Download the World Economic Situation and Prospects Monthly Briefing No. 75

February 2015 Summary

- ??Major central bank policy swings in Switzerland and the euro area

- Euro area deflation sets in

- Oil exporters face increased fiscal challenges, while lower commodity prices ease inflationary pressures

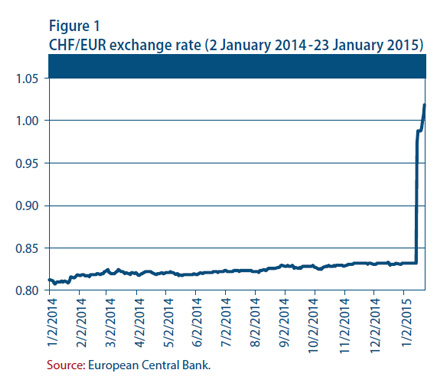

The Swiss National Bank abandons its minimum exchange rate on the euro against the franc

The Swiss National Bank (SNB) abandoned its minimum boundary on the exchange rate of the euro to the Swiss franc (CHF), which was introduced in 2011 and set at 1.20 CHF to the euro. At that time, the euro crisis caused major capital flows away from the euro into the franc. To limit the detrimental impact of further currency appreciation for the economy and, in particular, exports, the SNB announced the minimum exchange rate. Subsequently, in light of continued capital flows into the franc, maintaining the exchange rate floor required the SNB to buy euros and sell francs. This led to an increase in foreign currency reserves by 64 per cent from September 2011 until November 2014, to 463 billion CHF, which is equivalent to 73 per cent of Switzerland's gross domestic product (GDP). On 15 January, the SNB announced the removal of the minimum exchange rate, leading to an immediate appreciation of the franc against the euro by 19 per cent (figure 1). As reasons for its action, the SNB cited a less pronounced overvaluation of the franc against the euro, the depreciation of the franc together with the euro relative to the dollar, and the increasing divergence in monetary policies of the major economies. The SNB also lowered the interest rate on sight deposit account balances by 50 basis points to -0.75 per cent to avoid too strong a monetary tightening effect from the removal of the minimum exchange rate. The fallout from the appreciation still remains to be seen, but a significant recessionary impact on the Swiss economy seems possible as the stronger franc will put pressure on Switzerland's exports, which make up about 72 per cent of GDP and of which 46 per cent go to the euro area.

>

The European Central Bank unleashes a large quantitative easing programme

In January, the European Central Bank (ECB) decided to launch an expanded asset purchasing programme in the euro area, as an attempt to counter the threat of a deflationary spiral and to raise inflation to its target of just below 2 per cent. The programme, far larger than investors had expected, includes monthly purchases of public and private securities of ?60 billion until September 2016, and it encompasses the existing purchase programme for asset-backed securities and covered bonds (about ?10 billion per month). Even though this open-ended quantitative easing (QE) could include assets purchases of about ?1.1 trillion, the ECB and national central banks will not buy more than one third of a country's debt issuance, and special rules will apply to purchasing bonds issued by countries under a European Union (EU)/International Monetary Fund (IMF) adjustment programme. Most importantly, the bulk of potential losses from default or restructuring of national debts will be borne by national central banks, as only 20 per cent of the purchases will be subject to a regime of "risk sharing". In addition, the ECB cut the interest rates of its targeted longer-term refinancing operations. With these decisions, the ECB further eases its monetary policy stance and adopts a similar approach to the United States Federal Reserve and the Bank of England, which introduced large QE programmes in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

The introduction of the expanded asset purchasing programme was welcomed by global financial markets, with stock markets rising and sovereign bond yields declining across the board. Also, the euro depreciated to its lowest level in more than 11 years against the dollar, a trend that might help increasing inflation expectations. In the medium term, the QE policy also intends to ease credit crunches and thus strengthen the lending capacity of banks, which should promote economic activity and investment. Nevertheless, several factors may limit its economic effects. First, expectations over the QE by the ECB already led to a noticeable reduction in bond sovereign yields in Southern Europe, with the exception of Greece. Second, bank financing is predominant in the financial sector of the euro area, which may deny private firms the opportunity to benefit significantly from the effect of the QE on capital markets. It also remains to be seen how this aggressive monetary measure will be complemented with structural reform and fiscal policies. While the ECB emphasizes "growth-friendly" fiscal consolidation and further structural reform to raise productivity and investment others argue that fiscal policy should move to a more proactive stance to support aggregate demand.

Developed economies

North America: low oil prices with diversified consequences

In the United States of America, according to the advance estimate of GDP, the economy expanded by 2.6 per cent in the fourth quarter. This notable slowdown, compared with 5.0 per cent in the third quarter, was mainly caused by an increase in imports of goods and a decrease in government outlet, especially national defense expenditure. Meanwhile, the growth rate for private consumption accelerated further and reached the level of 4.3 per cent, the highest since the end of the Great Recession. The deflator for private consumption of goods dropped considerably over the same quarter, owing to the appreciation of the U.S. dollar and lower oil prices.

On 21 January 2015, the Bank of Canada (BoC) lowered its policy rate by 25 basis points to 0.75 per cent. According to the policy statement, BoC considered that sustained low oil prices may impose a significant negative impact on the Canadian economy. In its own study, the BoC showed that permanent decline of oil prices from $110 per barrel to $60 per barrel would reduce GDP by 1.4 per cent during the next eight quarters, assuming no monetary policy response. After this unexpected move, depreciation of the Canadian dollar vis-?-vis the U.S. dollar accelerated significantly and brought the monthly magnitude of depreciation to a record high in January 2015.

Developed Asia: the double-edge sword of Japan's higher tax

In late January 2015, the Japanese Government proposed a supplementary budget for the current fiscal year, ending in March 2015. The size of the supplement budget is 3.1 trillion yen, just about 0.6 per cent of GDP. This supplement budget will be funded by extra tax revenues and unspent funds saved from previous years. For the next fiscal year, the budget proposed by the Government includes a minor increase in outlet. Nevertheless, the debt-to-dependence ratio is predicted to decline to 38.6 per cent in 2015 from 43.0 per cent in 2014. The higher consumption tax rate, introduced in April 2014, is expected to generate 9 per cent more tax revenues in the next fiscal year compared with the current one.

Meanwhile, household consumption is still lower than prior to the tax rate hike. Nominal retail sales have declined for three months consecutively, from October to December 2014. However, growth in export volume accelerated in the same quarter, while import growth remained steady. Lower energy prices have caused the Japanese nominal trade balance to decline over the past few months. Industrial production has bottomed- out from the trough since September. The employment level has maintained its upward trend over the past two years, with the employment level in December 2014 increasing by 0.6 per cent year on year.

Western Europe: deflation sets in

Euro area annual inflation is expected to be -0.6% in January 2015, down from -0.2% in December 2014, according to the latest estimate from Eurostat (the statistical office of the EU). This negative rate for euro area annual inflation in January is mainly driven by the fall in energy prices (-8.9, compared with -6.3% in December). The January slide of the inflation rate matches the biggest decline in prices in the history of the single currency, according to data published by Eurostat. In the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, December inflation was also particularly low, 0.5 per cent, which may encourage a prolonged period of expansionary monetary policy.

In the euro area, as declining prices are combined with high unemployment, the ECB announced a ?1.1 trillion stimulus plan centered on government bond purchases (see global section). It is still unclear whether this plan will provide enough incentive to return inflation to the ECB goal of just under 2 per cent. Even though unemployment fell to the lowest level since August 2012 in the euro area, there are still major discrepancies among countries, according to recent Eurostat data. The unemployment rate stood at 4.8 percent in Germany, while it stood at 23.7 percent in Spain and 25.8 per cent in Greece. In Greece, after enduring five years of austerity measures and experiencing high joblessness, voters elected a new government, which pledged to renegotiate the bailout programme.

Consequently, nervousness increased in European financial markets, fueled by uncertainty about a Greek debt default and ultimately about the stability of its banking system, which still relies on ECB loans to fund day-to-day operations.

The new EU members: positive trends continue, but stronger Swiss franc affects households

Positive economic trends continued in most of the new EU members in the final quarter of 2014. In the largest regional economy, Poland, industrial output in December grew by 8.4 per cent year on year, real wages increased and PMI indicators were favourable. According to a flash estimate, the Polish economy expanded by 3.3 per cent in 2014; growth was driven by domestic demand and became less dependent on external factors. In Slovakia, however, industry weakened in the last quarter, as car sales to the Russian Federation declined.

Lower fuel costs, along with the diversion of food supply to local markets following the Russian food import ban, sustained deflationary pressures in the region. In Hungary, consumer prices in December dropped by a record 0.9 per cent year on year. In January and February, the Romanian National Bank cut its policy rate. However, the recent appreciation of the Swiss franc (in which many long-term household loans in Central Europe are denominated) has led to concerns about the macroeconomic impact on the new EU members due to the fact that some of the region's currencies weakened, limiting room for further monetary loosening. Consequently, the share of non-performing loans could rise in Croatia, Poland and Romania. In January, the Government of Croatia suggested fixing the exchange rate of the kuna versus the Swiss franc for mortgage holders. The proposal was approved by the Parliament but not fully supported by the banking sector. In January, Lithuania joined the euro area, with a smooth transition to the common currency.

Economies in transition

CIS: lower oil prices challenge the near-term macroeconomic outlook

The precipitous fall in oil prices in the last months of 2014 had a profound impact on the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) economies, aggravating economic prospects for 2015. In November, the GDP of the Russian Federation contracted year on year for the first time in five years. Following a currency crisis in December, the Central Bank sharply increased its key policy rate by 650 basis points to 17 per cent, to stabilize the rouble. This initiative considerably increased the cost of capital and was partially reversed in January, with a rate cut of 200 basis points. Capital outflows in 2014 are estimated at $151 billion (according to the central bank's methodology). The Government of the Russian Federation has approved a bank recapitalization scheme worth about $15 billion and an anti-crisis plan, which preserves social spending.

Other energy exporters from the CIS may also face problems created by the fall in oil prices. As a result, the Government of Kazakhstan has decided to revise the budget for 2015-2017. In Ukraine, the ongoing military conflict in the industrial eastern part of the country has led to a 10 per cent collapse in industrial output in 2014, while inflation approached 25 per cent in December, following a weaker currency and higher energy tariffs. The country is seeking a new, longer-term arrangement with the IMF, as it may face a balance-of-payments crisis.

For small energy importers in the CIS, the dwindling inflow of remittances from the Russian Federation and the partial loss of the Russian market will outweigh the benefits derived from lower fuel costs. The currencies of most CIS economies depreciated in parallel with the Russian currency, which spurred inflation. In January, the Central Bank of Armenia increased interest rates, while Turkmenistan devalued its currency by 19 per cent versus the dollar. On 1 January 2015, the Eurasian Economic Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan and the Russian Federation came into force. Armenia joined the Union on 2 January, and Kyrgyzstan is planning to join in May.

South-Eastern Europe: annual GDP declines in Serbia

In Serbia, GDP is estimated to have declined by 2 per cent in 2014, as a consequence of the devastating floods in May. Inflation remained low in December, at 1.7 per cent, as consumer prices fell by 0.4 per cent month on month. The National Bank of Serbia had to intervene in the currency market in January to bolster the value of the currency, which weakened over concerns about Swiss franc denominated loans. The Government and the National Bank of Serbia are considering different options to provide debt relief to holders of such loans.

Developing economies

Africa: falling oil prices weigh on oil producers, while reducing inflation in other countries

Falling energy prices have begun to weigh on some oil exporters such as Algeria, which saw its export surplus fall from 5.6 per cent of GDP in 2013 to 2.5 per cent of GDP in 2014. This is expected to weigh heavily on the Government's budget, which relies on oil revenues for up to 60 per cent of total revenue. This is particularly problematic as the expected deficit was already projected to be large, at 22 per cent of GDP for 2015?an estimate made when oil prices were still projected to be $90 per barrel, which is over 40 per cent higher than current prices. This has led officials to raise the issue of cutting subsidies, which cover a wide variety of goods and services and represent 30 per cent of GDP. This could lead to social unrest as unemployment was already rising, up from 9.8 per cent in April 2014 to 10.6 per cent in September.

On the other hand, other countries have benefitted from falling energy and food prices as inflation has declined across a number of countries in Africa. In Ghana, GDP growth for 2014 was revised downward to 4.2 per cent from 6.9 per cent because of data methodology issues. GDP expanded by 2.5 per cent in 2014 in Morocco, down from 4.4 per cent in 2013, partly owing to bad weather, which reduced agricultural output by over 30 per cent.

East Asia: China's growth slowed moderately in 2014, in line with Government target

China's economy grew by 7.3 per cent year on year in the fourth quarter of 2014, the same pace as in the previous three months. Economic activity was supported by various policy measures, including a cut in interest rates and acceleration in investment approvals. Full-year growth slowed from 7.7 per cent in 2013 to 7.4 per cent in 2014. While this was the weakest annual expansion since 1990, it was in line with the Government's target of about 7.5 per cent growth. The full-year figures also indicate some progress in rebalancing the economy towards the service sector on the supply side and towards consumption on the demand side. At the same time, the income gap between rural and urban households narrowed further, but still remains significant. In the Republic of Korea, economic growth slowed markedly in the fourth quarter of 2014 amid a sharp drop in construction investment and ongoing weakness in the external sector. Seasonally adjusted GDP grew by only 0.4 per cent from the previous quarter, the slowest pace in two years. Full-year growth in 2014 was 3.3 per cent, slightly up from 3.0 per cent in 2013. In response to subdued growth and persistent disinflation, the Monetary Authority of Singapore eased monetary policy in January by seeking a slower rate of appreciation against a basket of currencies.

South Asia: central banks of India and Pakistan cut interest rates amid falling inflation

Amid a marked decline in inflation, the central banks of India and Pakistan lowered their main policy interest rates in January. With oil prices plummeting and other global commodity prices also declining, inflation rates across South Asia have fallen to their lowest levels in several years. In parts of the region, including India and Pakistan, a sharper than expected fall in the prices of fruits and vegetables and weak demand conditions have also contributed to lower inflationary pressures. In India, wholesale inflation declined to only 0.1 per cent year on year in December, while consumer price inflation slowed to about 5.0 per cent. In mid-January, the Reserve Bank of India cut its main policy rate for the first time in two years, lowering the repurchase rate by 25 basis points to 7.75 per cent. The authorities also hinted at further easing, should the disinflation process continue. In Pakistan, consumer price inflation has slowed to a multi-year low of about 4.0 per cent, prompting the central bank to lower its main policy rate by 100 points to 8.5 per cent.

Western Asia: fiscal deficits expected in several Gulf economies

Many Western Asian economies face fiscal budget deficits in the light of current oil prices. As oil prices remain at about $55 per barrel, fiscal revenues are expected to drop significantly in 2015. However, government spending in non-oil sectors remains the main plan to compensate for slower oil output. Oman's 2015 state budget released earlier this month includes an increase of government spending by 4.5 per cent from the 2014 spending plans. As a result, this overall spending is expected to increase the fiscal deficit from an estimated 0.8 per cent of GDP in 2014 to about 8.0 per cent in 2015. Similarly, in Saudi Arabia, current spending levels would lead to a fiscal deficit of 6 per cent of GDP for 2015 if oil prices remain unchanged. So far, Governments have played down the need for change, seating on healthy financial reserves or relying on short-term borrowing, which would allow spending through a period of low oil prices. However, if prices do not rebound by the middle of the year, Governments may need to revise their fiscal strategies. At the same time, inflation is falling in several countries. In Oman, inflation reached a 5 month low of 0.8 per cent in December, mainly due to lower food prices. On January 20, the Central Bank of Turkey cut its main policy rate by 50 basis points, to 7.75 per cent. This decision reflects not only lower inflation pressures and lower five-year government bond yields, but also the need to stimulate private investment. As a result, prospects for the Turkish economy have improved, owing both to lower oil costs and interest rates cuts.

Latin America and the Caribbean: the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela facing a new round of economic challenges

The Venezuelan economy is under an extremely challenging situation, characterized by recession, high inflation, declining reserves and rising public deficit. Furthermore, the recent collapse in oil prices adds another critical pressure on the economy, as oil represents more than 90 per cent of total exports and about 50 per cent of public revenues. As a result, government revenues are plummeting and the fiscal balance is under threat, while imports continue to fall, exacerbating shortages of several products. In January, the Government unleashed an economic plan in an attempt to contain and manage the situation. Among other measures, the plan includes an increase of minimum wages and pensions by 15 per cent, a probable increment in domestic gas prices, and modifications of the currency-exchange system. The sharp decline in oil prices is also affecting other Latin American countries. In Mexico, fiscal balance is at risk, as one third of public revenues comes from the oil sector. Despite their stable macroeconomic management, Bolivia and Colombia will experience a reduction in foreign-exchange earnings, increasing pressures on the domestic currency and fiscal balances. In Argentina and Brazil, effects on the balance of payments and fiscal balances will be minimal. However, investment prospects in the oil sector can be seriously affected, especially if oil prices continue to be low. Conversely, in Chile, lower oil prices are boosting economic activity, as the economy is heavily dependent on oil imports.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations