Understanding households’ inflation expectations: the role of food and energy prices

Understanding households’ inflation expectations: the role of food and energy prices

Inflation expectations are crucial to economic performance as they influence the effectiveness of both fiscal and monetary policies. Household inflation expectations are particularly important, as they impact decisions on spending, borrowing, and investing. However, discussions about inflation expectations typically focus on market participants and professional forecasters due to the availability of high-frequency data across many countries. In addition, households generally hold significantly higher inflation expectations than financial market participants and professional forecasters. This discrepancy highlights the importance of understanding the factors influencing households’ inflation expectations.

In the post-pandemic period, households’ inflation expectations surged significantly while consumer sentiment deteriorated. Although expectations have since declined from record highs alongside actual inflation, they have recently worsened even as central banks have worked to bring inflation closer to target levels. In the United States, near-term inflation expectations surged significantly during the first quarter, amid rising trade policy uncertainty. In the United Kingdom, expectations have trended upward since last year, while in the Euro Area they have eased in recent months but remain well above actual inflation (figure 1). Surveys show that households continue to expect higher near-term inflation than current averages indicate. This broad-based pattern is evident across both advanced and developing economies—including India, South Africa, among others.

In the post-pandemic period, households’ inflation expectations surged significantly while consumer sentiment deteriorated. Although expectations have since declined from record highs alongside actual inflation, they have recently worsened even as central banks have worked to bring inflation closer to target levels. In the United States, near-term inflation expectations surged significantly during the first quarter, amid rising trade policy uncertainty. In the United Kingdom, expectations have trended upward since last year, while in the Euro Area they have eased in recent months but remain well above actual inflation (figure 1). Surveys show that households continue to expect higher near-term inflation than current averages indicate. This broad-based pattern is evident across both advanced and developing economies—including India, South Africa, among others.

Higher household inflation expectations pose a challenge for central banks, heightening the pressure to communicate policies and achievements clearly. Monetary policy and central bank communication are central to anchoring inflation expectations and limiting the persistence of inflation shocks. Forward guidance and transparent communication of policy objectives (e.g., inflation targets), can significantly influence how households and firms form their inflation expectations.

Determinants of inflation expectations

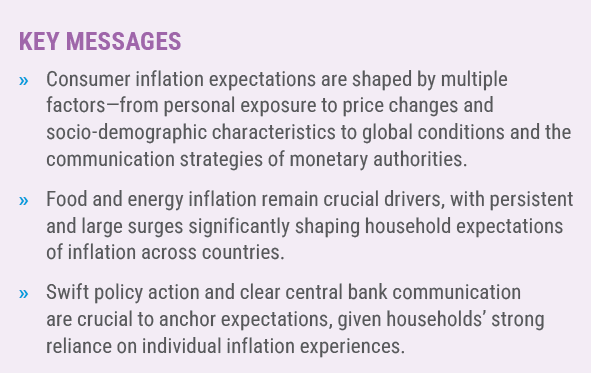

Beyond monetary policy, several socio-demographic and behavioral factors shape how households form inflation expectations. Income, education, age and gender play a particularly important role. Recent research shows that older individuals tend to form their inflation expectations based on past high-inflation episodes, recalling these selectively (Gennaioli et al., 2024). As a result, their expectations tend to be higher and more stable than those of younger cohorts, who adjust more quickly to short-term price changes (figure 2a). Older adults, particularly retirees, typically respond to inflation shocks through changes in saving and withdrawal behavior rather than labor supply or investment decisions, reflecting their reliance on fixed income and limited ability to increase earnings.

Other socio-demographic characteristics such as income, education level and gender may also impact the formation of consumer inflation expectations. Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic indicates that lower-income and less-educated households not only faced higher actual inflation but also anticipated higher future inflation than better-off households (D’Acunto et al., 2022).

Gender differences also influence inflation expectations. Survey data from the US and other developed economies show that women consistently report higher expected inflation than men (figure 2b). Recent studies suggest that the primary explanation lies in traditional gender roles rather than inherent differences in economic reasoning. Women, who more often bear responsibility for household grocery shopping, are exposed more frequently to volatile and salient price changes—particularly noticeable price increases—leading them to expect higher future inflation (D’Acunto et al., 2020). Notably, studies show that this gap narrows when grocery-shopping responsibilities are shared more equally. Beyond household roles, financial confidence also matters: individuals with higher confidence tend to engage more with economic views and form more accurate inflation expectations (Reiche, 2024). Conversely, those with lower financial confidence—who rely more heavily on personal and salient price experiences, such as grocery prices—may develop systematically higher inflation expectations.

Several studies reveal that, beyond standard socio-economic determinants—such as income, age, and education—psychological factors also play a role in shaping inflation expectations. Households and individuals under financial strain or pessimistic about their future income tend to systematically overestimate inflation (Ehrmann et al., 2015). This bias is particularly pronounced during economic downturns and periods of intense media coverage, as news outlets often emphasize high-profile price increases, thereby amplifying perceived inflation risks.

Several studies reveal that, beyond standard socio-economic determinants—such as income, age, and education—psychological factors also play a role in shaping inflation expectations. Households and individuals under financial strain or pessimistic about their future income tend to systematically overestimate inflation (Ehrmann et al., 2015). This bias is particularly pronounced during economic downturns and periods of intense media coverage, as news outlets often emphasize high-profile price increases, thereby amplifying perceived inflation risks.

Expectations also vary geographically. Individuals in the same region often share similar experiences of local price dynamics and labour market conditions. For instance, areas with stronger economies may see more stable expectations, while regions facing persistent unemployment or structural weaknesses tend to display upward-biased expectations. Evidence from U.S. states illustrates how local economic structures contribute to significant heterogeneity in inflation rates and consumer sentiment (Hajdini et al., 2022).

Finally, global factors— such as commodity prices shocks, financial market fluctuations, and exchange rate volatility—further affect inflation expectations. Commodity price shocks, especially in energy and food, and financial market fluctuations can quickly transmit across borders, shaping expectations unevenly. Because food and energy make up a larger share of household budgets in developing economies, such shocks have a stronger effect on inflation perceptions there than in advanced economies (Kose et al., 2019). Moreover, instability in the foreign exchange market often heightens expectations of currency depreciation, which in turn contributes to rising consumer inflation expectations as imported goods become more expensive—particularly in countries where inflation expectations are not well anchored. Conversely, in countries with strong central bank credibility and firmly anchored medium-term inflation expectations, the effects of exchange rate fluctuations are generally limited.

Role of food and energy prices in shaping household inflation expectations

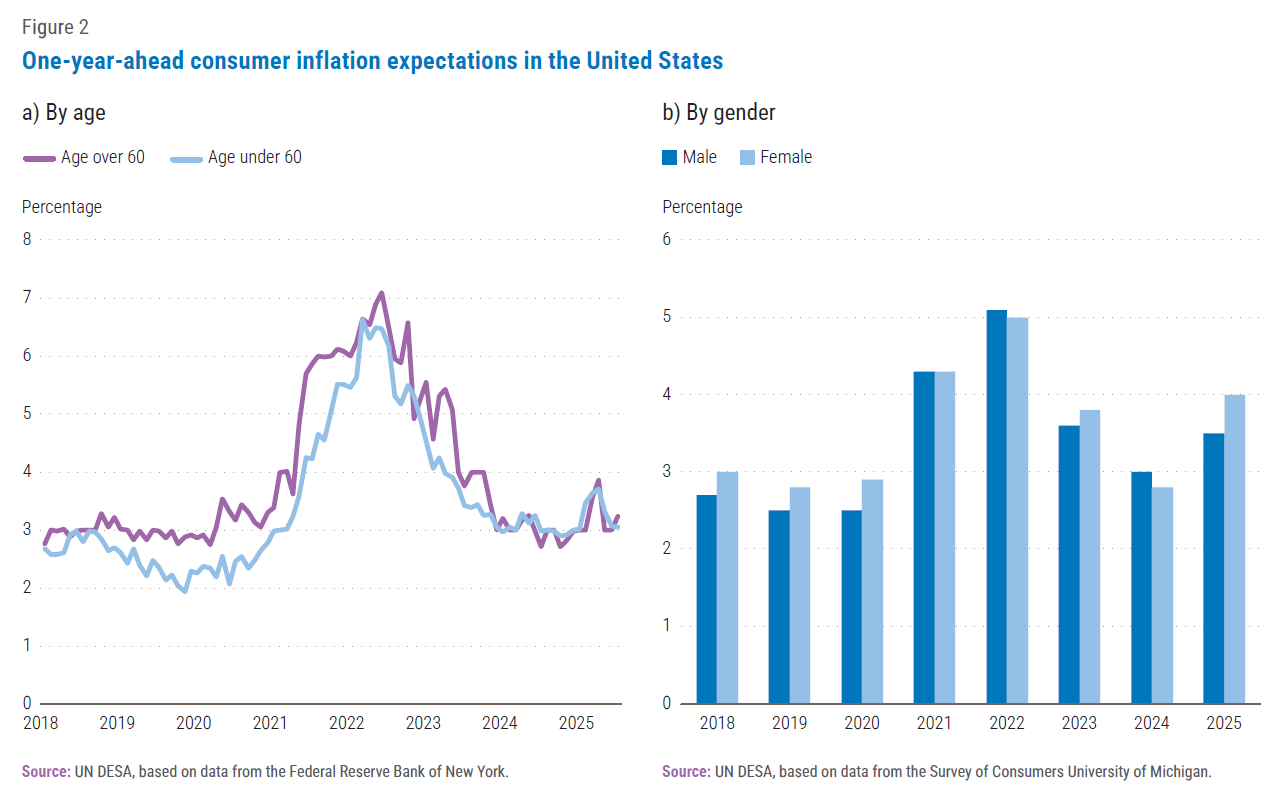

Between 2021–2023, many economies experienced a sharp increase in inflation, driven by rising food and energy commodity prices, supply-side disruptions, and domestic factors (figure 3). On average, food inflation outpaced overall inflation and remained elevated in many countries. Rising food prices have had a particularly significant impact in developing economies, where food accounts for a large share of housing spending. Similarly, energy prices rose significantly, with variation across countries owing to multiple factors including the energy dependence and the elasticity of energy inputs respect to the underlying supply shock.

Although recent research on the role of food and energy prices in shaping both perceived and expected inflation is growing, it remains relatively limited. Studies highlight that consumer inflation expectations are especially sensitive to changes in prices of frequently purchased goods, particularly essential items such food and energy, with notable persistence when individuals attribute a central role to these items in forming their inflation expectations. For example, consumers exposed to large swings in grocery prices are more likely to extrapolate these changes to overall inflation (Weber et al., 2022), helping explain why inflation expectations often exceed and fluctuate more than official measures.

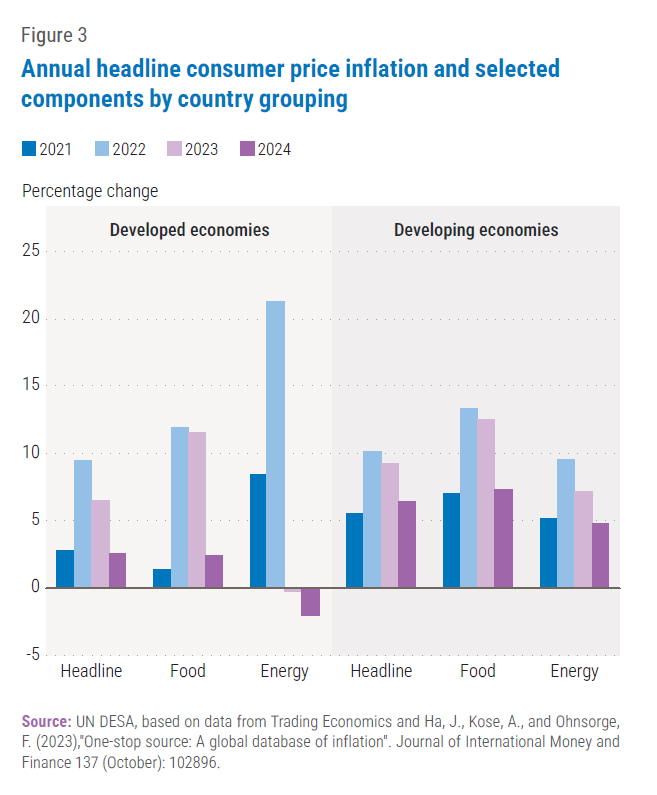

Moreover, household inflation expectations tend to be positively correlated with food inflation and contribute to persistent inflationary trends during high-inflation periods, such as the 2021-2023 episode (figure 4). Empirical evidence shows that household inflation expectations across different horizons are particularly responsive to fluctuations in food inflation, more so than to other components such as energy. Households tend to react strongly to inflation driven by food prices, especially following substantial increases. In addition, the impact of food price shocks on these expectations is not only more pronounced but also notably persistent, indicating that such shocks leave a lasting impression on household expectations. This response is asymmetric; consumers perceived price increases as more lasting and significant than price declines (Anesti et al., 2025). Such biases anchor expectations to recent experiences of rising prices, particularly for essential goods, amplifying their impact on confidence and spending. Moreover, the evidence suggests that household inflation expectations are most likely to become elevated and contribute to persistent inflationary dynamics in response to large and sustained food inflation shocks. This continuous focus on salient essentials helps explain why expectations often overshoot broad inflation measures.

Moreover, household inflation expectations tend to be positively correlated with food inflation and contribute to persistent inflationary trends during high-inflation periods, such as the 2021-2023 episode (figure 4). Empirical evidence shows that household inflation expectations across different horizons are particularly responsive to fluctuations in food inflation, more so than to other components such as energy. Households tend to react strongly to inflation driven by food prices, especially following substantial increases. In addition, the impact of food price shocks on these expectations is not only more pronounced but also notably persistent, indicating that such shocks leave a lasting impression on household expectations. This response is asymmetric; consumers perceived price increases as more lasting and significant than price declines (Anesti et al., 2025). Such biases anchor expectations to recent experiences of rising prices, particularly for essential goods, amplifying their impact on confidence and spending. Moreover, the evidence suggests that household inflation expectations are most likely to become elevated and contribute to persistent inflationary dynamics in response to large and sustained food inflation shocks. This continuous focus on salient essentials helps explain why expectations often overshoot broad inflation measures.

Implications of food and energy price dynamics for monetary policy

Since food and energy prices play such an outsized role in shaping household inflation expectations, monetary policy responses need to account for these dynamics. This raises important questions about how central banks should react to food- and energy-driven shocks, which are often supply-related and temporary, but highly salient to consumers. At the same time, communication strategies may need to explicitly highlight progress on these specific prices to maintain credibility and prevent expectations to drift away from targets.

As household expectations are significantly influenced by personal experiences, swift and decisive policy responses are crucial to lowering actual inflation and reducing the risk of de-anchoring. Central banks need to carefully assess whether food price shocks require a differentiated policy approach compared to other sources of inflation. Monitoring food price developments, rather than solely core inflation, can provide better insights on the persistence of inflation expectations (Bonciani et al., 2024), particularly in countries where the food component represents a large share in the consumption basket. Ultimately, the prominence of food and energy prices in shaping consumer expectations means that central banks cannot rely solely on core inflation measures to guide communication or policy. Tailoring responses to these salient components—while maintaining credibility and transparency—can help stabilize expectations, particularly in economies where food and energy dominate household budgets.

Central bank communication is also key to anchoring inflation expectations. Clear forward guidance, transparent inflation targets, and a consistent policy tone can help anchor expectations and sustain credibility. Moreover, evidence shows that clear and consistent communication during high-inflation periods reassures the public and lowers medium-term inflation expectations (De Fiore et al., 2024). Broader efforts to promote financial literacy and highlight policy achievements also strengthen anchoring. Strong institutional frameworks, independence, and accountability enhance trust in monetary authorities, reducing inflation persistence and stabilizing expectations.

Welcome to the United Nations

Welcome to the United Nations