages may decline faster than the consumer price, which impoverishes consumers. Deflation increases the value of debt in real terms, which discourages investments on credit. Deflation also discourages consumer spending, as rational households expect prices to fall further and the economy falls into a liquidity trap. In both cases of high inflation and deflation, the economy slipped into a lower growth path.

The further tightening of balance-of-payments constraints is also uncertain. As the US dollar liquidity crunch has subsided (figure 6), the balance-of-payments constraint has also eased as the trade-weighted US dollar depreciated (figure 7). However, as the global COVID-19 crisis continues, international financial markets, including the US dollar money market, will remain susceptible to unexpected shocks. The countries under balance-of-payments constraints are likely to be promptly impacted by those shocks. Further into the future, structural improvements in this condition for countries under balance-of-payments constraints need a robust recovery in exports, an increase in capital inflows in the form of equity such as foreign direct investments, and effective external debt reliefs.

Policy implications to the polarizing inflation trends scenario

The divergence of inflation trends will likely contribute to keeping the world economy on a low-growth path. Investments are discouraged by deflation in high-income countries. Investments are also discouraged in the countries under balance-of-payments constraints for a widening funding gap for imports that are essential for investments. Consumers are impoverished by declining real wages, either by deflation in high-income countries or high inflation in countries under external constraints.

Moreover, the difference between deflation and high inflation paths could have significantly adverse distributional impacts?it could lead to a greater divergence in income growth and higher levels of inequality among countries. Given the high uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic, including the possibility of second and third-wave outbreaks, the stimulus measures in high-income countries may be accompanied with increased precautionary savings in both households and businesses.7 Given the current risk sensitivity, the excess savings are likely to seek safer asset classes, such as Government bonds in high-income countries?the higher sensitivity to risk may also imply lower private capital flows into middle- and low-income countries. While countries under deflation may experience excess precautionary savings, countries under balance-of-payments constraints may need to increase savings to service external debts for their growing values in local currencies. To avoid the polarization scenario, a set of well-coordinated policies would be needed to unlock the excess savings currently held in Government bonds as in high-income countries and channel these resources to middle- and low-income countries.

In the meantime, structural external resilience of middle- and low-income countries must be strengthened by promoting exports, foreign direct investment and external debt relief. Already, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and other multilateral development banks stepped up their lending activities considerably to support to middle- and low-income countries through emergency financing facilities, concessional financing and debt relief. However, the prolonged uncertainty of the COVID-19 crisis may require a more decisive cooperation initiative of the international community to prevent the polarization scenario from becoming a reality.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations