- Gender gaps remain pervasive worldwide, constraining economic potential

- Most countries are not on track to achieve the SDG target 8.5 ?equal pay for work of equal value? by 2030

- Eliminating gender inequalities requires legal reforms, financial incentives and shifts in societal attitudes

English: PDF (168 kb)

Global issue: Economic inequalities along gender lines remain pervasive

Despite considerable progress over the last decades, significant gender gaps persist with respect to access to labour markets, working conditions, wages, economic security, access to finance and many other areas. Across the globe, gender stereotypes and biases remain deeply entrenched. Unequal economic opportunities diminish women?s role in society and violate their basic rights, creating a vicious circle of underinvestment in human capital and sustained gender inequalities. They also curb development prospects, as demonstrated by countless empirical studies.

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), women?s global labour force participation rate stood at a mere 47 per cent in 2019, compared to 74 per cent for men. Meanwhile, women are more than twice as likely not to be in employment, education or training (NEET), at a global rate of 31 per cent against only 14 per cent for men. Women in North Africa face the largest gender gaps across all dimensions of the labour market, with only one in six women of working age in formal employment, compared with almost four in six men. The formal employment rate is also particularly low for women in Western Asia and South Asia. Labour underutilization (being out of formal employment or not being employed to their full capacity) remains very pronounced in regions where women have lower educational attainment and face restrictions in terms of geographical mobility. In many developing countries, early marriages and the need to care for children cause girls to drop out of school at a young age. Worldwide, around 10 per cent of girls aged 15 to 24 are illiterate.

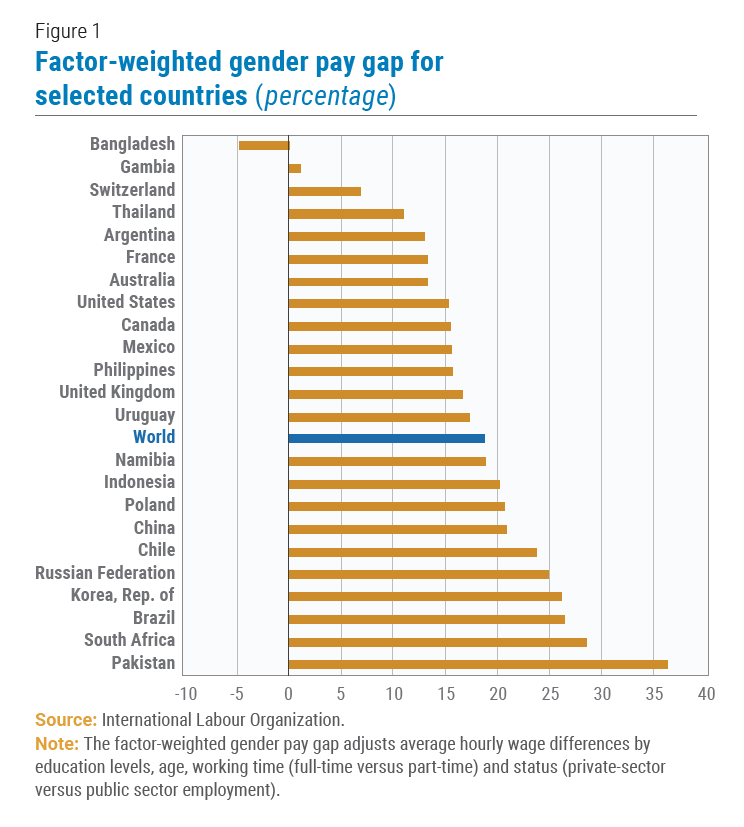

There are also persistent gender gaps with respect to job quality and wages, which are only partially explained by differences in the levels of education and skill and pay differences across industries. The global mean hourly gender wage gap stands at around 16 per cent and there are large variations across countries as shown in figure 1.

There are also persistent gender gaps with respect to job quality and wages, which are only partially explained by differences in the levels of education and skill and pay differences across industries. The global mean hourly gender wage gap stands at around 16 per cent and there are large variations across countries as shown in figure 1.

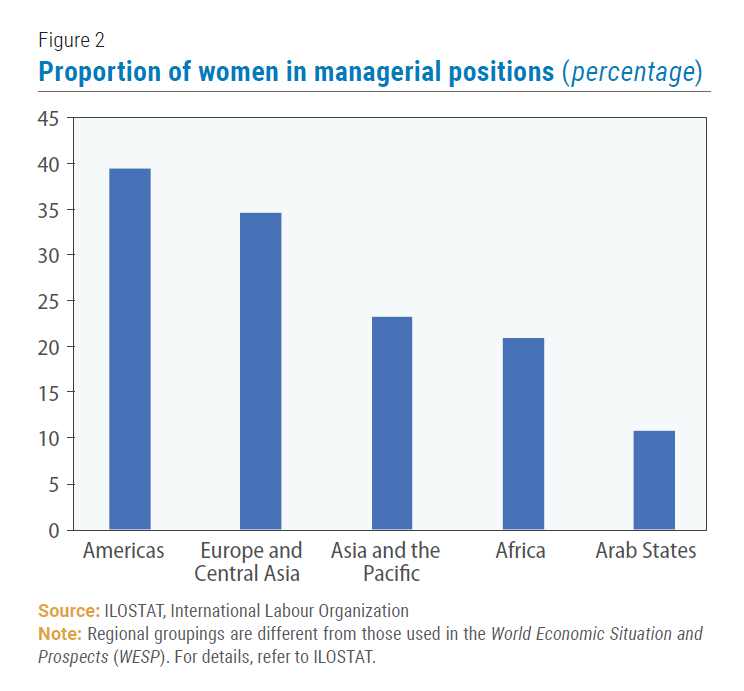

These gaps are pronounced even where women outpace men in education. For example, in Latin America and the Caribbean, average wages for women are significantly lower than for men despite women?s better education levels. This is partly a result of women?s larger participation in the informal economy, which is not covered by minimum wage standards. Worldwide, women account for about 60 per cent of contributing family workers, who are generally not receiving monetary compensation. The gender wage gap is also present in higher-skilled professions at the top of the income distribution. In most regions, the proportion of women in managerial positions is low (figure 2). Only about 18 per cent of firms are led by women?and this share is even lower in many developing countries. This is indicative of the ?glass ceiling? effect faced by women in obtaining high-level positions and negotiating higher salaries. The underrepresentation of women in high-skills sectors, including frontier technologies, is exacerbating the average wage divergence. Most importantly, the bulk of the gender pay gap across the world remains unexplained, pointing to the influence of deep-rooted stereotypes and biases.

Besides facing limited access to labour markets and lower pay, women in many countries are significantly disadvantaged in accessing credit, purchasing (or leasing) land and are often prohibited to own financial products, which restricts business and income opportunities. Gender-related income gaps are larger than wage gaps. According to a recent Centre for Global Development study based on data from 99 countries, there is an 8.3 percentage points gap in the financial inclusion between men and women, about two thirds of which can be attributed to differences in education, income and other observable factors. Across the globe, women tend to receive a lower share of corporate profits or income from financial assets. According to the World Economic Forum (op. cit), over 40 per cent of the wage gap and over 50 per cent of the income gap (the ratio of the total wage and non-wage income of women to that of men) are still to be bridged.

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8 urges countries to ?promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all?, with SDG target 8.5 setting out to achieve ?equal pay for work of equal value? by 2030. Decisive policy action is needed to address gender inequalities, including ensuring girls? access to education and policies to promote the representation of women in senior positions, in particular in science and technology. Programmes supporting women?s reintegration into the labour market after maternity leave could help mitigate the pay gap. Reducing the share of the informal economy would create a more predictable environment for women, with minimum wages and social protection regulations. Stronger labour unions may strengthen women?s negotiating power in sectors that are poorly regulated. Breaking the persistent barriers that hold back women?s full economic participation will be necessary for developing and developed economies alike to achieve their full potential.

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8 urges countries to ?promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all?, with SDG target 8.5 setting out to achieve ?equal pay for work of equal value? by 2030. Decisive policy action is needed to address gender inequalities, including ensuring girls? access to education and policies to promote the representation of women in senior positions, in particular in science and technology. Programmes supporting women?s reintegration into the labour market after maternity leave could help mitigate the pay gap. Reducing the share of the informal economy would create a more predictable environment for women, with minimum wages and social protection regulations. Stronger labour unions may strengthen women?s negotiating power in sectors that are poorly regulated. Breaking the persistent barriers that hold back women?s full economic participation will be necessary for developing and developed economies alike to achieve their full potential.

Developed economies

North America: A marked decline in labour force participation rates

In the United States, labour force participation rates for men and women had been converging for decades, with men?s labour force participation declining and women?s increasing. In the 2000s, both rates held steady, standing at 73 per cent for men and 59.5 per cent for women in 2008. Since then, the rate for both men and women have started to fall, reaching 69 per cent for men and 57 per cent for women in 2018. There are numerous explanations for this decline, including the fallout from the economic crisis in 2008?09, and the effect of demographic trends, namely the aging and retirement of the Baby Boom generation. One way to look past such demographic trends is to analyse the trends for different age groups. For the age group of 25 to 54 years, the participation rate declined for both men and women in the wake of the recession, but then ticked up again from 2015 onwards, standing at 88.6 per cent for men and 75.2 per cent for women in 2018. Both values are still below their respective levels before the economic crisis in 2008.

Developed Asia: Japan?s female labour force participation rate is at a historical high, but challenges remain

According to the latest labour force survey, the labour force participation rate in Japan has reached a historical high of 77.7 per cent, driven largely by growing female participation, which jumped from 59.8 per cent in 2009 to 70.9 per cent in 2019. Most of the increase in the female labour force participation rate took place in the age group of 30?39 years, where a significant number of female workers traditionally leave the labour market for marriage and childbearing. The trend indicates a positive social change for broader economic participation in Japan. However, as the Global Gender Gap Report 2020 (ibid.) pointed out, a significant gender gap exists in Japan in the political endowment and the representation in corporate management.

Europe: A shrinking gender employment rate gap

In all European Union (EU) Member States, the employment rate was persistently higher for men than for women between 2002 and 2018, with two exceptions: Latvia in 2010 and Lithuania in 2009 and 2010. The evolution of the employment rate of men and women over the period from 2002 to 2018, however, differed. Since 2002, the overall employment rate of women in Europe has risen, with an increase of 9.2 percentage points at the EU level. The largest increases were observed in Bulgaria, Germany and Malta. In 2018, the highest employment rate for women was found in Sweden (80.4 per cent), whereas the lowest female employment rates were recorded in Greece (49.1 per cent) and Italy (53.1 per cent). By contrast, the increase of the employment rate for men from 2002 to 2018 was more limited (3.5 percentage points). The male employment rate even decreased in 11 EU Member States, with the most visible changes observed in Cyprus and Greece. Consequently, the employment rate gap between women and men at the EU level declined notably from 17.3 percentage points in 2002 to 11.6 percentage points in 2018.

Economies in transition

Commonwealth of Independent States: Stronger efforts are needed to overcome gender gaps in Central Asia

Among the CIS countries, the Russian Federation has relatively low economic gender inequality. The labour force participation rate among Russian women, who on average have higher educational attainment than men, is relatively high?close to 70 per cent. Women are well represented in professional positions across different industries. Nevertheless, gender-related wage gaps are still present?men earn on average around 20 per cent more than women. There are also persistent income disparities, partially explained by the low level of women?s representation at senior managerial positions and limited ownership of businesses or financial assets.

By contrast, the countries in Central Asia exhibit noticeable economic inequality along gender lines, in part due to the entrenched social norms and traditions which resurged in the last decades. For example, in Tajikistan the labour force participation rate has hovered around 30 per cent for women, versus around 60 per cent for men. Even in the countries with smaller participation rate gaps, unemployment rates for women are higher, partially reflecting lower education levels. Many women, especially in rural areas, are confined to unpaid family work, in particular in low-productivity agricultural activities on small farms. Gender asymmetries are also visible in land ownership and leasing. In the non-agricultural private sector, women are also underrepresented, as some countries have extensive job restrictions on women for certain occupations. A range of policies is being implemented in the region to address the gender gaps. Some progress has been accomplished, in particular in addressing early marriages and ensuring girls? access to education, but more needs to be done.

Developing economies

Africa: ICT gender gaps could exacerbate existing socio-economic inequalities

Africa faces deep-rooted and large gender gaps on many socioeconomic dimensions, including poverty, education, employment, wages, economic security and access to finance, among others. Despite rapid expansion in recent years, a significant gender gap also exists in the access to and use of information and communication technologies (ICT) across the continent.

Africa displays one of the highest internet user gender gaps in the world, at about 33 per cent against 2.3 per cent in developed countries and 23 per cent in developing countries. Meanwhile, sub-Saharan Africa also has one of the lowest rates of mobile phone ownership and mobile internet use of women?average mobile phone ownership for women is only 69 per cent (compared to 81 per cent for men). At around 15 per cent, this is the second highest gender gap, after South Asia. The gap is much larger than in East Asia and Latin America. Given the prevalence of mobile banking in some African countries, this also affects women?s access to finance. Differences regarding the use of mobile internet are also substantial. Only 29 per cent of women use mobile internet in sub-Saharan Africa, more than 40 percentage points below the rate for men. This means that about 200 million women in sub-Saharan Africa do not use mobile internet.

These ICT gender divides in Africa significantly constrain the positive economic and social effects of technology diffusion. Furthermore, rather than ICT becoming an equalizing factor for gender across societies, there is a risk that its unequal diffusion could worsen existing socioeconomic inequalities. Thus, there is a crucial role for public policies across the continent to promote fast and gender-balanced diffusion of modern technologies.

East Asia: Gender gaps remain a key development challenge

Over the past few decades, East Asia has made steady progress in reducing gender inequalities across several dimensions. On the education front, strong gains have been made in girls? educational attainment. Girls have higher secondary school attendance and completion rates, while in most major Southeast Asian economies, more women than men attend tertiary education institutions. In terms of economic opportunities, many countries in the region have introduced regulatory frameworks that grant women equal access to work opportunities, freedom from workplace discrimination, and maternity leave.

Nevertheless, gender gaps in other dimensions remain a key development challenge. For the region as a whole, recent ILO figures show that the labour force participation rate for women (at 59.6 per cent in 2019) remains consistently lower than for men (74.9 per cent). Gender pay gaps are still high in East Asia, but with considerable variation across countries. For example, based on monthly earnings, the mean gender pay gap between men and women is 36.7 per cent in the Republic of Korea, 19 per cent in China, and 17.8 per cent in Indonesia. In contrast, the gap is -6.6 per cent in the Philippines. Furthermore, rapid urbanisation and migration in many parts of the region have the potential to fragment social support, thus increasing women?s work burden, including domestic work and childcare.

South Asia: Gender inequalities hamper South Asia?s development

Gender inequalities remain large in South Asia, holding back the region?s development prospects. Despite significant progress over the last decade, South Asia is among the most gender unequal regions in the world, as documented by the UNDP?s Human Development Report 2019 and the World Economic Forum?s Global Gender Gap Report (2018). The region?s gender gap in labour force participation is the highest in the world, with a labour force participation rate of 79 per cent for men against a meagre 26 per cent for women. Moreover, men are 50 per cent more likely than women to have completed secondary education.

The political response to many of these gender inequalities has been insufficient, even as some important steps have been taken. Bangladesh, for example, has made significant progress in terms of political empowerment of women. India, on the other hand, has made strides in reducing wage inequality and closing the tertiary education gap. Across the region, rates of child or early marriage have declined, giving young women a better chance to continue their education and develop to their full potential. However, harmful social and gender norms often prevail, coupled with a failure of protective legislation. These gender inequalities severely limit the region?s continued development prospects.

Western Asia: Growing female workforce in Saudi Arabia contributes to economic diversification

Gender gaps in Western Asia remain substantial, but countries have made important progress in recent decades, especially in the areas of education and employment. In 1999, Saudi Arabia?s labour force participation rate was 59.6 per cent for men and 10.1 per cent for women. In the third quarter of 2019, it reached 67 per cent for men and 24.5 per cent for women. Women?s labour force participation rate has been rapidly growing recently thanks to a series of reform measures, such as allowing women to obtain driving licenses. Increasing female labour force participation is also rooted in the consistent growth of educational attainment by Saudi women. The gross enrolment ratio for tertiary education for women rose from 25 per cent in 2000 to 69 per cent in 2018. Yet, Saudi Arabia still relies heavily on foreign workers, particularly in the private sector. In 2019, the share of foreign workers stood at 80 per cent. Wider economic participation of Saudi women is necessary for fostering a more dynamic private sector and accelerating economic diversification, while also supporting the long-standing domestic objective of labour force nationalization.

Latin America and the Caribbean: Despite progress on several fronts, gender pay gaps remain pervasive

Although gender gaps in Latin America and the Caribbean have narrowed over the past few decades, particularly in terms of educational achievement, significant disparities in terms of economic participation and opportunity persist. Nowadays, women across the region outperform men in educational attainment. In 2017, 29 per cent of women held a tertiary degree (at least 13 years of formal education), compared to only 19 per cent of men. Just 22 per cent of women had less than six years of education against 30 per cent of men. However, these educational achievements often do not translate into improved work opportunities. Three factors contribute to still considerable gender pay gaps in the region. First, women in Latin America and the Caribbean spend much more time than men on unpaid work and are less likely to hold paid full-time jobs. In 2017, the labour force participation rate stood at 75 per cent for men, but at only 50 per cent for women. Second, women tend to work in lower-paid occupations. The share of informal employment in total employment is higher for women than for men, especially in Central America. Moreover, women tend to be overrepresented in some low-paying service sector jobs and underrepresented in high-paying positions. In 2016, women held only 7.3 per cent of the board seats of Latin America?s 100 largest companies. Third, even within the same occupation, women are paid less than men. After accounting for age, educational level, residence area, type of work and household structure, women still earned on average 17 per cent less than men.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations