The collapse of global trade and implications for developing regions

Global trade in goods and services tumbled in 2020

Global trade in goods and services tumbled in 2020

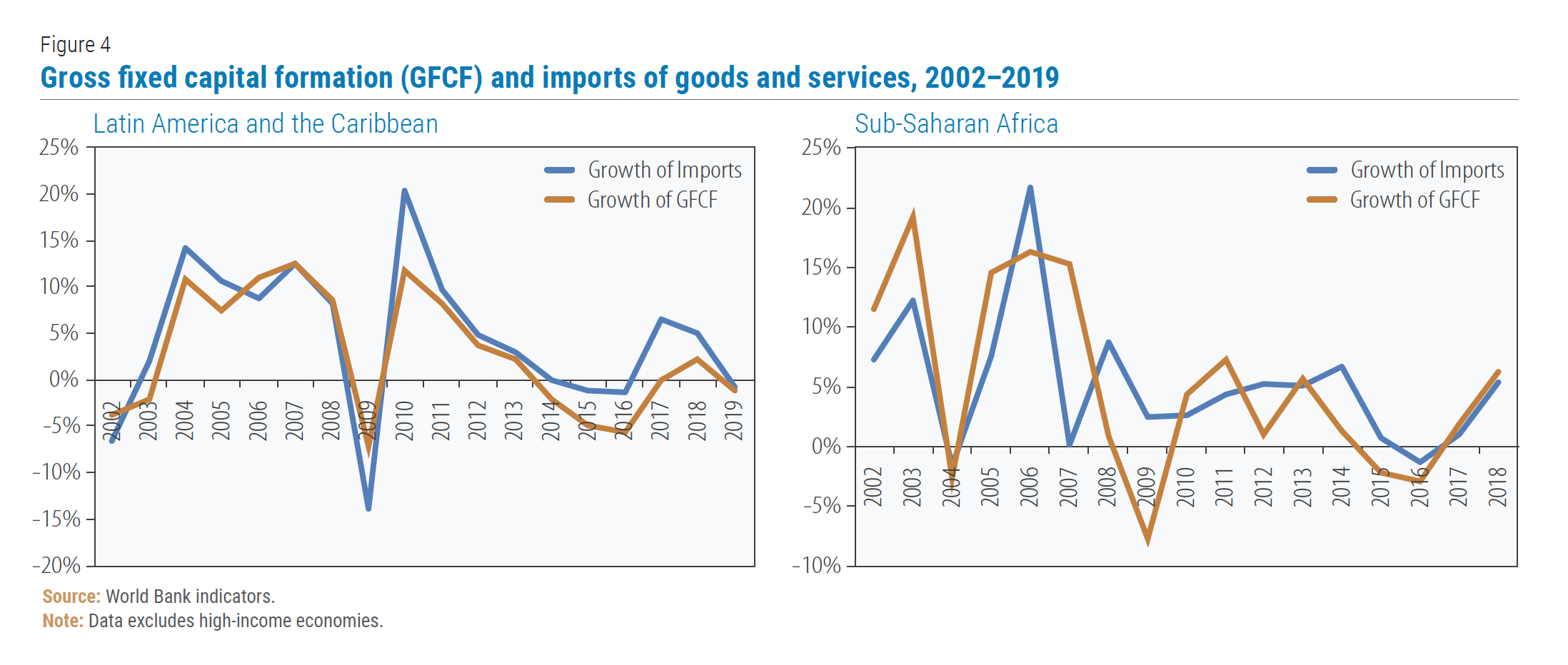

International trade sputtered to a halt in the first half of 2020, as the novel coronavirus pandemic prompted widespread lockdowns, curtailed factory output, disrupted transportation and depressed demand. Global merchandise trade shrank by 3 per cent year-on-year in the first quarter of 2020, according to the World Trade Organization (WTO) (figure 1). Compared with the preceding quarter, trade volume shrank by 2 per cent in seasonally adjusted terms. Global services exports fell harder, by 7.6 per cent year-on-year in the same period and contracted by 7.3 per cent compared with the previous quarter in seasonally adjusted terms.

Initial estimates for the second quarter of 2020 by the WTO point to a year-on-year plunge in global merchandise trade of approximately 18.5 per cent as the virus and associated lockdown measures affected a greater share of the world. Given the intensification and subsequent relaxation of social distancing measures and restrictions on travel and transport in most countries during the second quarter of 2020, it is possible that trade may have recovered somewhat since then. Some indication of this can be seen in the increase in global commercial flights (including international air cargo) and container port throughput. Purchasing managers indices have also started to recover.

In the second half of the year, international trade is likely to remain below the levels of last year. UNCTAD expects that the decline in international trade will be approximately 20 per cent for the year 2020. The WTO expects a decline between 13 and 32 per cent. Currently, trade would only need to grow by 2.5 per cent per quarter for the remainder of the year to meet the optimistic end of the WTO?s projection. Nevertheless, downside risks could materialize in the form of adverse developments, including a second wave of COVID-19 outbreaks, weaker-than-expected demand growth or widespread expansion of trade restrictions. For the year 2021, WTO projections point to merchandise trade volume growth of between 5 per cent and 20 per cent, depending on the pace of economic recovery, in turn shaped by monetary, fiscal and trade policy choices.

Trade fell sharply in developing countries though with some heterogeneity

Trade fell sharply in developing countries though with some heterogeneity

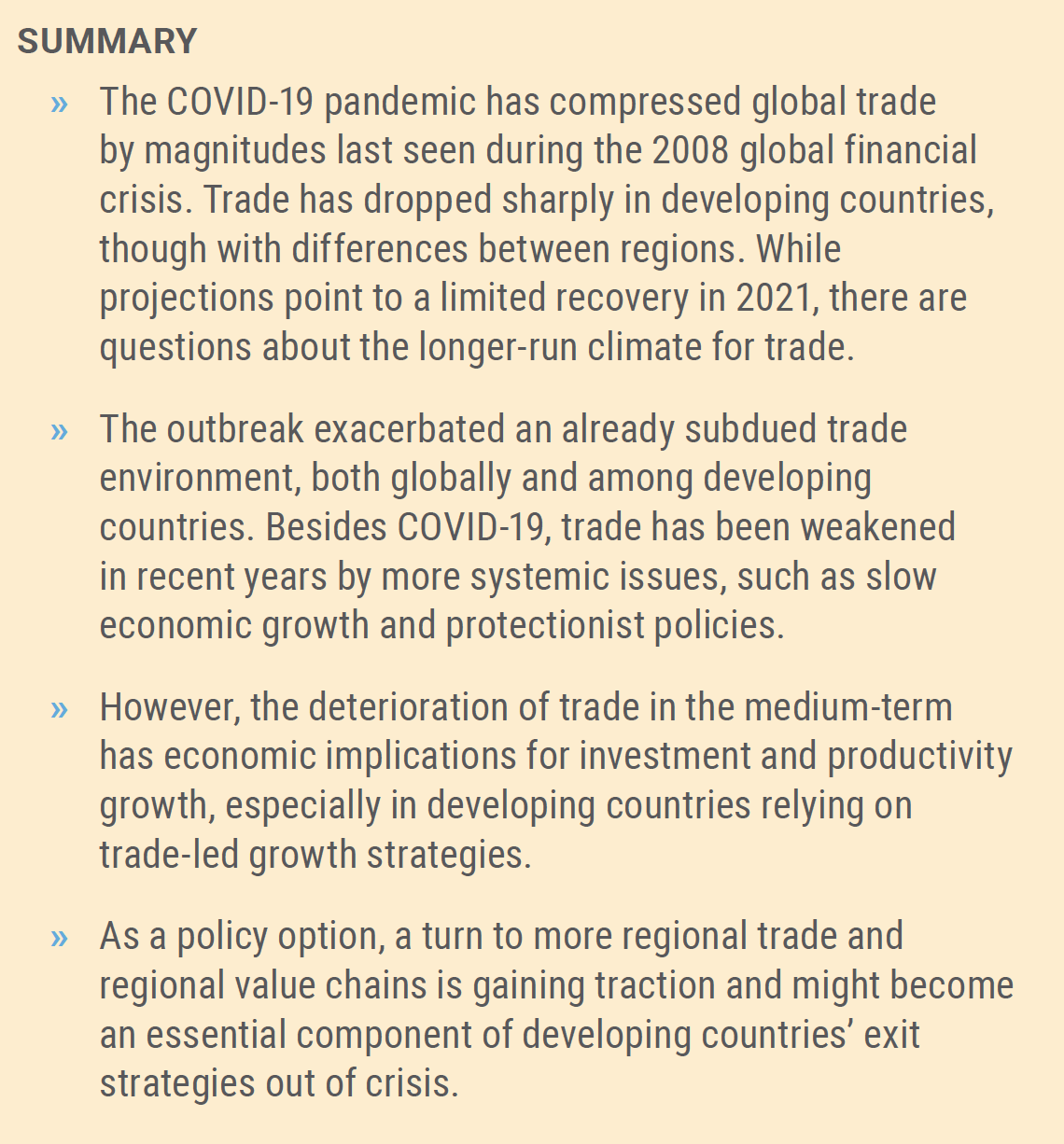

Developing countries? exports in the first quarter fell 7 per cent, while imports fell 2 per cent and South-South trade (i.e., trade between developing countries) decreased 2 per cent. The decline in trade in Q1 2020 was followed by a deeper decline in April: exports contracted 18 per cent and imports dropped 19 per cent, while South-South trade fell 14 per cent.

All regions in the world observed declines in international trade in Q1 2020 and April 2020 (figure 2). However, trade in developing countries appears to have fallen faster in April relative to developed countries. Also, the decline in the East Asia and the Pacific area remained in the single digits, unlike in other regions. A deep downturn in Q2 is expected among developing countries, as data for April showed declines of up to 40 per cent for countries in South Asia and the Middle East, for instance. The impact of the pandemic on trade in services was especially acute due to international and national travel restrictions.

Nearly 90 per cent of the world economy came under some form of lockdown measures by mid-April. Reflecting this, services exports fell 16.1 per cent in Asia and Oceania and 10.4 per cent in Latin America and the Caribbean in Q1 compared with a year ago?well above the world average of 7.6 per cent. As expected, travel services exports fell the hardest, with drops of 35 per cent in Asia and 17.7 per cent in Latin America compared with the same quarter last year. International tourist arrivals are experiencing the worst crisis since records began in 1950. Tourist arrivals in Asia fell 60 per cent in the first five months of 2020 over the same period of last year. In the same period, the Middle East received 52 per cent less tourists and Africa experienced 47 per cent less visits. Imports of services fell as well in Q1, by 18.8 per cent in Asia and 9.6 per cent in Latin America year on year.

Looking ahead, trade growth in developing countries is expected to see a limited recovery. In 2020, Latin American merchandise trade volume is projected to decline about 18 per cent to 38 per cent, and Asian trade could decline 13 per cent to 34 per cent, according to the WTO. In 2021, April projections point to 17 per cent to 21 per cent growth in Latin America, and 24 per cent to 31 per cent growth in Asia. However, given base effects, these estimates still project a cumulative fall by 2021.

Trade weakness is in part caused by current demand-side weakness

The decline in developing countries' export revenues is driven by lower demand in destination markets and lower international commodity prices. One fourth of exports of commodities from commodity-dependent developing countries, which constitute two thirds of developing countries, go to China. Globally, one fifth of world commodities exports are shipped to China. The drop in Chinese demand is expected to affect developing countries? producers of energy products (e.g., natural gas) and ores (e.g., iron ores). As demand for commodities tumbles, so do commodity prices, which, despite a mild recovery in June, still stood 20 per cent below last year?s level . This is mainly attributed to lower fuel prices and, to a lesser degree, agricultural raw materials prices. Overall, in 2020, global exports of commodities to China are estimated to decrease significantly as compared to a situation without the COVID-19 crisis. For commodity-dependent developing countries, exports of commodities to China are estimated to drop between $883 million and $5.7 billion with respect to benchmark figures.

On the other hand, reduced imports in developing countries may indicate weaker demand as well as exchange rate movements. Developing countries? currencies, some of which were facing currency stress prior to 2020, have seen the worst impact by the pandemic. Since the year commenced, the currencies of Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) and Zimbabwe experienced over 70 per cent depreciation against the US dollar. Other affected currencies are those of Brazil, Seychelles and Zambia, experiencing over 20 per cent depreciation against the US dollar. Concerns regarding debt have also possibly reined in imports as borrowing costs peaked in Q1 2020. April projections by the IMF point to an increase in low-income developing country gross debt of 4.5 percentage points (47.4 per cent of GDP) in 2020?the highest increase since 2015? which is only partially explained by the predicted decline in GDP. Shortage of foreign currency is yet another factor constraining imports in countries such as Egypt and Nigeria.

Systemic supply-side issues were at the heart of slow trade preceding the pandemic

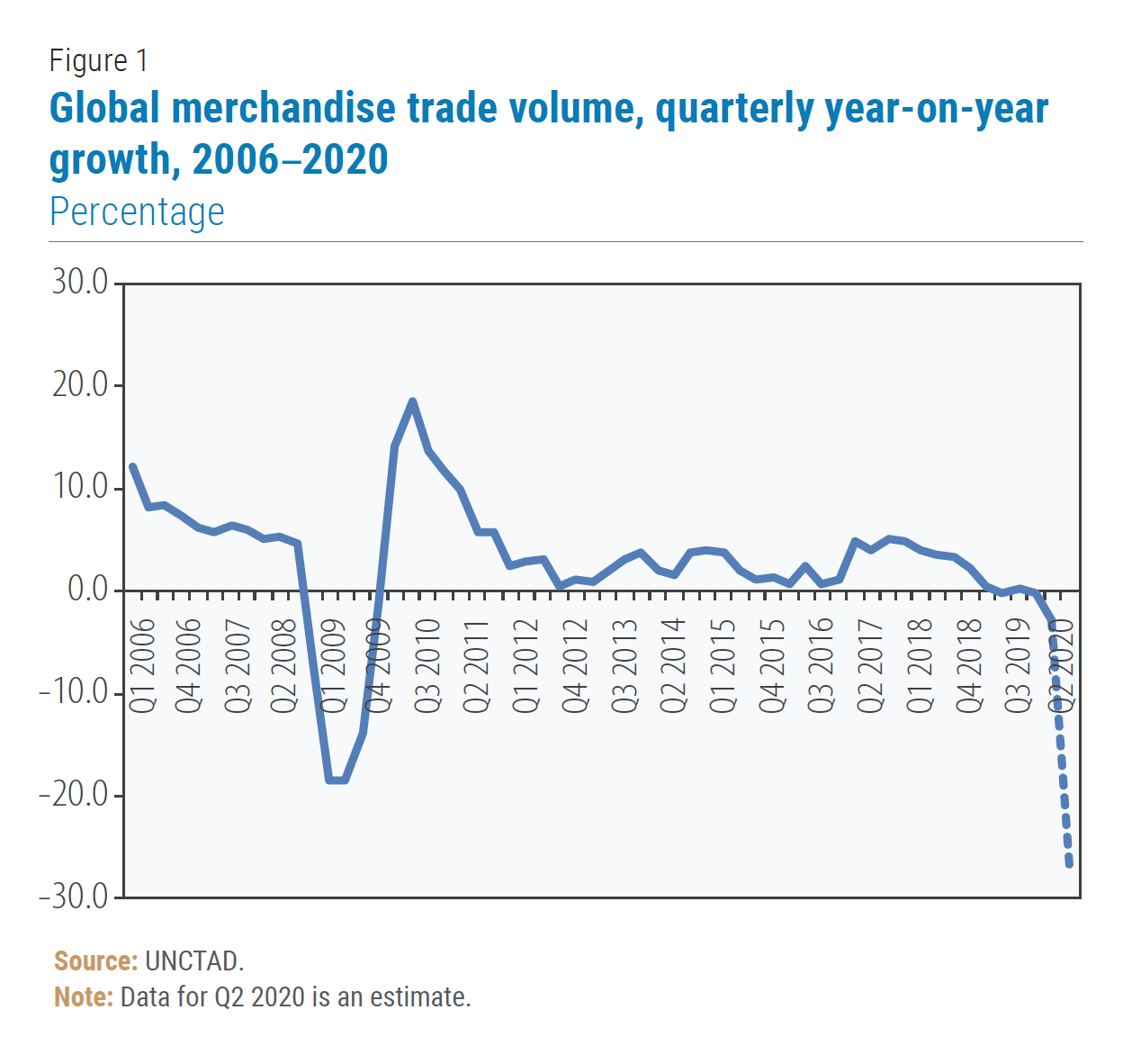

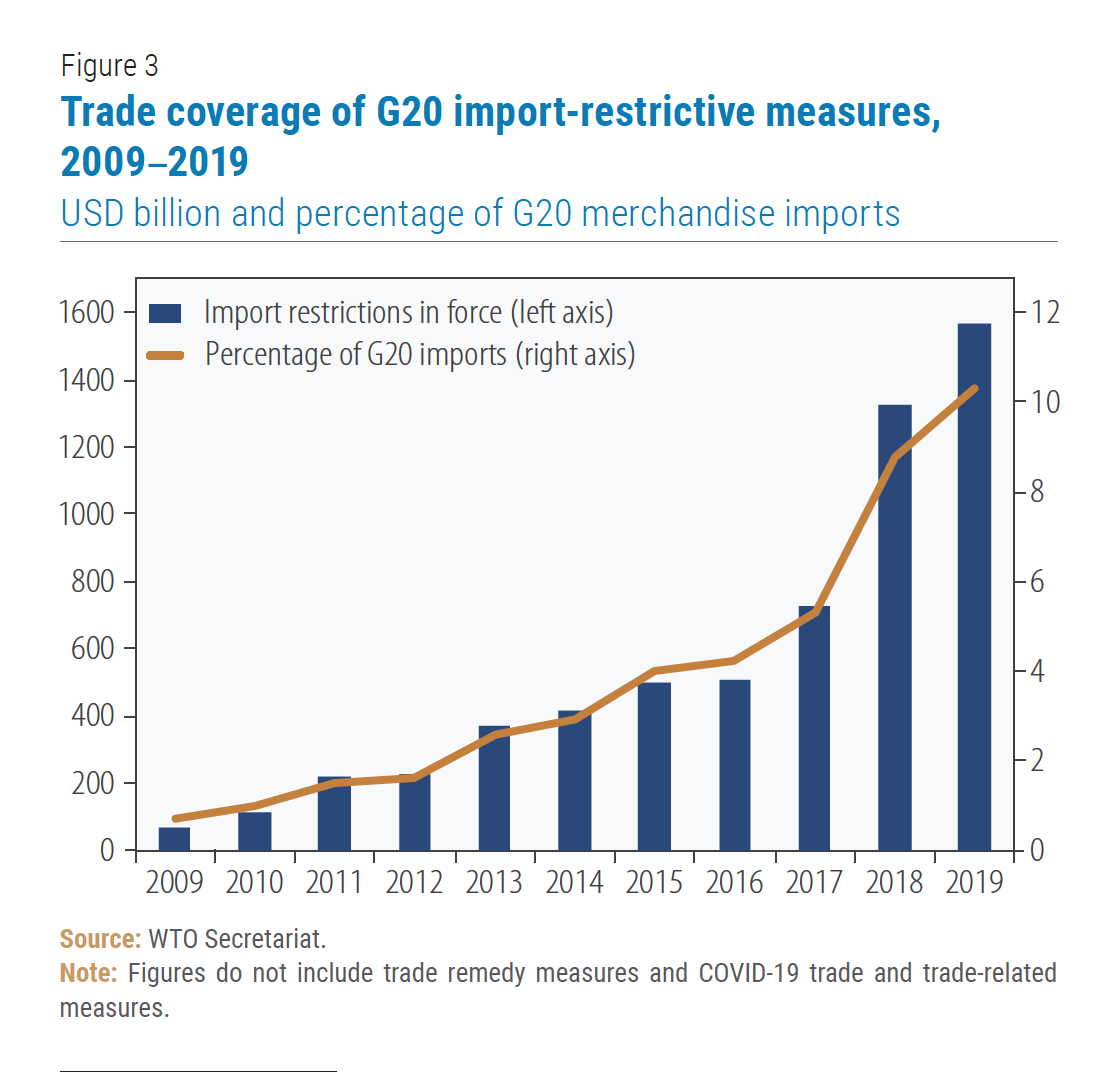

While the current trade woes of developing economies are highly connected to current demand-side weakness related to the outbreak, the constraints to trade faced by these economies are also the result of more systemic issues. Developing countries? trade growth has been declining since well before the pandemic, in 2018 and 2019. These economies have been facing trade restrictions from before the outbreak, such as tariff increases, import bans, stricter customs procedures, among other measures. The levels of import-restrictive measures in the G20, the main trading partners of developing countries, unrelated to the pandemic have soared since May 2018, in terms of trade coverage, and remain historically high (figure 3). These measures collectively affect an estimated 10.3 per cent of G20 imports (worth nearly $1.6 trillion) and continue to grow. The import-restrictive measures implemented between October 2019 and May 2020 alone cover about 2.8 per cent of trade in G20 countries. Currently, no specific commitments have been agreed by the G20 to ease the restrictions.

While the current trade woes of developing economies are highly connected to current demand-side weakness related to the outbreak, the constraints to trade faced by these economies are also the result of more systemic issues. Developing countries? trade growth has been declining since well before the pandemic, in 2018 and 2019. These economies have been facing trade restrictions from before the outbreak, such as tariff increases, import bans, stricter customs procedures, among other measures. The levels of import-restrictive measures in the G20, the main trading partners of developing countries, unrelated to the pandemic have soared since May 2018, in terms of trade coverage, and remain historically high (figure 3). These measures collectively affect an estimated 10.3 per cent of G20 imports (worth nearly $1.6 trillion) and continue to grow. The import-restrictive measures implemented between October 2019 and May 2020 alone cover about 2.8 per cent of trade in G20 countries. Currently, no specific commitments have been agreed by the G20 to ease the restrictions.

The pandemic has further increased the constraints to trade and intensified protectionist tendencies. In a race to safeguard health systems and vital supplies, the pandemic prompted a host of new trade measures. Between 16 October 2019 and 15 May 2020, 60 per cent of new trade and trade-related measures implemented by the G20 economies were linked to the pandemic. Of these, 30 per cent restricted trade, comprising mostly export bans on medical products, including ventilators, surgical masks, gloves, medicine and disinfectant, but also food export restrictions to shield domestic food markets. Proliferation of the latter could negatively affect the food security of import-dependent economies, including in the least developed countries (LDCs). Furthermore, several countries added more detailed screening and/or restrictions on investments in health, medical research, biotechnology and essential infrastructure for the duration of the pandemic. By mid-May, though barriers to imports of pandemic-related products were lowered, only about a third of the trade restrictions had been repealed. Under exceptions, granted by the WTO and many regional trade agreements to protect human life and health and national security, further trade and investment restrictions may be put in place.

The pandemic has also disrupted global value chains (GVCs) across the developing world. Domestic restrictions on which industries are considered ?essential? in order to remain open during COVID-19 lockdowns and which ones are not have resulted in significant regional supply chain disruptions. Pressure to supply domestic markets over international markets has also stoked tensions in some countries (e.g., in Mexico).

Prolonged subdued trade has implications for economic development of export-dependent countries

Last year, merchandise trade volume in the world and in developing countries excluding China contracted for the first time since the global financial crisis of 2008?09 (-0.1 per cent and -1 per cent, respectively). Trade in commercial services increased (2.1 per cent), but the pace of growth decreased sharply from the pace in 2018 (8.4 per cent and 10.1 per cent, respectively). World trade was weighed down by heightened trade tensions as well as by lower global GDP growth, which slowed to 2.6 per cent in 2019 from 3.1 per cent in 2018.

More generally, in recent years, amid a slowing pace of trade liberalization and rising protectionist measures, trade growth has trended downwards significantly. In the two decades prior to the global financial crisis, the average annual growth rate of the volume of world trade was about 7 per cent, but it slowed down to below 3 per cent on average between 2012 and 2019. Trade volume growth in developing countries excluding China was about 6 per cent in the early 2000s, but slowed down to 2 per cent on average between 2012 and 2019.

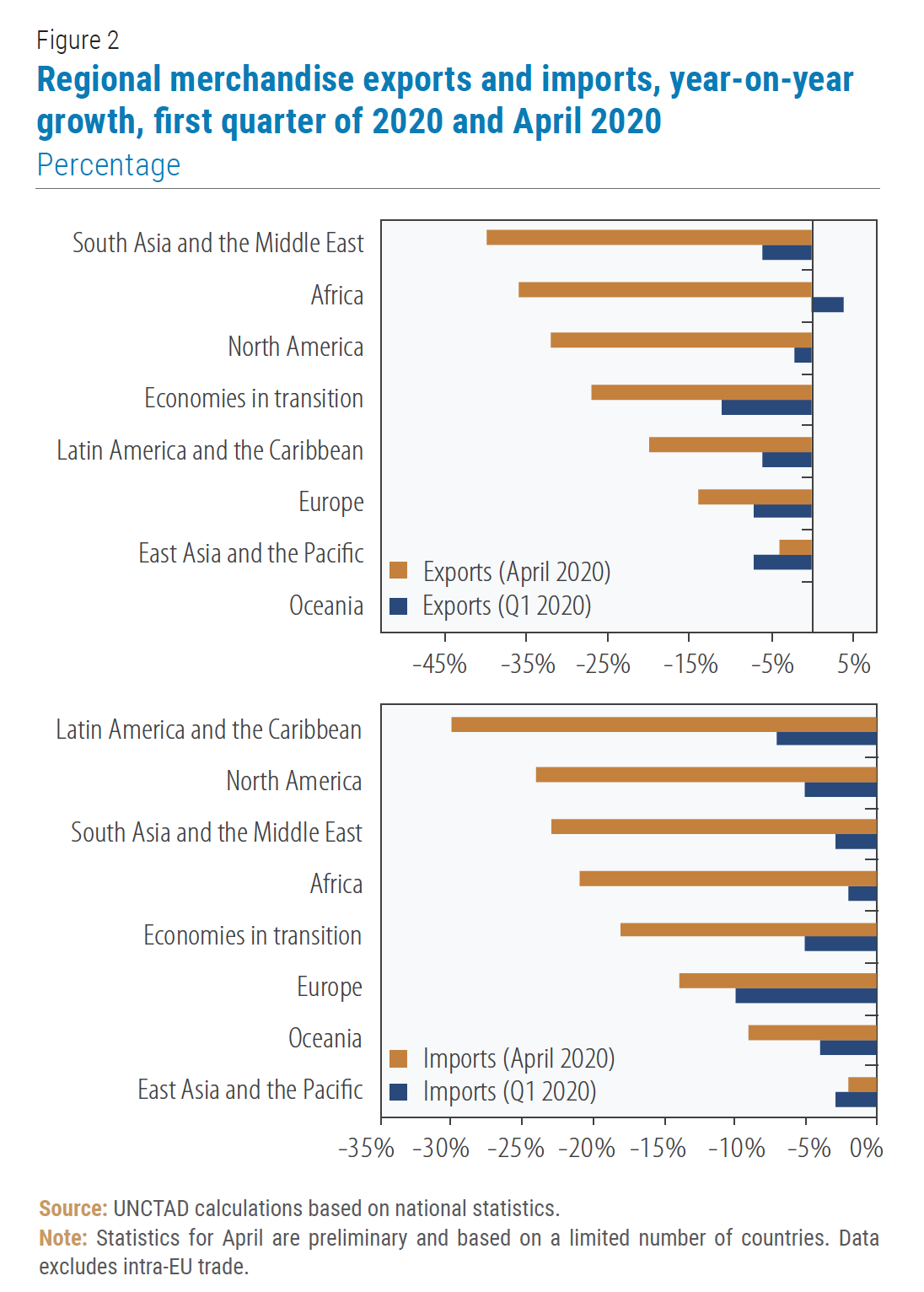

A prolonged subdued global trade environment has significant implications for economic development, especially for exportdependent countries, not least since it adversely impacts investment and innovation decisions. The linkage between trade and investment in developing economies is reflected in the strong positive correlation between gross fixed capital formation and imports (figure 4). From a firm perspective, making the choice of entering or expanding operations in foreign markets is tied to investment, technology adoption and R&D decisions. For instance, in Argentina, trade integration was shown to stimulate the adoption of new technologies and technology upgrades due to higher revenues. Moreover, given the interaction of trade and investment dynamics, subdued trade could likely constrain productivity growth. At the firm level, productivity growth is an endogenous outcome of a number of choices, which are taken jointly with trade participation. Looking ahead, an even more protectionist stance in the international trade environment would hamper the path to revitalizing trade flows, investment and productivity growth.

Regional integration can provide avenues for promoting export activity and diversification

The pandemic has reinforced pre-existing economic trends, namely those of declining productive, commercial and technological interdependence between the main world economies, and less open

world trade, as well as the increasing importance of geopolitical and national security considerations and weakened multilateral decision making. Hence, the global environment poses mounting threats to successful trade-led growth.

Facing an increasingly uncertain world economy, a policy option that is gaining track among developing countries is strengthened regional integration. In Africa, for instance, the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) will soon be launched, creating the largest free trade area in the world that will unite 1.2 billion people with a combined GDP of about $2.2 trillion. One objective of regional integration would be to help shield economies from supply and demand volatility from outside the region. At the same time, it would provide vast markets that can generate economies of scale, especially in strategic industries, such as pharmaceuticals, medical production and research, and agro-processing. This would decrease vulnerability to interruptions of supply as those that occurred during the pandemic, for example regarding personal protective equipment, medical equipment and staple food commodities. Uniting under a larger regional block would also strengthen each country?s ability to negotiate with large economies.

Finally, regional integration can promote export growth as well as diversification. In Africa, lower trade costs are associated with larger exporting firms and higher rates of survival in foreign markets, and, for landlocked countries, could increase their ability to export to more markets. Export diversification is crucial since the impacts from prolonged weak trade growth will be harder on those economies dependent on exports of a narrow range of products to a limited number of markets. Importantly, diversification goes hand in hand with the strengthening of productive capacities. In Africa, more diversified exports have been shown to be dependent on higher productive capacities. A goal of the AfCFTA is the acceleration of industrial development and, in this way, the reconfiguration of African supply chains, the establishment of regional value chains and the manufacturing of essential value added products.

This policy option becomes all the more relevant in a context of possible retrenchment or reconfiguration of GVCs, brought about by escalating trade conflict among major economies, exacerbated in turn by the pandemic and concerns around self sufficiency. The share of GVC trade in world trade expanded significantly in the 1990s and early 2000s, but appears to have stagnated or even decreased in the last decade. However, last year, GVCs still accounted for almost half of all international trade. In the current context, it is unclear how GVCs will or will not change when the risks posed by the virus recede. It could be that few major changes will occur, apart from modifications in industries related to healthcare, since the economic fundamentals for most GVCs still hold. It could also happen that more frequent crises?natural, such as pandemics and natural disasters, or more man-made?lead to a reassessment of the costs and benefits of GVCs. In this case, it could lead to higher supplier diversification (and higher digitalization as a way to deal with complex supply chain management) or it could lead to shortening of supply chains, production re-shoring and holding of more inventories. Whichever the case, the world?s geopolitical conditions and the incentives put in place by governments will sway firms? operational location decisions.

For all these reasons, regional economic cooperation could increasingly shape trade in the future, as it becomes a more important component in developing countries? paths to export growth and economic recovery.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations