Tariff shocks and graduation

from the least developed country category

Background

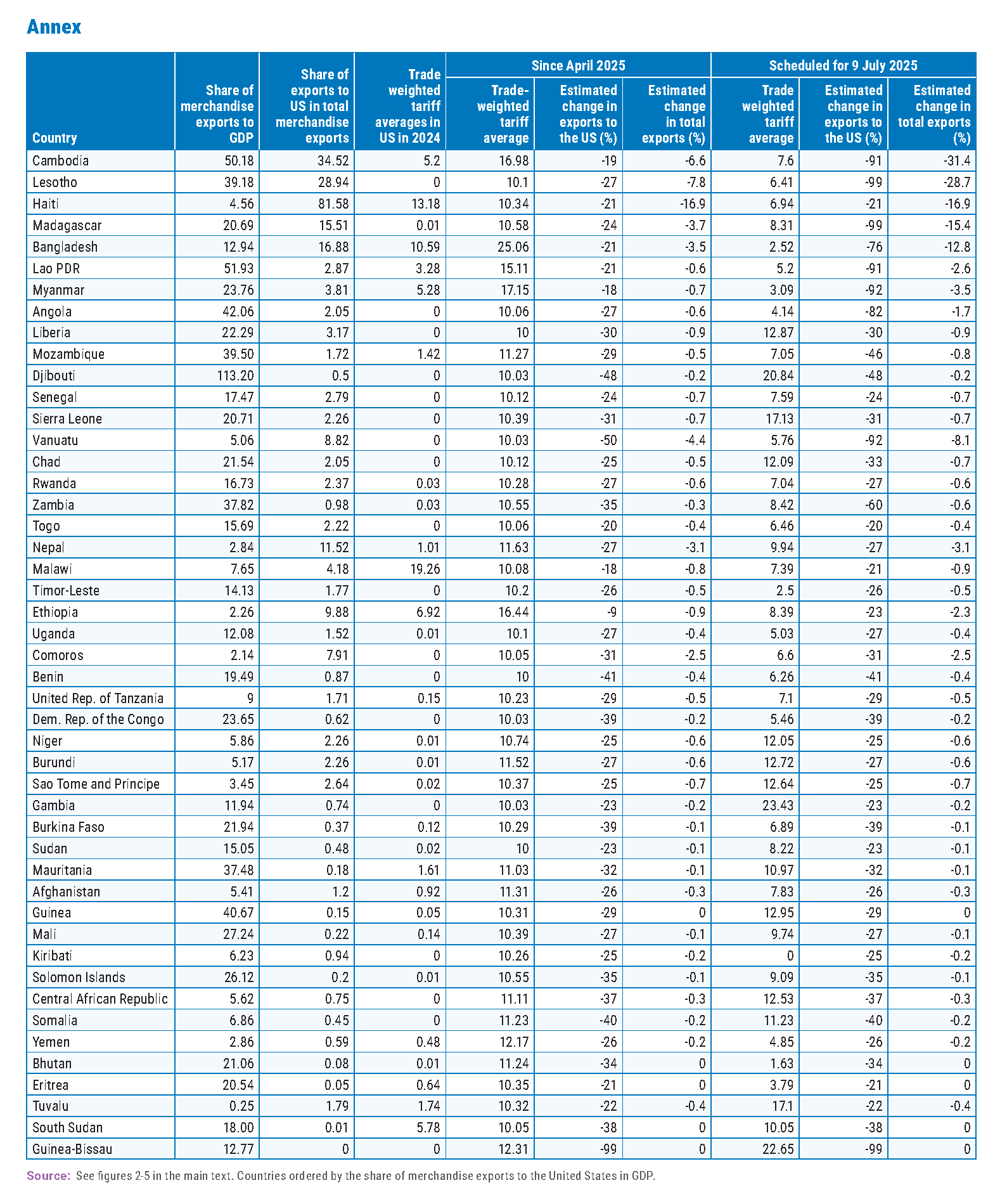

The Least Developed Countries (LDCs) category was created by the United Nations in 1971 to focus attention on a subset of developing countries that faced greater challenges to progress based on a multi-dimensional assessment. Membership in this category is reviewed triennially by an expert body of the United Nations, the Committee for Development Policy (CDP), which makes recommendations on graduation or inclusion based on development progress assessed against three criteria—per capita income, an index of human assets, and a vulnerability index encompassing environmental and economic risks —along with additional country-specific information and analysis. Figure 1 summarizes information on the current state of graduation from the LDC category.

International support to LDCs, intended to facilitate their graduation from the category, has sought to strengthen their integration into the global economy. Support has come from preferential market access, flexibility within World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements, preferences in the allocation and modalities of official development assistance, access to (a limited number of) LDC-specific funds and mechanism, and assistance for participation in international forums.

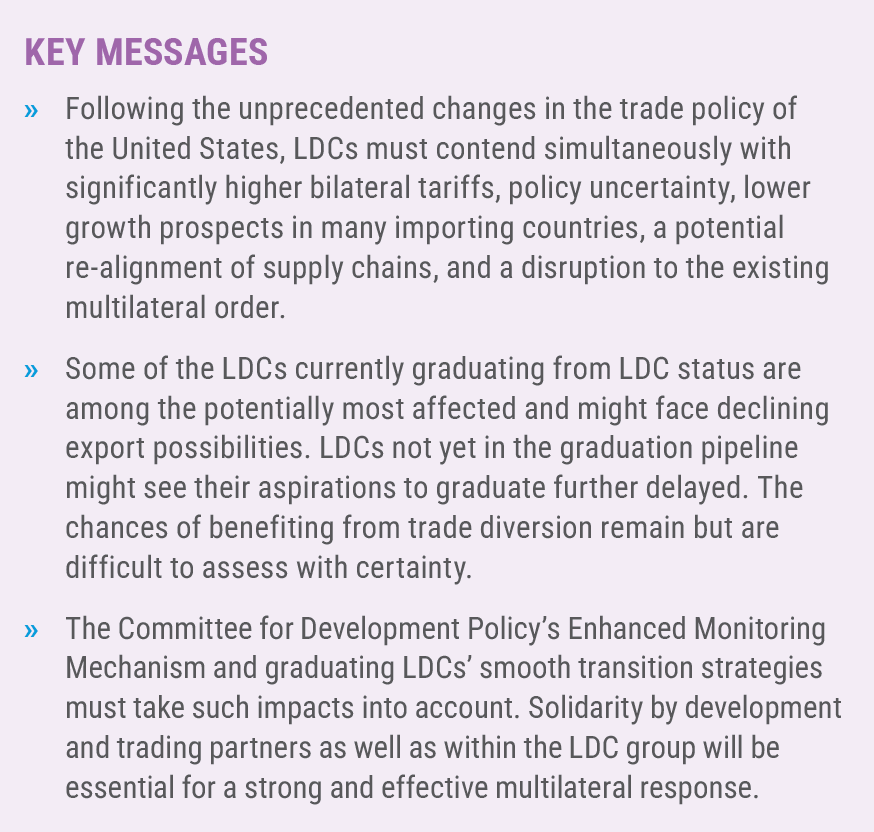

With trade-related measures being a vital component of such support, the unprecedented shock to established trading relationships from the unilateral escalation of United States tariffs announced in April 2025 have raised significant concerns about LDCs’ development and graduation prospects. Aside from the tariff rates themselves—with some of the highest placed on LDCs—selective temporary suspensions and bilateral negotiations have injected uncertainty, in itself a source of additional adverse impacts. As of May 2025, the average effective United States tariff rate was estimated to be around six times higher than the 2.5 per cent of early 2025, and policy uncertainty as well as market volatility have been simultaneously at unprecedented highs. Following the escalation, LDCs face a range of tariffs—from a floor of 10 per cent, to over 50 per cent, albeit some of these have been stayed until 9 July 2025 to allow for negotiated reductions.

With trade considered as vital for LDCs’ development progress, this Monthly Briefing reviews the possible impacts of the current tariff shock on LDCs, with a focus on their graduation. It first examines the role of trade in LDC graduation, followed by the importance of the United States as destination for LDC exports. It then reviews the potential impacts of the announced tariffs on LDC exports, as well as broader impacts on these economies. The Monthly Briefing concludes by reviewing policy options for a way forward.

The role of trade in LDC graduation

Since the creation of the LDC category, trade-related support has aimed to increase the demand for products exported by the LDCs. Consequently, duty-free quota-free (DFQF) access to the markets of developed and major developing countries has been the most prominent international support measure. More than $70 billion worth of LDC merchandise exports benefitted from LDC-specific DFQF market schemes in 2022, marking substantial, albeit incomplete, progress towards international commitments such as those expressed at the WTO or the Sustainable Development Goals.

Participation in the global economy has been essential for LDC graduation. It has enabled these countries to expand economic activities, thereby boosting income levels towards the income threshold for graduation. Improved integration provides resources as well as incentives for investments in health and education, enabling countries to progress towards meeting the human assets criterion. When integration allows for the export of a more varied set of products and access to a diversified set of markets, it also helps reduce economic vulnerability. Taken together, a robust integration into the global economy facilitates progress along all three LDC graduation criteria.

Other benefits include the provision of foreign reserves, critical for meeting import needs that can be substantial given the low productive capacity of LDCs. Merchandise trade, whether for low-skilled, labour-intensive manufacturing or commodities, has been an important form of integration into the global economy for many LDCs, particularly those in advanced stages of graduation.

At the same time, several other LDCs have benefited from the export of services, such as tourism; receiving remittances from migrant workers; or generating revenues through licenses for natural resource exploitation by foreign firms. These countries are typically less affected by adverse tariffs shocks than those highly reliant on merchandise exports.

Overall, the share of LDCs in world merchandise exports is still only slightly above 1 per cent, though it has more than doubled between 2000 and 2023. The share of LDCs in services trade is even smaller with 0.6 per cent in 2023 and shows a lower growth rate. Notably, the six graduating LDCs experienced a considerably faster growth rate of 158 per cent since 2000, so that they now account for 37 per cent of all LDC merchandise exports. Such associations underscore both the importance of trade-related support, as well as raising the question of what may be needed to allow more LDCs to benefit, an area of active investigation by CDP.

The United States as an LDC export destination

Overall, the United States is the third largest market for LDCs with a share of 8.4 per cent of their total exports. It ranks behind the European Union (20.1 per cent) and China (18.9 per cent), but ahead of the United Arab Emirates (7.8 per cent) and India (6.8 per cent). In 2023, the latest year for which complete data is available, the United States was the largest market for the exports of only two LDCs (Cambodia and Haiti). China is the largest market for 12 LDCs, the United Arab Emirates for 10 and the European Union for 7.

Overall, the United States is the third largest market for LDCs with a share of 8.4 per cent of their total exports. It ranks behind the European Union (20.1 per cent) and China (18.9 per cent), but ahead of the United Arab Emirates (7.8 per cent) and India (6.8 per cent). In 2023, the latest year for which complete data is available, the United States was the largest market for the exports of only two LDCs (Cambodia and Haiti). China is the largest market for 12 LDCs, the United Arab Emirates for 10 and the European Union for 7.

This pattern is partly due to the dominance of commodities in many LDCs’ exports, for which developing countries are key markets. Moreover, garments, the main sector of manufacture-exporting LDCs, has been excluded from the preferential trade agreements offered by the United States to all developing countries, though it is covered by the specific preferential scheme for African countries (AGOA). Hence, Asian LDCs face more difficult market access conditions in the United States than in other developed countries, leading to smaller market shares.

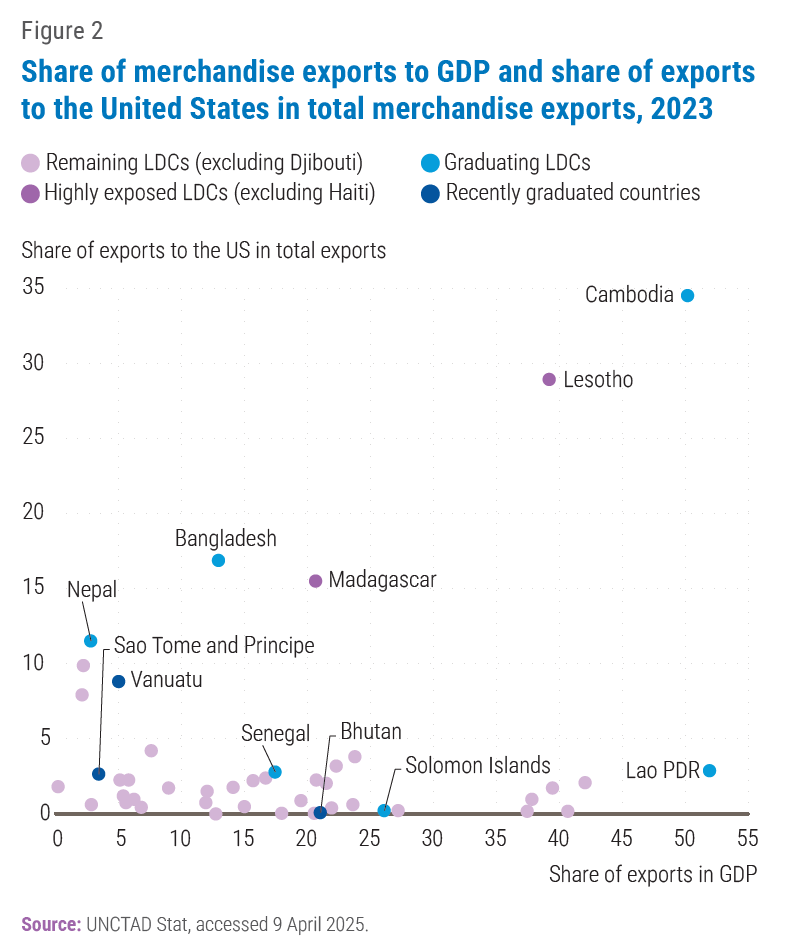

The share of merchandise exports in gross domestic product (GDP) and the share of exports to the United States in all merchandise exports together provide an indication of the exposure to changes in United States trade policy. Figure 2 shows these ratios for all LDCs and the three most recently graduated countries in the year 2023. The figure excludes Haiti and Djibouti for better visibility, as they would be far out in the upper left and lower right corner, respectively. The table in the annex contains the corresponding data for all LDCs and countries that have graduated recently.

The figure reveals notable differences between countries. Among graduating LDCs in particular, Cambodia is the most directly exposed, due to both its overall export dependence and the prominent role of the United States market. Bangladesh and Lao PDR are also exposed quite significantly, the former due to the relatively large share of exports to the United States and the latter due to its overall trade dependence. The remaining three graduating countries are somewhat less exposed: merchandise exports play a small role for Nepal, while Senegal and Solomon Islands mainly serve other markets.

All three recently graduated countries have low exposure: Sao Tome and Principe and Vanuatu mostly export tourism services rather than merchandise, whereas Bhutan relies predominantly on India as its export market. Among other LDCs, Lesotho, Haiti and Madagascar are particularly exposed. Overall, the figure underscores the heterogeneity among LDCs, both with regard to the importance of merchandise trade for economic development and export market concentration.

Graduating and recently graduated countries often see expansion into the United States market as one of the ways to mitigate the impacts of losing LDC-specific market access arrangements after graduation. Analysis has shown that for LDCs in Asia, graduation does not significantly impact market access to the United States, whereas major providers of LDC-specific DFQF schemes such as the European Union, India, China, United Kingdom, or Japan withdraw access to these schemes (some immediately after graduation; several after a transition period of typically three years). Hence, exporting to those countries often becomes costlier for LDCs at some point after graduation, though in some cases they may have access to alternative duty-free regimes.

New tariffs faced by LDCs

The potential impact of tariff increases depends on both the relative exposure of a country to the United States market and on the actual hike in United States rates. The decision announced on 2 April 2025 brought rates up by 10 percentage points for all countries, with an additional amount proportional to the size of the United States bilateral merchandise trade deficit with each individual country. Average tariffs would increase to levels not seen for over a century. Subsequently, on April 9, tariff increases beyond 10 per cent were paused for 90 days, while tariff rates for China were raised to 145 per cent for most goods, though these were subsequently reduced to 30 per cent. Separately, product-specific tariffs—such as for steel, aluminium and automobiles—were also announced.

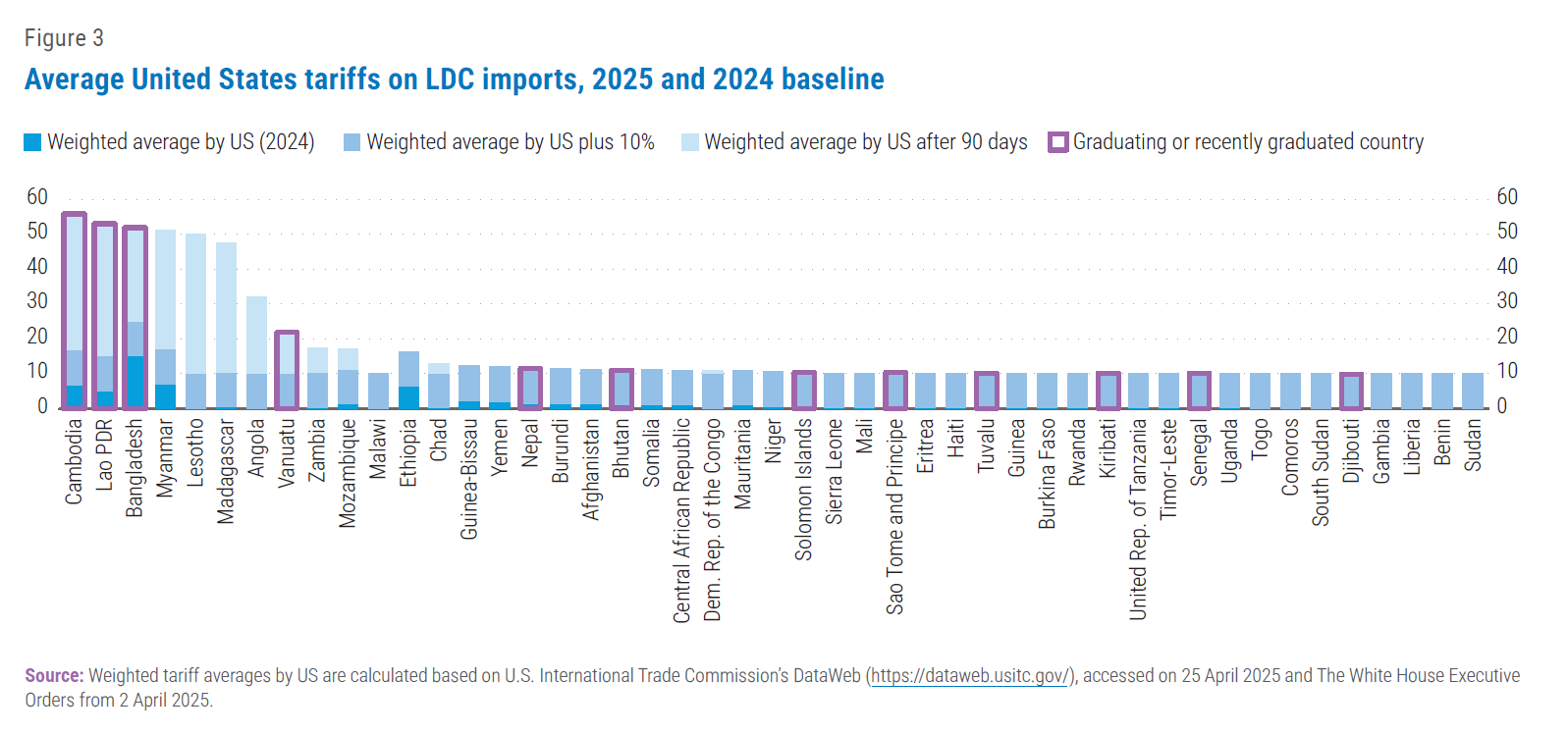

Figure 3 shows the effective average tariffs imposed by the United States on LDCs. The dark blue bar shows tariffs in place in 2024, the medium blue bars the 10 percentage points uniform increase currently in place, and the light blue bars the additional increases for 12 LDCs scheduled to be in place from 9 July 2025. The corresponding numbers are contained in the table in the annex.

Notably, in 2024, most LDCs faced an average effective rate of zero, but several others, mostly in Asia, already faced relatively high tariff barriers. This was due to the fact that their major export to the United States was garments, which face relatively high tariffs and are excluded from preference schemes available to Asian LDCs. The figure illustrates the eventual scale of the tariff increases, including both the ‘universal’ 10 per cent hike, as well as those proportional to the merchandise trade deficit, currently in abeyance.

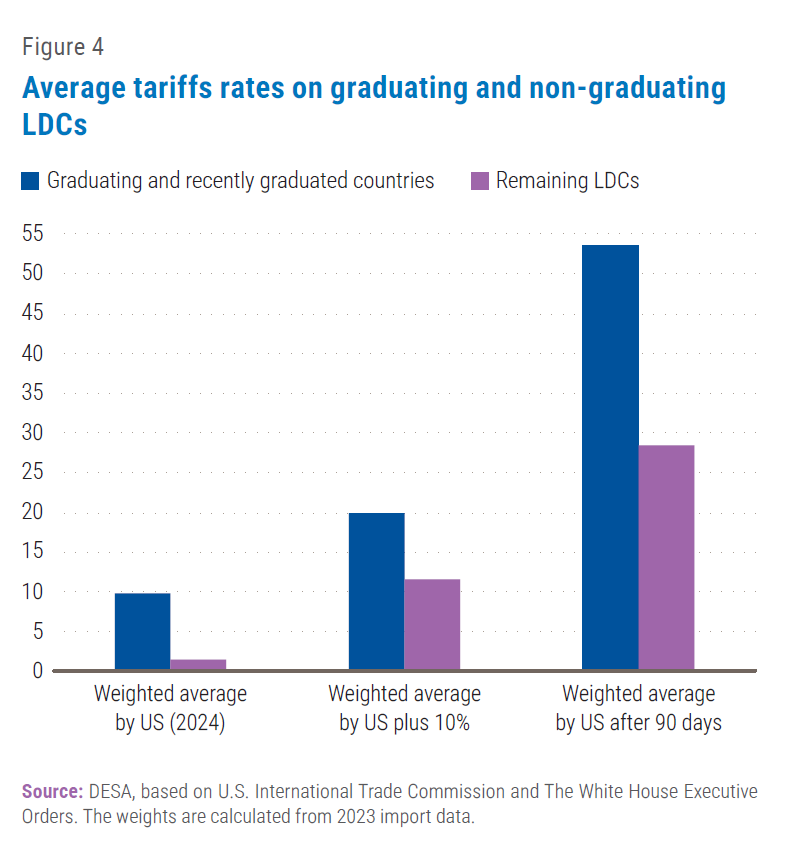

Consequently, graduating LDCs on average face higher United States tariffs than non-graduating LDCs (figure 4). The trade-weighted average of tariffs imposed on graduating LDCs would increase from a relatively high 9.8 per cent to 53.6 per cent if all announced tariffs were fully implemented, while for non-graduating LDCs it would increase from a relatively low 1.5 per cent to 28.4 per cent (see figure 4).

Effective tariff rates are especially high for those LDCs that have been relatively successful in leveraging existing systems of preference to develop low-skilled manufacturing as part of the structural transformation of their economies. These LDCs are mostly competitive in low-skilled labour-intensive manufacturing such as garments or footwear, which are no longer produced in large scale in developed countries. At the same time, these LDCs are still poor and have, therefore, limited demand for high-skilled manufactures typically exported by developed countries such as the United States.

Changes in relative tariff rates can redirect trade flows

LDCs faced with higher additional tariffs could also be impacted by changes in tariff rates compared to competitors. For example, in the garment sector, some competitors of LDCs, such as China and Viet Nam potentially face new tariff rates that are even higher than those faced by graduating LDCs. Should such differentials persist, garment exporting LDCs may find their products relatively competitive in the United States, although they would need to contend with Central American producers who may be facing lower rates. The net effect, though, remains unclear as the highest tariff increases are yet to be finalized, and businesses would find it difficult to invest in scaling up or moving production until there is some certainty.

Such trade diversion was observed in 2018 after the imposition of United States tariffs on Chinese-made solar cells and panels. Cambodia emerged as a significant exporter of these products, with its share in United States imports of these products rising from zero in 2017 to 9 per cent in 2023, while the share for China fell from 20 per cent to 2 per cent. Southeast Asian economies such as Viet Nam and Thailand saw even larger gains in market share. In its trade forecast from 16 April 2025, which assumes that the current pause of tariff increases beyond 10 per cent remains in place, the WTO increased its growth forecast for overall exports from LDCs from 3.5 to 4.8 per cent, highlighting the possibility of trade diversion in garments and electronics from China.

Such trade diversion was observed in 2018 after the imposition of United States tariffs on Chinese-made solar cells and panels. Cambodia emerged as a significant exporter of these products, with its share in United States imports of these products rising from zero in 2017 to 9 per cent in 2023, while the share for China fell from 20 per cent to 2 per cent. Southeast Asian economies such as Viet Nam and Thailand saw even larger gains in market share. In its trade forecast from 16 April 2025, which assumes that the current pause of tariff increases beyond 10 per cent remains in place, the WTO increased its growth forecast for overall exports from LDCs from 3.5 to 4.8 per cent, highlighting the possibility of trade diversion in garments and electronics from China.

While changes in relative tariff rates are just one of the factors behind this market dynamic, the experience from 2018 demonstrates that LDCs may benefit from rising tariffs imposed on competitors. However, the current uncertainty and the possibility of massive tariff increases on LDCs in the near future may limit or preclude trade diversion.

Overall impact of the tariff shock on LDC exports

Given the high uncertainty of the future trading landscape and the magnitude of the trade shock, estimating its impact on trade flows is difficult. However, figure 5 shows initial indicative estimates using a conventional modelling tool for direct impacts of the tariff increases on exports from LDCs to the United States. The results are broadly consistent with estimates based on partial equilibrium analysis provided by the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific of the United Nations.

According to these simulations, the 10 percentage point increase in tariffs would result in LDC exports to the United States decreasing by 21 per cent from the 2024 aggregate of around $24.4 billion. However, if the additional increases that are currently on hold were implemented, there could even be a decline as large as 77 per cent in the aggregate value. With a 10 percentage point increase, Bangladesh and Cambodia would see the largest absolute declines, of $1.8 billion and $1.6 billion, respectively. With the additional tariff increase, export from these two countries could decline by $6.7 billion and $7.7 billion, respectively.

The overall export performance of LDCs will depend not only on the reduced demand from the United States but also on possibilities to redirect exports to other countries. For example, the European Union partially suspended Cambodia from its DFQF-scheme in 2020. Subsequently, between 2019 and 2021, European Union imports from Cambodia in the garment and textile sector fell by 17 per cent (whereas competitors such as Bangladesh saw an increase of 6 per cent), before rebounding. However, imports by the United States from Cambodia increased by 39 per cent over the same period.

While there continues to be uncertainty about the eventual set of new tariffs, another risk looms large—the likelihood of non-renewal of US African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) beyond its current validity until September 2025. Currently, 20 of the 32 African LDCs have preferential access to the American market thanks to AGOA, for a variety of products including apparel. Some local industries, such as the textile industry in Lesotho, have grown largely thanks to the AGOA preferences. Non-renewal of AGOA would make all eligible African LDCs subject to most-favoured-nation (MFN) tariffs, as well as the additional tariffs (if enacted), limiting their competitive advantage.

Reduced exports from LDCs can have significant social consequences, increasing unemployment and poverty. There can also be a differential impact on women: for example, workers in the garment sector, the dominant export-oriented manufacturing sector in LDCs, tend to be mostly female, and a sharp fall in exports can significantly exacerbate gender inequality. Employment and poverty impacts can reverberate through the economy through a number of different channels.

Impacts beyond bilateral trade

Global trade

Apart from the effects on United States-LDC trade, the tariff increases and the attendant uncertainty are expected to slow growth prospects across the world. In May 2025, UN DESA reduced its forecast for global GDP growth in 2025 and 2026 by 0.4 percentage points each year. The two largest markets for LDCs, the European Union and China, are now expected to grow in 2025 by 1 per cent and 4.6 per cent, respectively, both below the average of the 2010s (1.6 per cent for the European Union and 7.7 per cent for China). Lower growth prospects can further dampen the demand for exports from LDCs by other countries.

Overall, the trade channel (combining the impacts on exports to the United States discussed in the previous sections and the impacts on exports to third countries discussed in this section) has the potential to impact current and future graduation processes, though impacts would be highly country-specific and difficult to predict. Some graduating countries might observe declining exports, even as growth prospects are diminished. An evolving global trade landscape may require additional adjustments to strategies for ensuring a smooth transition.

Investment

The negative impacts of tariff increases also affect domestic and foreign investment. The increased uncertainty on future market access conditions and global demand may generally delay or reduce investments in LDCs and other countries. The possibility of redirecting investments to other countries could also impact investments in LDCs positively or negatively. However, while some re-alignment in global supply chains happened during the trade tensions between the United States and China in 2018, with Cambodia emerging among a favoured destination of investments, such impacts may be more difficult to realize at the current juncture due to prolonged policy uncertainty.

Investment in LDCs may also be affected by a transmission of global interest rates. The inflationary impacts of tariffs can slow down the rate at which the Federal Reserve proceeds to reduce interest rates. While the possibility of a further slowing of the United States economy may impel the Federal Reserve to instead reduce rates, the ongoing interest rate uncertainty also dampens investments.

The impacts on trade and investment both have consequences for growth rates. UN DESA recently reduced its GDP growth forecasts for LDCs from 4.6 per cent in 2025 and 5.1 per cent in 2026 to 4.1 and 3.8 per cent, respectively, further below the agreed target of 7 per cent GDP growth in LDCs. For graduating and recently graduated countries that surpass the income graduation threshold, this could reduce resources to finance investment and social protection in support of graduation, while for non-graduating LDCs it may prolong the time needed to reach graduation thresholds.

Exchange rates

Exchange rates would be impacted by interest rate moves as well as trade policy. Standard trade theory implies that an increase in tariffs would lead to an appreciation of the United States dollar vis-à-vis impacted countries, as higher tariffs reduce the demand in the United States for imports from impacted countries and, thus, for non-United States currencies.

How exchange rates will react in the current situation, however, remains to be seen as exchange rate movements are also impacted by expectations of future economic growth, inflation, trade and investment flows (and hence future demand for foreign exchange). Importantly, unexpected market reactions to the tariff announcements have drawn attention to the bond market and the possible impacts to the role of the United States treasuries as a global safe haven, based on their perceived risk-free nature and the high liquidity of the treasuries market. In fact, the immediate reaction of exchange rates has been a depreciation of the dollar against most developed country currencies, defying standard trade theory, whereas bond yields rose contrary to earlier instances of instability in global financial markets.

However, exchange rate movements for LDCs have been mixed. During April and May, 16 LDCs experienced a slight depreciation against the dollar, while currency appreciation was most pronounced in LDCs whose currencies are effectively fixed vis-à-vis the Euro, such as the CFA francs in West and Central Africa.

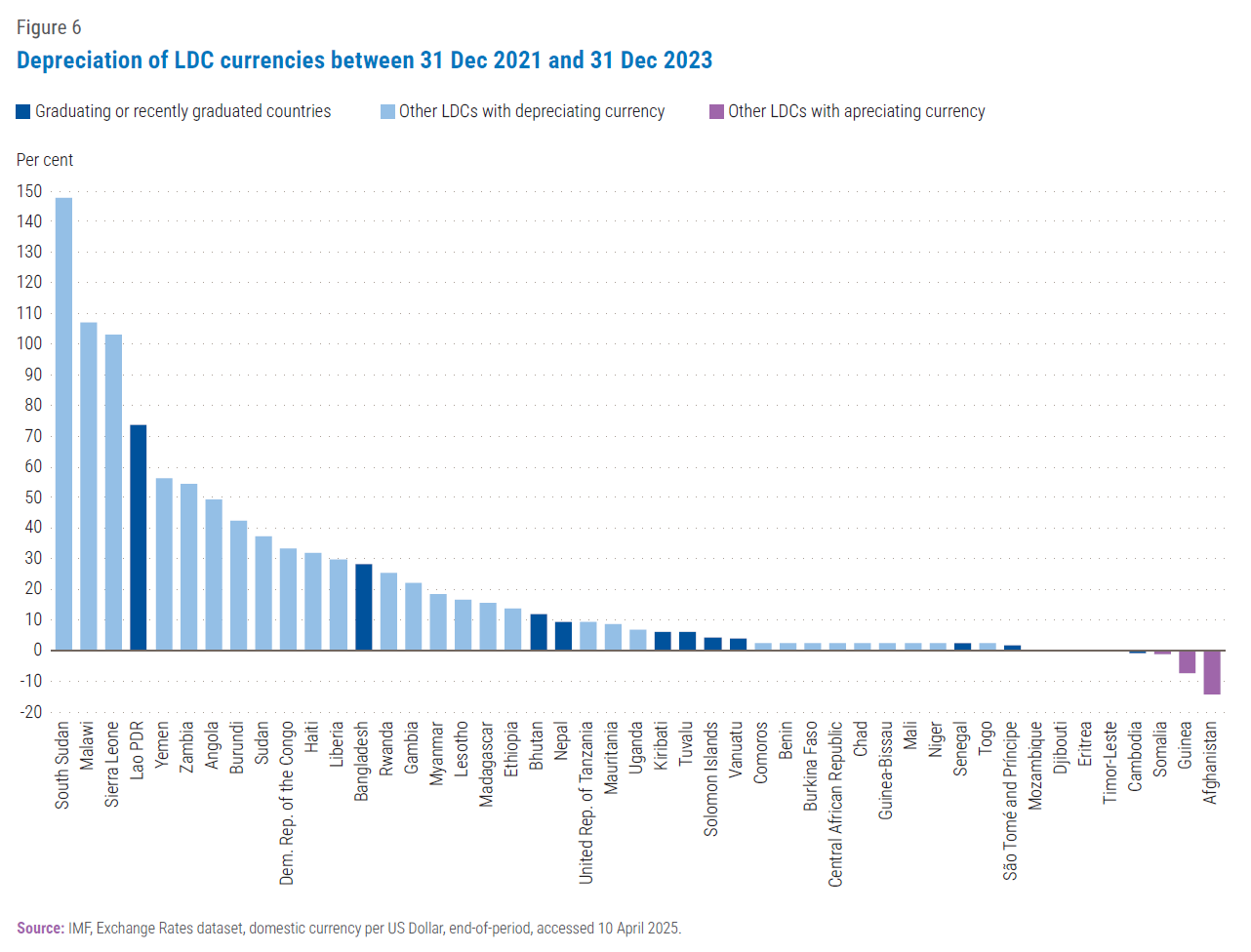

Several LDCs, including graduating countries, have faced significant currency depreciation in recent years, after the shocks caused by the war in Ukraine and global interest rate shocks, highlighting the importance of closely monitoring exchange rate developments. Over the 2022‒2023 period, eleven LDCs saw their currency depreciate by more than 30 per cent against the United States dollar (see figure 6). While depreciation can in principle have a positive impact on exports, negative impacts on the trade balance, inflation and debt payments dominated in most LDCs. Moreover, while the methodology used for determining the graduation income criterion smooths exchange rate variations, depreciation can still impact graduation eligibility, particularly when exchange rate shocks and growth shocks interact.

Between 2022 and 2024, country-level impacts of currency depreciations were particularly negative when they interacted with global price increases for oil and food. The immediate reaction after the tariff announcements in April had been a further drop in oil prices, while impacts on food prices are not yet discernible. As most LDCs are (net) oil importers, the reduction may, very partially, mitigate some of the negative impacts of the tariff shock. However, for oil exporting LDCs such as Angola, Chad or South Sudan, the decline in oil revenue would amplify negative impacts.

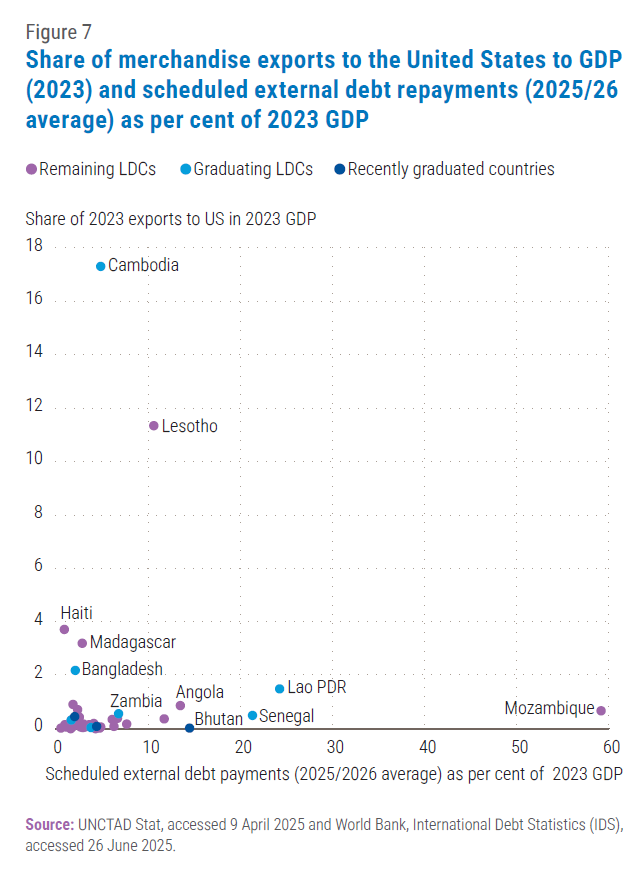

The financial transmission mechanism of the tariff shocks would be of particular concern for countries that face significant external debt repayment at a time of a significant decline in export earnings. Figure 7 shows upcoming scheduled external debt payments and the share of merchandise exports to the Unites States as rough measure for the exposure to the trade shock via the trade channel for all LDCs. The figure shows that LDCs facing particularly high external debt repayments, such as Senegal, Lao PDR and Mozambique, are less dependent on exports to the United States, while those that have the highest exposure to the tariff shock such as Cambodia or Lesotho face only moderate debt repayments. Further analysis would be needed as trade patterns shift, export earnings change, and a global growth slowdown imposes pressures on debt servicing.

Conclusion and ways forward

LDCs must contend simultaneously with bilateral tariff shocks, policy uncertainty, lower growth prospects in many importing countries, a potential re-alignment of supply chains, and a disruption to the existing multilateral order. These shocks come on top of an already tardy recovery from prior shocks of the past half-decade. At the same time, in many LDCs, challenges such as climate change impacts or armed conflicts are mounting.

LDC graduation prospects are impacted primarily through three channels. First, trade with both the United States and other partners is impacted. Impacts are country-specific, depending on future tariffs on both the LDC and its competitors, the importance of merchandise exports overall and of the United States market in particular. On average, graduating LDCs are affected more than LDCs that are not yet graduating. However, looking forward, effects can also be discerned on the prospects of several LDCs that are approaching the graduation pipeline. Second, the growth channel reduces the future income of LDCs, not only because of reduced exports but also because of increased uncertainty affecting economic activity more broadly, possibly further delaying future graduations. As a third channel, the reduced export earnings affect the balance of payments position of LDCs, possibly creating financial risks, especially for LDCs with high external debts.

The potentially grave impacts on the development pathways of LDCs, including those graduating from the LDC category, require close monitoring in the months and years ahead. That would include monitoring of tariffs and tariff margins, trade flows, and broader economic impacts. Such monitoring would be linked to the enhanced monitoring mechanism of graduating and recently graduated countries by the CDP, for which UN DESA acts as the secretariat. As a follow-up, graduating countries’ smooth transition strategies can be designed to mitigate such shocks.

The tariff shock underscores the importance of further diversifying export markets and accelerating structural transformation. Fostering regional cooperation, for example through the new African Continental Free Trade Area or a deepening of economic integration within existing free trade areas and other arrangements for economic cooperation, promises beneficial avenues for market diversification, with benefits accruing more in the medium- to long- term.

Supporting LDCs’ access to export markets could be achieved through further expansion of existing DFQF-schemes for LDCs. While product coverage of existing schemes has already improved, often almost or fully reaching 100 per cent of tariff lines, further liberalization of rules of origin could provide scope for additional preferential liberalization. Moreover, more developing countries could introduce LDC-specific DFQF schemes. Recognizing the growing importance of other channels such as remittances and trade in services, joint efforts could be made to strengthen the contribution of these sectors to LDC economies.

To pursue a collective approach, solidarity will be critical, both within LDCs and between LDCs and other countries and country groupings in various forums. Individually, even larger LDCs have only a marginal economic or political weight in the international arena. Hence, despite the heterogeneity among LDCs on trade issues, acting as a group and using their established group structures under the United Nations and WTO, would increase leverage in international discussions. Solidarity by other country groupings, particularly other developed countries and major developing countries, with the group of LDCs would be even more important. The longstanding understanding that support to LDCs is a common objective that is central to the multilateral system and advances shared objectives such as eradicating poverty and building resilience, should help anchor such solidarity.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations