- Is the zero lower bound no longer a hard constraint?

- EU-wide strategy to address refugee crisis remains elusive

- Drought leads to a spike in food prices in Africa and Latin America

Global issues

Widening divergences in global monetary policy stances

During the global financial crisis of 2008/09, the major central banks in the developed economies cut interest rates to near-zero levels. At that time, the zero lower bound on nominal interest rates was viewed as a hard constraint on monetary policy. This constraint was grounded in the premise that cash bears an implicit interest rate of zero per cent. The imposition of a negative rate?implying that the lender would pay the borrower for the privilege of lending them money?would simply result in massive cash withdrawals from the banking system, choking off credit and deepening the financial crisis. However, both Denmark and Sweden ventured slightly below the zero lower bound between 2009 and 2012, and, in 2014, the European Central Bank (ECB) became the first of the large-economy central banks to experiment with a negative interest-rate target.

Fears of the shift to a cash society have so far proven unfounded, and the zero lower bound is no longer viewed as a hard constraint by several monetary authorities. In January 2016, the Bank of Japan joined the ECB and the central banks of Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland in adopting a negative policy rate. Subsequently, the central bank of Sweden and the ECB have both cut policy rates further. At the same time, the United States Federal Reserve (Fed) has embarked on a gradual process of withdrawing monetary stimulus from the economy. This divergence in the monetary stance of the major central banks poses a policy dilemma for many monetary authorities in developing countries, triggering exchange-rate pressures and volatile capital flows. Since the Fed move in December 2015 to raise the target range for the federal funds rate by 25 basis points, a number of countries have increased policy rates (Angola, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Chile, Colombia, Egypt, Georgia, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) of China, Kazakhstan, Kuwait, Mexico, Mozambique, Namibia, Paraguay, Peru, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Tajikistan and the United Arab Emirates) while others have cut interest rates (Armenia, Bangladesh, Bulgaria, Indonesia, Moldova, Mongolia, Serbia and Taiwan Province of China) highlighting the growing divergence between rates of return at the global level.

The policy instrument that has been assigned a negative interest rate is primarily the deposit rate paid by commercial banks on some portion of their reserves held at the central bank. For the most part, commercial bank retail deposit and lending rates have remained positive, although corporate deposit rates in Denmark have been slightly negative since 2015. In addition, the market yield on a range of maturities of benchmark bonds is trading at negative interest rates, obscuring the fair value of relevant bonds

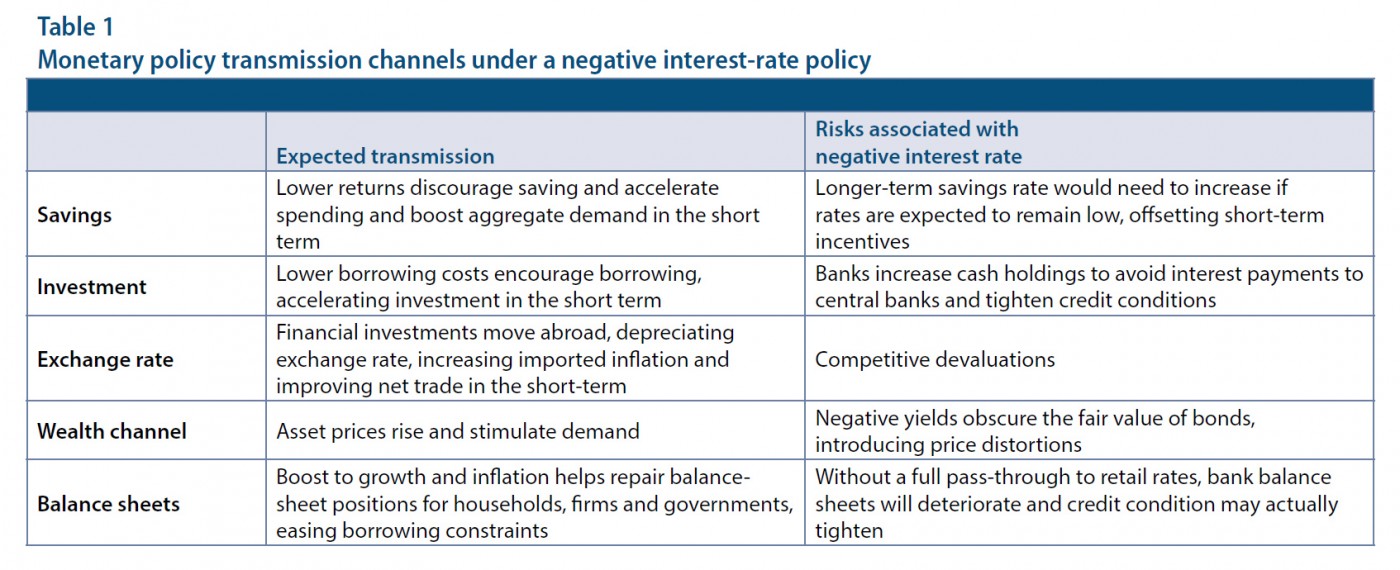

In principle, setting a negative policy interest rate operates in much the same way as any other interest-rate cut. The key transmission channels are detailed in table 1. In practice, a negative interest-rate policy bears certain idiosyncratic risks that may impede these channels of transmission. These risks can be expected to intensify over time and as rate cuts deepen.

One of the important risks associated with a negative

interest-rate policy is the squeeze on profit margins of financial institutions, heightening risk in the financial sector. Financial institutions rely on lending at higher rates than they borrow. As their central bank deposit rates drop below zero, there may be contractual or market constraints on the ability to pass these lower interest rates on to their customers. Institutions with inflexible long-term obligations, such as pension funds and insurance companies, are particularly at risk.

Thus far, the experience in Europe has seen retail deposit rates decline more or less in line with the declines in the central bank deposit rate, and credit conditions have generally eased. Nonetheless, share prices in the banking sector have dropped, which may indicate concerns about the future health of the banking system. There is reason to believe that retail deposit rates, especially for households, are likely to remain downwardly inflexible at about zero, dampening the transmission of further policy-rate cuts to the retail sector. In Japan, policy interest rates have been essentially zero since the 1990s, and retail deposit rates are already very low. This leaves little scope for passing on rate cuts to the retail sector without breaking the zero lower bound. The incentives for commercial banks to hold cash rather than pay interest on excess reserves held at the central bank can also be expected to increase over time. Increasing the stock of cash held by a bank entails a certain amount of set-up costs, in terms of storage, transportation and insurance. The longer the negative rates are expected to persist, and the higher the interest payments are on excess reserves in central banks, the more attractive investing in additional cash storage systems will become.

Small open economies, such as Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland, introduced a negative interest rate primarily to ease upward pressure on their exchange rate against the euro area, which is their biggest trading partner. As the policy becomes more widespread in larger economies, this raises concerns regarding "beggar-thy-neighbour" policies that lead to competitive devaluations among central banks, pushing rates further and further below zero despite the other financial risks attached to such moves. This may be particularly harmful in a global economy that remains characterized by subdued demand. While policy interest rates in most developing countries stand well above the zero lower bound, if economic prospects continue to deteriorate at the global level, more countries may also consider the option of introducing a negative interest rate policy. Those who do should use such a tool with caution, considering all of the risks to financial and economic stability that it may entail.

The migration situation in Europe

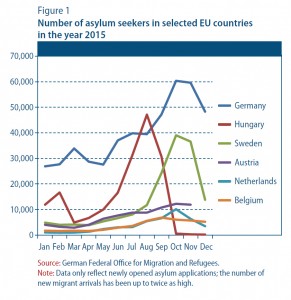

The migration situation remains a major challenge for Europe. Despite the winter season, several thousand migrants reach the borders of the passport-free-travel Schengen area each day, with many of them crossing the Aegean Sea from Turkey to Greece. A large number of migrants then travel on various routes through Europe in their attempt to reach countries such as Germany or Sweden, which registered the highest absolute numbers of new applications for asylum status within the European Union (EU) in 2015, with almost 480,000 and 165,000 cases, respectively (figure 1). The actual number of new arrivals in 2015 has been up to twice as high as applications due to the time lag between the first registration of migrants and the official opening of the asylum application process. According to recent trends, more than half of asylum seekers are from Syria, followed by Iraq and Afghanistan. For the month of January, Germany reported an up-tick in asylum applications compared to December, with 72 per cent of asylum seekers being younger than 30 years of age and 67 per cent being male.

The flow of migrants has created serious challenges both for the transit countries and the destination countries in Europe. This relates to the financial and logistical issues related to processing and housing the large number of migrants?a severe strain, especially in some of the smaller transit countries, which include Macedonia, Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia and Austria. The destination countries face the additional challenge regarding the integration of migrants into their societies, education systems and labour markets.

There has so far been no coordinated EU approach to dealing with the refugee situation. A voluntary quota system for the distribution of migrants between participating EU countries has shown little effect in improving the situation. A number of countries have tightened their national border controls or announced measures to do so, setting off a backwards domino effect along the main transit routes. In cases where borders to the next country on the transit route are closed, some countries fear the possible accumulation of large numbers of transit migrants within their own borders and feel forced to take tougher border control measures as well.

To address the situation, the discussions among EU countries oscillate between national interests and the determination of national, unilateral measures on the one hand, and efforts by some countries to design a comprehensive, EU-wide strategy?especially with a view towards preserving some major achievements of the EU integration process, such as the freedom of movement for people and goods?on the other. This effort of pursuing a coordinated policy approach contains several elements, including the following:

- The effective protection of the external borders of the Schengen area. Further facilities have opened in Greece for the first registration of migrants. Other EU countries and EU agencies have stepped up their assistance to Greece;

- Measures against human trafficking. NATO has started a naval mission between Turkey and Greece in an effort to limit human trafficking activity;

- Faster processing of asylum applications. This includes the faster repatriation of declined asylum application cases, helping to ensure that available resources are directed towards those truly in need;

- Mitigating the causes of the migrant flow. This includes increased assistance by the EU to the neighbouring countries of conflict zones. Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan already shelter significant numbers of refugees. The EU agreed to provide additional funding to these countries, aiming to improve the living conditions for migrants in these countries and thus reducing the pressure for them to leave for Europe.

In a number of countries, the assessment of available policy options is increasingly boiling down to a pragmatic cost-benefit analysis. This involves both the costs of integrating significant numbers of migrants into society and the looming economic losses related to trade disruption as a result of tightened border controls. An alternative scenario comprises a drastic increase in financial and non-financial assistance, especially to the first-destination countries of war refugees, with the aim of reducing the migrant flows. With the ever-rising number of migrants, the possible national benefits for EU countries that result from ramping up their international and bilateral refugee and development assistance have increased, setting the stage for more meaningful concerted actions closer to the origins of the migrant flows.

Developed economies

Poland: plans to convert foreign-exchange loans

In Poland, the President has proposed a plan to convert most of the country's outstanding foreign-exchange denominated debt into domestic currency debt, following earlier examples set by Croatia and Hungary. The proposal was not supported by the central bank, on the grounds that its implementation may impose significant losses on the commercial banks, which they estimate would cost the Polish banking system around $11 billion?the equivalent of several years of profit. The Government has already introduced a new tax on banking assets, which may further undermine banking sector profitability.

Economies in transition

Commonwealth of Independent States:

negative regional spillovers

The short-term economic indicators for the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) energy-exporters in early 2016 remained disappointing. In the Russian Federation, the Purchasing Managers Index contracted in February, despite some expansion in retail trade and a decline in inflation. In early March, the United States of America extended the economic sanctions against the Russian Federation that were introduced in March 2014 for another year.

To mitigate the social consequences of the economic downturn and to provide support to a number of industries, the Government of the Russian Federation approved an anti-crisis plan worth $9.3 billion in February, although questions remain regarding its financing.

The currencies of both energy-exporters and energy-importers in the CIS remain under pressure from low oil prices, weak confidence and declining remittances. The central bank of Azerbaijan has raised its policy rate by a total of 400 basis points since the start of the year to support the currency and encourage domestic deposits. The country's debt rating was downgraded in February by both Moody's and Fitch credit rating agencies. In Tajikistan, the central bank increased its policy rate by 100 basis points in February, and the Government has engaged in talks with the International Monetary Fund on an emergency loan, while in Kyrgyzstan the Government decided to ban dollar-denominated loans. By contrast, monetary policy was relaxed by 50 basis points in Armenia and Moldova, in line with the stabilizing inflation (although in the latter, annual inflation may still exceed 10 per cent in 2016).

In South-Eastern Europe, the National Bank of Serbia, despite a depreciation of the currency against the euro, cut its policy rate by 25 per cent in February as below-target inflation has pushed up real interest rates and the cost of capital. The National Bank of Serbia also decided to narrow the interest-rate corridor around the key rate to help to stabilize the interbank market. Europe's refugee crisis meanwhile remains a serious problem for the region, impeding trade flows.

Developing economies

Africa: drought conditions raise inflation and fiscal pressures in Southern African countries

Since early 2015, drought conditions largely attributed to El Ni?o effects have prevailed in many African countries. The situation is especially dire in Southern Africa. In 2015, large parts of Botswana, Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe experienced the lowest rainfall in decades. It is predicted that the combination of below-average rainfall and warmer-than-normal temperatures will persist until mid-2016.

Recently released gross domestic product (GDP) data for South Africa shows that real value added by the agricultural sector declined by 8.4 per cent in 2015 and reduced the GDP growth rate by 0.2 percentage points. In many other countries in the region, the agricultural sector accounts for a much higher share of GDP. This suggests that the economic damages wrought by the drought in 2015 are likely to be even worse than those observed in South Africa.

Drought conditions have had severe adverse effects on agricultural production in the region. In South Africa, corn production declined by more than 30 per cent in 2015 and is expected to decline further in 2016. As a consequence, corn prices in South Africa have surged to record levels. The price for white corn, which is the main staple, increased by 150 per cent in early 2016. Reduced grain production and the spike in food prices also prevail in many other countries in the region, including Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

South Africa is the major exporter of grain to neighbouring countries. The shortage in production is likely to require an increase in grain imports from outside the region, just when many currencies in the region have depreciated significantly vis-?-vis the United States dollar over the past few quarters. Difficulties in food supply also impact fiscal positions of Governments in the region, as they need to provide relief when revenue tends to be lower than expected.

In addition to agricultural production, the drought has also put pressure on energy supply in the region by reducing the capacity of hydropower generation. For example, the capacity for Lake Kariba, the largest man-made reservoir by volume located between Zambia and Zimbabwe, has dropped to 12 per cent in early 2016 from 53 per cent one year ago. Zambia has recently asked South Africa to supply significant amounts of electricity to meet the energy demand from mining firms. If the drought situation does not reverse soon, the power plant in Lake Kariba may be forced to cease operations, exacerbating the energy shortages.

East Asia: Indonesia and China loosen monetary stance

Bank Indonesia cut its benchmark policy rate by 25 basis points in both January and February, bringing it down to 7 per cent. The central bank had previously held a relatively tight monetary policy stance since 2013, given high inflation and fuel-subsidy reforms. However, a combination of recent developments prompts the central bank to shift away from its previous stance. The rate cuts came as Indonesia's annual output growth dropped to 5 per cent in 2015?the lowest level since 2009. Inflationary pressure has also receded in recent months as consumer price inflation averaged 4.2 per cent in the past 4 months, considerably lower than the average of 6.9 per cent recorded in the first 3 quarters of 2015. The Indonesian rupiah has been on a consistent upward trend since the beginning of 2016 despite the rate hike in the United States. It is expected that the current easing cycle will continue, as inflation is expected to remain at relatively low levels and there is a need to improve liquidity conditions of the economy.

The People's Bank of China cut its reserve requirement ratio (RRR) by 50 basis points on 1 March, bringing the ratios for big banks to 17 per cent. The cut is estimated to inject around $100 billion into the banking system and serves to maintain liquidity in the Chinese economy, as sizeable capital outflows observed in the past months has had a negative impact on money supply. Further RRR cuts are conditional on the assessment of future liquidity conditions.

South Asia: India unveils a prudent public budget

for 2016/17

The Ministry of Finance of India revealed a pragmatic and cautious public budget for FY2016. The Indian economy continues to gain momentum, but it is still far from its potential, and global economic conditions have become more challenging. The public budget, therefore, attempts to strike a delicate balance among growth, stability and pro-poor policy measures. In particular, the budget continues the fiscal consolidation path through both spending tweaks and tax increases. While the fiscal deficit is expected to reach 3.9 per cent of GDP in FY2015, the new budget pledges to reduce it to 3.5 and 3.0 per cent in FY2016 and FY2017, respectively. This consolidation only partially reduces domestic vulnerabilities, as the public debt-to-GDP ratio is relatively high, at about 66 per cent of GDP, but at the same time it allows space for further monetary easing by the Reserve Bank of India in the near term. Despite this consolidation, the public budget also attempts to provide support to growth and encompasses a number of policies targeting disadvantaged population groups. For instance, the budget displays a strong focus on the rural economy?which has been seriously affected from a two-year drought?including irrigation projects, roads, crops insurance programmes and schemes to boost job creation. In addition, the budget entails a rise in infrastructure investments and a capital injection of $3.6 billion to recapitalize public sector banks. Looking ahead, public investment in India needs to be more targeted and adequately implemented in order to crowd in private investment, which remains largely subdued due to debt distress.

Western Asia: inflation continues to exert pressure

on the monetary policy stance in Turkey

Consumer price inflation in Turkey decreased from 9.6 per cent in January to 8.8 per cent in February, as recent increases in food prices moderated. Nonetheless, inflation remains elevated and continues to exert pressure on the monetary policy stance. Against this backdrop, the central bank has been reluctant to tighten its monetary policy stance, having kept its one-week repurchase (repo) lending rate unchanged at 7.5 per cent for the past 12 months.

Latin America and the Caribbean:

near-term economic prospects deteriorate further

Amid further declines in commodity prices, significant capital outflows and volatile financial market conditions, the economies of Latin America and the Caribbean continue to face a very challenging macroeconomic environment.

Recently released data underscore the depth of Brazil's economic crisis. In the fourth quarter of 2015, GDP was 5.9 per cent lower than a year ago. Gross fixed capital formation dropped by a staggering 18.5 per cent as companies aggressively slashed capital spending amid expectations of a further contraction of demand and rising borrowing costs. Full-year GDP fell by 3.8 per cent, and by 4.6 per cent in per capita terms, the biggest annual decline since 1990. With unemployment rising?in January the rate stood at 7.6 per cent, up from 5.3 per cent a year ago?and average real wages falling, the recession is expected to persist through 2016.

The near-term growth prospects in many other countries in the region have also further deteriorated over the past few months. At the same time, inflation has been on the rise and is often well above the central banks' target levels. The increase in inflation is partly the result of the recent strong depreciations of national currencies. In some countries, for example Colombia and Peru, inflation has also been driven up by the El Ni?o weather phenomenon, which has resulted in droughts and a spike in food prices. The combination of slowing growth, strong depreciation pressures and rising inflation continues to pose a dilemma for monetary policymakers in many countries. In February, the central banks of Colombia, Mexico and Peru hiked their policy rates, aiming to bring inflation gradually back to the target range and to support their currencies. In Mexico, the surprise hike has been accompanied by direct foreign-exchange interventions to sell dollars as the authorities try to prevent high-frequency speculation. These moves have?at least temporarily?stopped the downward pressure on the Mexican peso. Since mid-February, the peso has appreciated by about 7 per cent against the dollar.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations